How accurately does anyone know the global distribution of income?

By Robert_Wiblin @ 2017-04-06T04:49 (+22)

Cross posted from the 80,000 Hours blog.

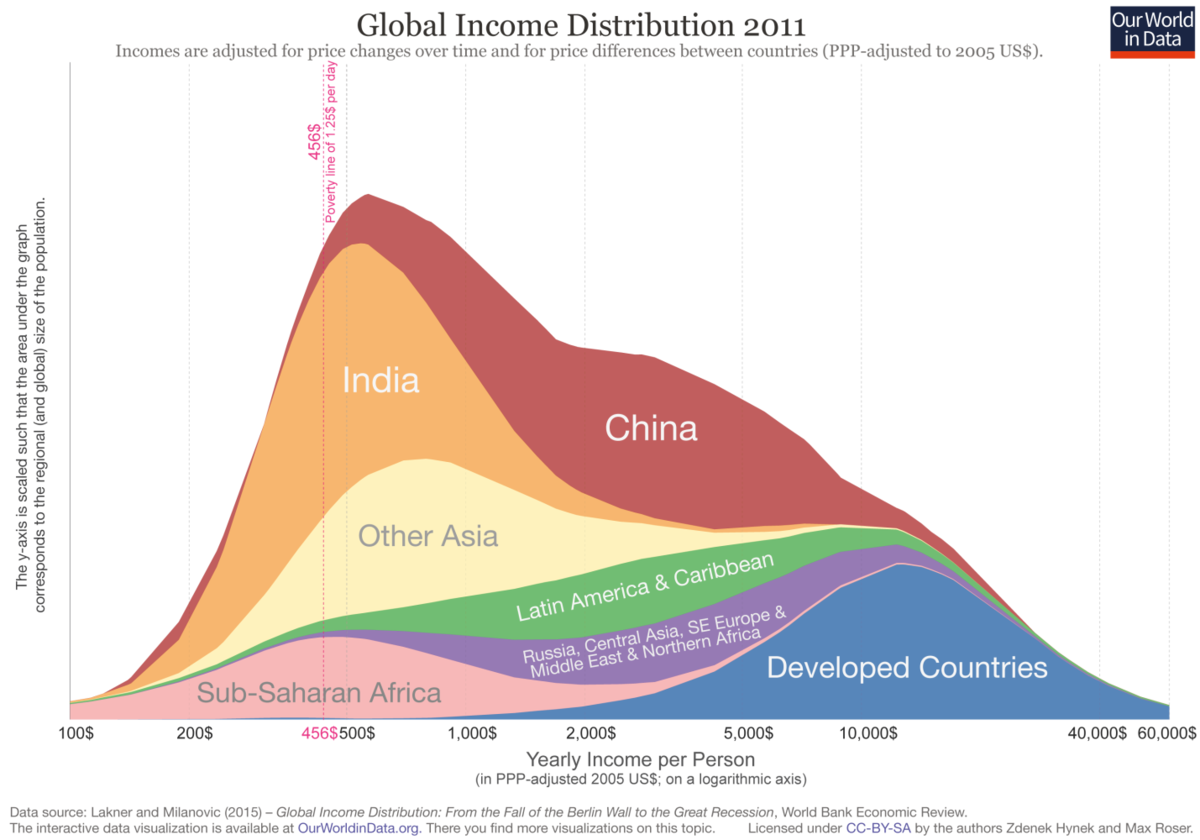

How much should you believe the numbers in charts like this?

People in the effective altruism community often refer to the global income distribution to make various points:

- The richest people in the world are many times richer than the poor.

- People earning professional salaries in countries like the US are usually in the top 5% of global earnings and fairly often in the top 1%. This gives them a disproportionate ability to improve the world.

- Many people in the world live in serious absolute poverty, surviving on as little as one hundredth the income of the upper-middle class in the US.

Measuring the global income distribution is very difficult and experts who attempt to do so end up with different results. However, these core points are supported by every attempt to measure the global income distribution that we’ve seen so far.

The rest of this post will discuss the global income distribution data we've referred to, the uncertainty inherent in that data, and why we believe our bottom lines hold up anyway.

