Deontologists Shouldn't Vote*

By Richard Y Chappell🔸 @ 2025-06-12T20:52 (+10)

This is a linkpost to https://www.goodthoughts.blog/p/deontologists-shouldnt-vote

* (Unless, of course, their vote would help to prevent an even worse outcome.)

In ‘The Curse of Deontology’, I introduced the distinction between “quiet” and “robust” deontology, and referred to my paper refuting the latter. The upshot: deontologists are stuck with the “quiet” view on which no-one can want anyone else to follow it. (Think of it as consequentialism modified by an overriding constraint against getting your own hands dirty. Crucially, you have no reason to want others to prioritize their clean hands over others’ lives.) Quiet deontologists want the consequentialist outcome, they just don’t want to dirty their hands in pursuit of it.

A striking implication of this view is that deontologists should refrain from publicly disparaging consequentialism or trying to prevent others from acting in consequentialist-approved ways. (They may be constrained against lying or positively assisting in wrongdoing, but there’s no general obligation to speak up in harmful ways. Compare Kantians on lying to inquiring murderers vs refusing to answer.) In this post, I’ll step through some examples of this principle in action.

Voting on Trolleys

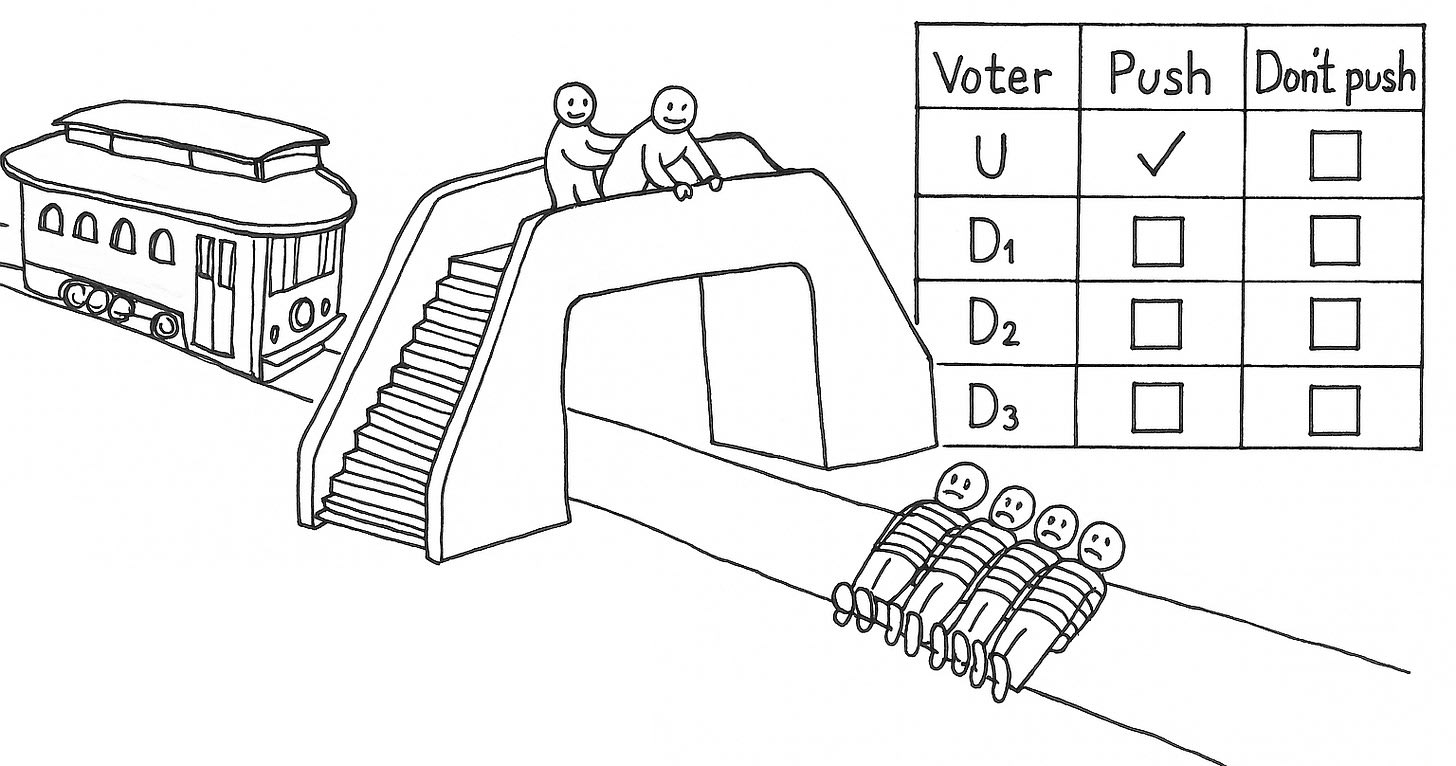

Consider Voting Footbridge: a trolley will kill five, unless a robot pushes a fat man in front of the trolley to stop it first. The robot is controlled by the majority vote of a group of onlookers consisting of one utilitarian and several quiet deontologists. What should the deontologists do (by their own lights)?

Abstain, presumably. Voting to push might make them complicit, and they care about their clean hands more than anything else in the world. But they have no reason to vote against the robot pushing. They want the robot to push! (That’s what makes them quiet rather than robust deontologists.) So they should abstain, and let the utilitarian’s vote carry the day and “wrongly”—but heroically—save the five for them.