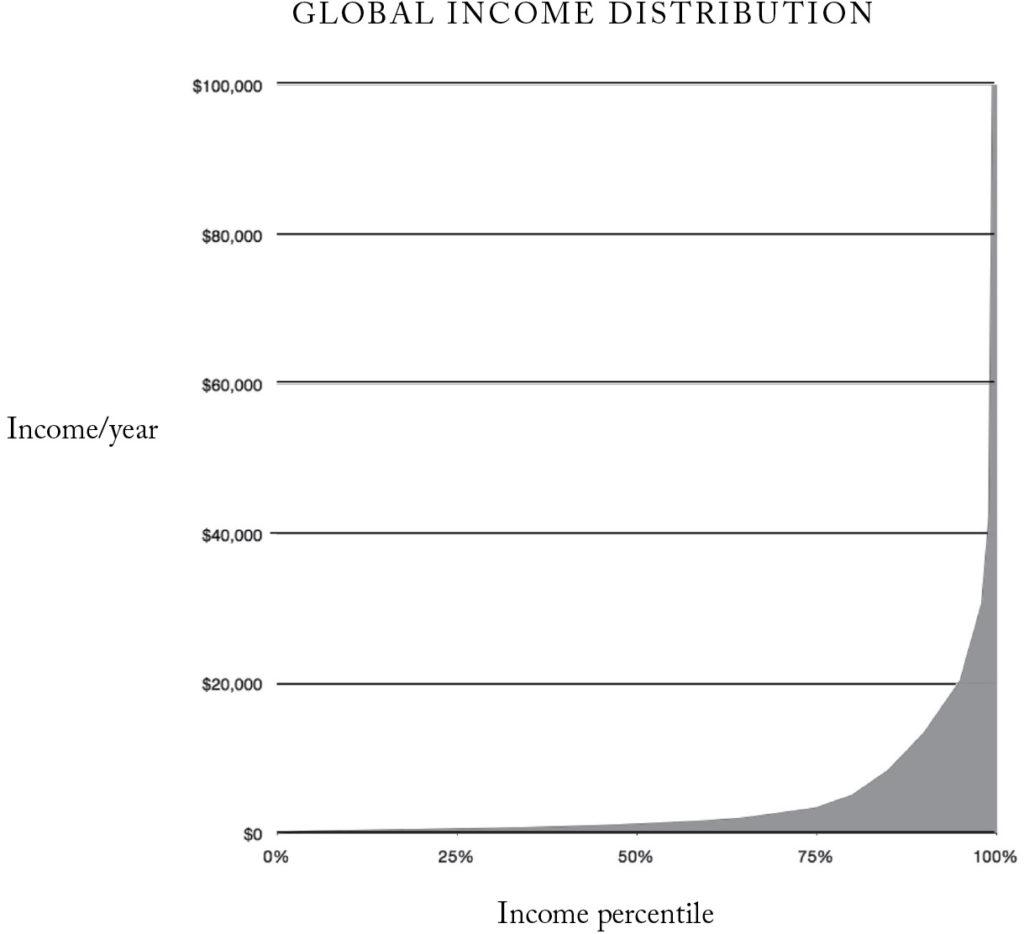

Will MacAskill had a striking illustration of global individual income distribution in his book Doing Good Better, that has ended up in many other articles online, including our own career guide:

The data in this graph was put together back in 2012 using an approach suggested by Branko Milanovic, at the time lead economist in the World Bank's research department, and author of The Haves and the Have-Nots. Incidentally, Milanovic went on to achieve mainstream fame for the so-called ‘elephant graph’. For the bottom 80% of the income distribution we used World Bank figures from their database ‘PovcalNet’. As this data set was not considered reliable for the top 20% of the income distribution, we substituted them with figures from Branko Milanovic’s own work compiling national household surveys.

Some have questioned whether the graph gives a misleading picture of global income inequality. How seriously should we take it?

One obvious concern is that this distribution is based on income surveys from 2008, and the global income distribution may have changed since then. Strong economic growth in countries like China has improved the lot of people in the middle of the income distribution, while the Great Recession in 2008-10 suppressed incomes in rich countries more than poor countries. Hellebrandt and Mauro attempts to estimate how the income distribution changed between 2003 and 2013, and finds a quite significant shift.[fn 1]

Why are we still using numbers from 9 years ago? Complete and consistent global income distribution estimates arrive infrequently and at a substantial delay, because they rely on surveys trickling in from over 150 countries around the world, and being made comparable. 2008 is still the last year for which we are aware of publicly available and compatible survey figures across the whole distribution. We are working to get access to newer figures that are not yet public, though they will only bring us up to 2011.

But that’s only the beginning of the difficulties. There are lots of ways different organisations might produce different numbers:

1. The underlying survey data may be inaccurate or sample differently. For example, different polling groups will have different ways of trying to question a representative cross-section of people in a country about their income. Needless to say this gets very challenging. Imagine trying to make sure you’ve fairly sampled the poorest 20% of people in India, or the Democratic Republic of Congo. The people you want to sample may be in rural areas without access to any telecommunications. How do you know you’ve got the right number of people from these groups in your measurements? And how do you measure the equivalent income of people who grow food for their own consumption, rather than receive a salary? PovcalNet is up-front about the serious challenges they face:

More than 2 million randomly sampled households were interviewed in these surveys, representing 96 percent of the population of developing countries. Not all these surveys are comparable in design and sampling methods. Non representative surveys, though useful for some purposes, are excluded from the calculation of international poverty rates. ... No data are ideal. International comparisons of poverty estimates entail both conceptual and practical problems that should be understood by users.

In line with its desire to measure the extent of effective poverty around the world, PovcalNet uses measures of *consumption* where they are available. This means that income people receive which they then save is not counted, while spending funded by past savings *is* counted, and savings this year will appear in future years' consumption. Our World In Data [has more information](https://ourworldindata.org/extreme-poverty/) on how this is done.

If you’d like to learn more about how questionable data coming out of the developing world can be, a good source would be Poor Numbers by Morten Jerven.

Getting enough data about the top 1% of earners is difficult in a different way: they represent only a small fraction of respondents in surveys, their income sources are more varied, and their incomes differ enormously.

2. Different ways of adjusting for ‘purchasing power’. Money goes further in poorer countries, and any sensible attempt to look at global income will account for this. But how do you compare the value of two currencies when the people in the relevant countries are buying very different things? Very few identical products are bought in both rural Kenya and Switzerland, so any attempt to compare the practical purchasing power of Swiss francs and Kenyan shillings is going to be imprecise. Moreover, even within countries people at different parts of the income distribution consume very different bundles of goods, and therefore are affected by different prices. Economists do their best to sample what people are buying in a range of places, how similar their quality is to goods elsewhere, and what they cost - but only so much is possible. In one dramatic case, a revision of purchasing power parity weights by the World Bank in 2005 cut China’s purchasing power parity-adjusted GDP by 40 per cent. Then in 2014 it was revised back up based on surveys conducted in 2011, suddenly making it the largest economy in the world (maybe, anyway).

Finally, how do people deal with the varied cost of living in different places within a country? I’ve never seen these adjustments made. And it’s unclear how much they should be made. One way people choose to spend their income to improve their lives is to live in expensive cities!

3. Different ways of dealing with household size. Sometimes income data is given ‘per capita', and other times it’s given ‘per household’. This can change the shape of an income distribution, because globally larger families have lower incomes. Larger families also have greater ‘economies of scale’ (e.g. they might share a single house or car). When economists want to take household income from surveys and ‘individualise’ the figures to compare across households of different sizes, they use ‘equivalence scales’. But estimates of the right equivalence scales differ a remarkable amount. Using one method, a couple and one child living on $20,000 collectively, have an effective individual income of $15,200. Using a method at the other extreme, the figure is $9,100. You might also just divide total household income by the number of family members and ignore any of the effects of family structure (this is the approach taken in PovcalNet and Milanović's figures). This creates another source of variation in how the survey data is processed before you see it.

4. Different dollar units. Figures for global income comparisons are usually given in ‘international dollars’. Occasionally 1990 international dollars are used for comparison of changes in data over long time periods. Other times you’ll find figures in 2000 international dollars, 2011 international dollars, or whatever year the data were released. Inflation between these different time periods can move the figures by 10-40%.

5. Are the figures after tax or pre-tax? Gallup Polling and Hellebrandt and Mauro (2015) report income pre-tax. The Brankovic figures used above are post-tax. PovcalNet doesn’t say on their site, but in correspondence I’ve been told “in principle the figures are post-tax” (the World Bank is forced to draw on many varied data sources). This alone could create a 25-50% gap between them.