After all, there’s no general obligation to vote. We may be obliged to bring about vastly better outcomes, including via voting when our doing so would have that effect. But the sheer act of voting, e.g. on trivialities, is hardly mandatory as such. Moreover, deontologists are generally fine with allowing people to refrain from doing even very good things (like donating to effective charities). So they surely can’t demand that people go out of their way to make things worse. (That would be an insane demand.) So, in particular, there’s no obligation to wrestle the utilitarian for control of the robot. Just sip your tea and leave it be.[1]

Bioethics and Public Policy

This point generalizes in ways that are extremely practically significant. Public policy is routinely distorted by moral idiocy. A vast number of mutually-beneficial exchanges—from life-saving kidney markets to poverty-relieving guest-worker programs—are opposed by utopian enemies of the better who sacrifice individuals for symbolism and consider themselves “moral” for doing it. Research prudes oppose monetary incentives to participate in socially valuable clinical trials. Right-wing propertarians don’t even want to see other rich people taxed for the greater good, nor artistic works made more broadly accessible without the permission of the copyright “owner”. Everywhere, we see people urging each other to be selfish.

None of this makes the slightest bit of sense if “quiet deontology” is correct, because other people doing the consequentialist thing doesn’t dirty your hands.

Again: quiet deontologists want the best outcome to happen, they just don’t want to be personally responsible for it. So, let’s say it again: sip your tea and leave it be. Stop publicly arguing that good things would be “exploitative” or “wrong”. Even if it’s true, you shouldn’t want others to believe that. You should want them to do the thing that results in a better future. (Who cares if they act wrongly? Not quiet deontologists!) So, sip your tea. Let the consequentialist ethicists own the public sphere. If you’re tapped to join the President’s Council on Bioethics? Decline it and recommend Peter Singer as someone better qualified for the role. (Deontology disqualifies you, because it makes you not want other people to do the right thing. Consequentialists, by contrast, can happily take on roles as public moral advisers without compromising their integrity.)

Isn’t this all terribly odd?

Personally, I think principled deontologists should repudiate the “quiet” view and go all-in on trying to find a way to rescue the robust view from my new paradox! But most ethicists evidently disagree. With the honorable exceptions of Jake Zuehl and Andrew Moon, I think every deontologist who has offered feedback on my paper so far (including every critical referee across several journals) ended up endorsing the quiet view. One top journal went so far as to reject the paper as “uninteresting” because they thought it was so obvious that all contemporary deontologists embraced the quiet view. They thought I was targeting a straw man by discussing the robust view at all!

If that sociological claim is correct, then contemporary deontologists should be just as horrified as I am by the role that deontology plays in the public sphere, obstructing beneficial policies for “moral” reasons that are fundamentally anti-social or contrary to the social good. Again, they may think it would be “wrong” for policy-makers to implement the consequentialist policy, or for others to vote for it. But they should hope to see it happen nonetheless. And so they should at least refrain from acting as an obstacle themselves.

Now, if my paradox of robust deontology is successful, everyone (with no personal interests at stake) must prefer to see consequentialist public policies implemented.[2] If your scruples don’t allow you to participate in the implementation, you should—by your own lights—move aside so that others bring about the future that you agree is morally preferable. This may include educating the public—and professional “bioethicists”—to be more consequentialist, so they don’t put political pressure on policymakers to do awful things like prohibiting kidney markets, euthanasia, embryonic selection, or vaccine challenge trials.

I look forward to seeing how prominent deontologists grapple with this challenge: Why (when you have no personal interests at stake) would you try to get other people to act in ways that make the world worse?

- ^

Popular civic ideology pretends that citizens—and especially non-voters—are automatically “complicit” in whatever their government does. Reflection on Voting Footbridge should suffice to reveal this claim as baseless. For further discussion, see my response to Arnold in Questioning Beneficence.

- ^

Technically, this still leaves open how you assess outcomes as better or worse—you needn’t accept the utilitarian’s axiology in particular. All that’s being ruled out here is concern specifically for others violating constraints or acting wrongly. You could, for example, endorse a consequentialism of rights that sought to impartially minimize rights violations. But I’m not aware of anyone who seriously defends such a view. So I assume most would end up endorsing an axiology that’s at least sufficiently similar to utilitarianism as to agree on the sorts of policy issues mentioned in this post.

Guive @ 2025-06-13T03:13 (+7)

This is an article about moral philosophy, not the internal dynamics of the EA community, and it therefore does not belong on the "community" tab.

Sarah Cheng @ 2025-06-13T05:18 (+4)

Seems right, thanks! I've moved it.

SummaryBot @ 2025-06-13T18:13 (+1)

Executive summary: This exploratory post argues that “quiet” deontologists—those who personally avoid causing harm but want good outcomes overall—should not try to prevent others from acting consequentially, including by voting or influencing public policy, and should instead step aside so that better outcomes can be achieved by consequentialists.

Key points:

- Quiet vs. robust deontology: The author reaffirms that “quiet” deontology permits personal moral scruples but offers no reason to oppose others’ consequentialist actions, unlike “robust” deontology which would seek universal adherence to deontological rules.

- Voting thought experiment: In a trolley scenario where a robot pushes based on majority vote, quiet deontologists should abstain from voting rather than stop the consequentialist from saving lives—they want the good outcome but won’t get their own hands dirty.

- Policy implications: Quiet deontologists should not obstruct or criticize consequentialist-friendly policies (e.g. kidney markets, challenge trials) because others’ morally “wrong” actions don’t implicate them and achieve better outcomes.

- Moral advice roles: Deontologists should avoid public ethical advisory roles (like on bioethics councils) if they oppose promoting beneficial policies; they should recommend consequentialists instead.

- Sociological claim: Most academic deontologists already accept the quiet view, which implies they should be disturbed by the real-world harm caused by deontological arguments used in policy.

- Call to reflection: The author challenges deontologists to explain why, if they privately hope for better outcomes, they act to prevent others from bringing those outcomes about.

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.