Is pre-tax or post-tax the better way to do things? Reasonable people can disagree about this. People in poorer countries pay less tax, which in a sense boosts their spending power. But they also get fewer services from their governments in return, forcing them to buy them out of pocket. On the other hand, if high income earners in a given country are funding financial transfers to people on lower incomes - rather than services they personally receive - it makes more sense to exclude those taxes from their effective income.

One person sent us figures from Gallup Polling that seemed to dramatically conflict with our graph - a median income of $9,733 vs the $1,272 we pulled out of the World Bank’s PovcalNet. The first big adjustment is that the $10,000 figure is for households, whereas the chart we use gives figures for individuals. The per person income figure from Gallup is the more modest $2,920.

If that person had looked around, they would have found that other sources give different numbers again. For example, Hellebrandt and Mauro, which I mentioned above, offers a global median income of $2,010 in 2013.[fn 2] Milanovic’s estimate was $1,225 for 2005, and $1,480 for 2008.[fn 3]

A substantial fraction of those differences can be explained by rising incomes over time, and the fact that the two higher numbers are pre-tax, and the lower two post-tax. What explains the remainder? The information required to figure that out isn’t publicly available, and answering that question is really a job for an expert in the field rather than a dilettante such as myself. One possibility is that the surveys used by the World Bank go further into poor, dangerous and rural communities than those by Gallup (a private polling company). Evidence fo this is that in their income tables Gallup appears to only have surveyed the capital city of the Democratic Republic of Congo. In addition, as far as I could see Gallup’s polling data has not yet been published in an economics journal, so there could be quite a few methodological differences with the rest of the literature.

All that said, given the range of choices researchers are required to make, a difference of this size isn't much of a surprise. Political scientist Merle Kling once proposed three ‘iron laws of social science’, and they apply here as much as anywhere:

1. Sometimes it’s this way, and sometimes it’s that way.

2. The data are insufficient.

3. The methodology is flawed.

These figures are approximations. However, having had personal experience with social science data, the rigour here is better than I would have expected going in. As far as I can tell most researchers are making defensible decisions while trying to produce these estimates.

And despite the challenges, these bottom lines remain in every estimate of the global income distribution I’ve seen so far:

- The richest people in the world are many times richer than the poor.

- People earning professional salaries in countries like the US are usually in the top 5% of global earnings and sometimes in the top 1%. This gives them a disproportionate ability to improve the world.

- Many people in the world live in serious absolute poverty, surviving on as little as one hundredth the income of the upper-middle class in the US.

[fn 1] Hellebrandt, Tomas and Mauro, Paolo (2015) – The Future of Worldwide Income Distribution (April 1, 2015). Peterson Institute for International Economics Working Paper No. 15-7. Available at SSRN or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2593894. [/fn]

[fn 2] Incidentally, it’s unlikely they could have had global survey data compiled for 2013 by 2015, as individual country distributions for 2013 are only becoming available now. So they probably used modelling assumptions about growth at different parts of the distribution. The more you know! [/fn]

[fn 3] The former of these is in The Haves and the Have-Nots vignette 3.2. The latter figure is from personal correspondence. [/fn]

undefined @ 2017-04-07T22:34 (+3)

Thanks for this and thanks as always for all the fantastic 80,000 Hours content.

undefined @ 2017-04-08T21:21 (+2)

Thanks for writing this! This is a helpful overview of some of the challenges in coming up with a single quantitative view.

Overall, I think this suggests two things about how to display and interpret the relevant data.

First, when using purely quantitative estimates of distributions in currency terms to illustrate an overall trend, use a variety of different consistent estimates. It seems like when the whole thing you're trying to estimate is income inequality, stitching together different sources for the portions below and above the 80th percentile is very likely to introduce problems. For instance, if your above-80% source is better at detecting income, or otherwise biased upwards relative to your below-80% source, then this will substantially overestimate income inequality.

I would have liked to instead see the whole curve drawn from PovCalNet numbers, with the trendline from Milanovic overlaid on it. Or, ideally, as many different estimated lines as you can measure on the same axis. It's fine to merely footnote or link to explanations for exactly why the lines differ, how they were generated, and your thoughts on which ones are better estimates for which quantiles, but when you use a single graph, people are likely to assume that it's an authoritative illustration of a single data source, whereas showing multiple estimates makes it clearer that there is uncertainty about the details, but not about the fact that the distribution is very unequal.

If you're worried that this would lead to a too-noisy graph, I highly recommend Edward Tufte's books for advice on how to visually display a large amount of quantitative information elegantly.

Second, we shouldn't use these numbers directly to make judgments about specific programs to help poor people. Instead, when trying to evaluate any particular decision, we should make sure we understand how a difference in dollar figures relates to a difference in material conditions, since this will not be perfectly consistent.

For instance, if you use "purchasing power parity" figures, you may get a better estimate of how big differences in material circumstances are, but at the cost of obscuring things like what percentage of someone's income a cash transfer of a certain size will constitute. For this reason, the work charities like GiveDirectly and JPAL are doing directly reporting on what happens as a result of various interventions is extremely important.

undefined @ 2017-04-08T21:47 (+1)

Thanks Ben, this sounds reasonable. I'm working to create a new figure that will have more recent data, inflation adjust up to 2017, and offer more details about precisely how it was constructed. I'll keep these ideas in mind.

Unfortunately, as I'm waiting on other people busy people to get back to me with the data/information I need, I can't say when I'll be able to put it up.

undefined @ 2017-04-08T22:10 (+2)

I'm looking forward to it whenever it's ready.

As an aside, one advantage to Tufte-style information-dense charts is that they can be interesting enough to engage readers with more of the details of the content, and not just say "yeah, OK" to your main point. For instance, the first graph in your post rewards additional attention. When readers engage with the details, they may learn more valuable things from the data than the ones you'd had in mind.

undefined @ 2017-04-07T00:43 (+2)

2 (Different ways of adjusting for ‘purchasing power’) is tough, since not all items will scale the same amount. And markets typically are aimed at specific populations, so rich countries like America often won't even have markets for the poorest people in the world. The implication of this is that living on $2 per day in America is basically impossible, while living on $2 per day, even when "adjusted for purchasing power" in some poorer parts of the world (while still incredibly difficult), is more manageable.

undefined @ 2017-04-06T17:37 (+2)

these bottom lines remain in every estimate of the global income distribution I’ve seen so far... Many people in the world live in serious absolute poverty, surviving on as little as one hundredth the income of the upper-middle class in the US.

But is this bottom line really approximately true?

A salary of $70,000 could be considered upper-middle-class. 1/100th of $70,000 is $700.

According to the chart, that is slightly greater than the income of the median Indian, adjusted for PPP.

Since these figures have been adjusted, that should mean that $700 in Western Europe or the US will afford you the same quality of life as the median Indian person, without you getting any additional resources such as extra meals from sympathetic passers-by or free accommodation in a shelter (because otherwise, to be 100 times richer you would have to have 100 units per day of these additional resources - i.e. $70,000 plus 100 meals/day plus owning low-quality accommodation for 100 people).

However, $700/year (= $1.91/day, =€1.80/day, =£1.53 /day) (without gifts or handouts) is not a sufficient amount of money to be alive in the west. You would be homeless. You would starve to death. In many places, you would die of exposure in the winter without shelter. Clearly, the median person in India is better off than a dead person.

A realistic minimum amount of money to not die in the west is probably $2000-$5000/year, again without gifts or handouts, implying that to be 100 times richer than the average Indian, you have to be earning at least $200,000-$500,000 net of tax (or at least net of that portion of tax which isn't spent on things that benefit you - which at that level is almost all of it, unless you are somehow getting huge amounts of government money spent on you in particular).

The reality is that a PPP conversion factor is trying to represent a nonlinear mapping with a single straight line, and it fails badly at the extremes. But the extremes are exactly where one is getting this (misleading) factor of 100 from.

undefined @ 2017-04-06T19:21 (+9)

I think your last paragraph is plausibly true and relevant, but this is a common argument and it has common rebuttals, one of which I'm going to try and lay out here.

However, $700/year (= $1.91/day, =€1.80/day, =£1.53 /day) (without gifts or handouts) is not a sufficient amount of money to be alive in the west. You would be homeless. You would starve to death. In many places, you would die of exposure in the winter without shelter. Clearly, the median person in India is better off than a dead person.

The basics of survival are food, water, accommodation and medical care. Medical care is normally provided by the state for the poorest in the West so let's set that to one side for a moment. For the rest we set a lot of minimum standards on what is available to buy; you can't get rice below some minimum safety standard even if that very low-quality rice is more analogous to the rice eaten by a poor Indian person, I would guess virtually all (maybe actually all?) dwellings in the US have running water, etc.

This presents difficult problems for making these comparisons, and I think it's part of what Rob is talking about in his point (2). One method that comes to mind is to take your median Indian and find a rich Indian who is 10x richer, then work out how that person compares to poor Americans since (hopefully) the goods they buy have significantly more overlap. Then you might be able to stitch your income distributions together and say something like [poor Indian] = [Rich Indian] / 10 = [Poor American] / 10 = [Rich American] / 100. I have some memory that this is what some of the researchers building these distributions actually do but I can't recall the details offhand; maybe someone more familiar can fill in the blanks.

A realistic minimum amount of money to not die in the west is probably $2000-$5000/year, again without gifts or handouts, implying that to be 100 times richer than the average Indian, you have to be earning at least $200,000-$500,000 net of tax (or at least net of that portion of tax which isn't spent on things that benefit you - which at that level is almost all of it, unless you are somehow getting huge amounts of government money spent on you in particular).

Building on the above, hypothetically suppose over the next 50 years the West continues on its current trend of getting richer and putting more minimum standards in place; the minimum to survive in the West is now $10,000 per year and the now-much-richer countries have a safety net that enables everyone to reach this. However, in India nothing happens.

Is it now true that I need at least $1,000,000 per year to be 100x richer than the median Indian? That seems peverse. Supposing my income started at $100,000 and stayed constant in real terms throughout, why do increases in minimum standards that basically don't affect me (I was already buying higher-than-minimum-quality things) and don't at all affect the median Indian make me much poorer relative to the median Indian? As a result I think this particular section 'proves too much'.

undefined @ 2017-04-11T20:18 (+7)

"However, $700/year (= $1.91/day, =€1.80/day, =£1.53 /day) (without gifts or handouts) is not a sufficient amount of money to be alive in the west. You would be homeless. You would starve to death. In many places, you would die of exposure in the winter without shelter."

One could live on that amount of money per day in the West. You'd live in a second-hand tent, you'd scavenge food from bins (which would count towards your 'expenditure', because we're talking about consumption expenditure, but wouldn't count that much). Your life expectancy would be considerably lower than others in the West, but probably not lower than the 55 years which is the life expectancy in Burkina Faso (as an example comparison, bear in mind that number includes infant mortality). Your life would suck very badly, but you wouldn't die, and it wouldn't be that dissimilar to the lives of the millions of people who live in makeshift slums or shanty towns and scavenge from dumps to make a living. (Such people aren't representative of all extremely poor people, but they are a notable fraction.)

undefined @ 2017-04-12T04:19 (+4)

Hey, a few comments:

But is this bottom line really approximately true?

Rob is saying “in every estimate of the global income distribution I’ve seen so far”, there has been a 100:1 ratio, which is true because this is what's shown by all the official data.

You could, of course, doubt the existing estimates. My general policy is to go with the expert view when it comes to issues that have been thoroughly researched, unless I've looked into it a lot myself. At 80,000 Hours, we don't see ourselves as experts on measuring global income, so instead go with the World Bank, Milanovic and others. Moreover, to our knowledge, the objections raised here are all well understood by the experts on the topic, and have already been factored into the analyses.

That said, here a few comments to show why the Milanovic etc. estimates are not obviously wrong. First, I'll state the problem, then consider the arguments.

I'm claiming that US upper middle class = $100k+ for the reason above. The World Bank estimated 800m people live under $1.9 per day in their 2015 figures, or $600 per year. In reality, many of them will live well below that level. So there's probably hundreds of millions living under $300 per year. This means there's over a factor of 300 difference between "upper middle class" and "large numbers of the global poor"

So, for the claim to be strictly wrong, the consumption of the poor have to be relatively underestimated by a factor of 3. Given the difficulties in making these estimates, this doesn't seem out of the question, but is not obvious.

Moreover, for it to be wrong in a way that becomes decision-relevant, you'd need the understatement to be more like a factor of 10. Even then, it would still be true that upper middle class earn 30x what the global poor earn, so they'd still be able to benefit others at little cost of themselves, and have a disproportionate influence on the world. But, it would be less pressing than a 300x difference.

Here are a couple of reasons why it's not obvious the world bank etc is off by a factor of 10.

It seems the main argument is that you'd die with under $2/day in the west and no hand-outs, so quality of life is worse than $2 in the developing world.

Will gives one response to that in another comment. You wouldn't actually die.

Another point is that it would indeed be harder to live in the west on $2/day, because the low-quality goods that the global poor use are not available to buy. I think the relevant comparison is more like "if there were lots of people living on $2/day in the west, what quality of living would you get?". It's artificial to imagine one person living in extreme poverty without a market and community around them. The PPP adjustments are meant as a hypothetical "what you could buy on $2 per day if the same goods were sold in stores, or if there were lots of other poor people in the country". (Though of course this is one reason why the comparisons are difficult conceptually.)

You've argued that the incomes of the poor are understated, but I think the incomes of the rich are also understated. As an inhabitant of a rich country, you get to consume lots of extra public goods that aren't fully included in the post-tax income figures in these data-sets e.g. safety, clean air, beautiful buildings, being surrounded by lots of educated people. You wouldn't get as many of these in a poor community in a poor country, so this is a way in which the global poor are relatively even worse off than the income comparisons suggest.

Finally, you mention cost of living in another comment as being relevant. Our audience lives in cities where cost of living is higher, making them relatively poorer. However, I think this might be a red herring. Generally, people move to a city to get higher income. If the market is roughly efficient, then the income boost from being in a city should at least offset the increase in cost of living. So it factors out of the equation.

undefined @ 2017-04-26T17:27 (+1)

it would indeed be harder to live in the west on $2/day, because the low-quality goods that the global poor use are not available to buy. I think the relevant comparison is more like "if there were lots of people living on $2/day in the west, what quality of living would you get?". It's artificial to imagine one person living in extreme poverty without a market and community around them.

OK, so maybe appeals to donate money based on factors of 100 wealth difference should be limited to people who actually have a third-world price/quality market for (food, accommodation, shelter) available to them. Hmmmm OK that would be no-one at all.

Then we come to this:

You could, of course, doubt the existing estimates. My general policy is to go with the expert view when it comes to issues that have been thoroughly researched,

...

The PPP adjustments are meant as a hypothetical "what you could buy on $2 per day if the same goods were sold in stores, or if there were lots of other poor people in the country".

So they've thoroughly researched a question which is completely different than the one I care about, which is what I can actually buy and do.

As an inhabitant of a rich country, you get to consume lots of extra public goods that aren't fully included in the post-tax income figures in these data-sets e.g. safety, clean air, beautiful buildings, being surrounded by lots of educated people.

But these things are mostly not worth the massive amount of tax money I have to pay. And that's partly because that tax money is not being spent on me, (I have looked at government spending and the part of the pie that is spent on "things that childless healthy 30 year-olds want" is extremely small.), partly because taxation is progressive so punishes people who earn well, and partly because others in the west have different preferences about how much to spend reducing various risks (such as the risk of a $50,000 car being damaged in a collision with my $1000 old banger).

I would contend that I am not (on $60k) 100 times richer than the average Indian, at least not in the same way that someone on $6M is 100 times richer than me; the way that they really can buy my entire life 90 times over and still be way better off than me.

Anyway, thanks for responding to me, best regards, Jaded.

undefined @ 2017-04-27T05:37 (+1)

OK, so maybe appeals to donate money based on factors of 100 wealth difference should be limited to people who actually have a third-world price/quality market for (food, accommodation, shelter) available to them. Hmmmm OK that would be no-one at all.

I agree that makes sense given one interpretation of the claim. But that definition also has some odd implications. Why does the actual option need to be available to you, even if you're never going to take it?

If a shanty town opens down the road from me, giving me the option to live like the global poor, I become richer relative to my neighbors, but I don't become richer in absolute terms. The reason the super cheap goods the global poor buy don't exist in the West is because no-one wants them. Even if a shanty town opened, I'd buy the same stuff as before, so my quality of life would be exactly the same. Your definition, however, would say I've become ~10x richer, which seems odd.

I think both senses of the term are relevant and interesting. Personally, I find the sense used by the World Bank better at capturing what I intuitively think about when comparing living standards and income. But it's useful to consider both.

You also haven't shown that the differences would amount to a factor of 10. Even though the exact goods the global poor would use are not available in the West, there are still very cheap goods available (as in Will's comment).

But these things are mostly not worth the massive amount of tax money I have to pay.

That's a good point - you're likely a net contributor of taxes right now. But many of things I mentioned aren't a result of taxes. There are lots of public goods produced by being around lots of other educated, wealthy people that you benefit from but aren't captured in the income figures, such as lower crime, more beautiful buildings, more opportunities to talk to people like that, lack of sewage on the street and so on.

Moreover, you're going to get some of those taxes back in the future (and you've benefited from taxes when younger). I think the lifecycle comparison is more relevant.

Over your life, you're probably not net-losing more than 10-20% of your income, so it's not a big factor in the comparison. We're looking for a 10x difference, not a 10% difference.

You can also reclaim tax on donations, so if the message if to donate more, arguably we should use pre-tax income instead.

undefined @ 2017-04-28T08:17 (+1)

If a shanty town opens down the road from me, giving me the option to live like the global poor, I become richer relative to my neighbors, but I don't become richer in absolute terms. Even if a shanty town opened, I'd buy the same stuff as before, so my quality of life would be exactly the same.

I think this is incorrect. Right now I am looking for accommodation. The cheapest option I can find (which doesn't have a working washing machine and is a single small room with shared facilities) costs €5400 per year. It would be very useful for me to have the option to live in a room of quality and price at the level of the 75th or 80th percentile in India. Eyeballing the graph above, the 80th percentile in India is on $1500 or so. They can't be paying more than $700 for their accommodation.

I have to go live in this room - the alternatives are even more expensive, or being homeless and losing my job.

I agree that the shanty town wouldn't help me - I would stink of feces and quickly lose my job on personal hygiene grounds - but the 50th and 75th and 80th percentiles in India do not live in 'shanty towns'. Or am I completely misinformed here?

The reason the super cheap goods the global poor buy don't exist in the West is because no-one wants them.

that's false - they don't exist because the government bans or taxes them, or because of cost disease. In almost every relevant category (cars, accommodation, food, household goods), the government bans you from buying the cheap options.

E.g.

- Bike helmet made in China for $3 but sells for €40. (Compulsory safety testing to ludicrously high standards, tax, overheads)

- Want to buy a second hand toaster? Nope, banned in many countries because it might be hazardous. Pay for a new one, including all the tax and overheads and then when you've finished, throw the old one away.

- Learn to drive in the UK as a new young, male driver)? That'll be £1500 for lessons, plus £3800 for insurance Why? Do people in India or Brazil need to pay that much? You tell me!

- Want to buy a cheap new car like the Tata Nano? Nope, your government has banned it because it's 99.999% safe rather than 99.9999% safe.

- Surely a speeding fine will be inconsequential to someone in the top 1% of the global income distribution, because the harm from speeding on a road is a fixed quantity? No, the government wisely decided to make it it scale with your income!

- want to buy/rent a very small house/flat/room? Nope! It has to have a bunch of amenities and features that you don't need, by law.

- Want to buy a simple product like milk at market price? Nope! The government, media and farming lobby are getting together to make sure that consumers subsidize unprofitable dairy farms.

I think the key here is that once you have some money, the government finds many ways to take that money away from you, and those ways tend to scale as a percentage of your income for people in the range that we are talking about ($1000-$100,000). Being able to afford a place to live has a minimum threshold which depends on the average income in your country.

If you (in the west) fall behind in this race to make enough money so that once the government has thieved from you at both ends you can still afford a room to live, you end up falling into the homelessness trap which is very hard to escape from and is actually worse than the life of a median person in India.

undefined @ 2017-04-06T20:10 (+3)

Just a quick aside: currently the mean individual income for a US college grad is about $77,000. If you have a kid, that's a bit lower, and these are 2016 figures, which makes them a bit higher. Still, I think upper middle class implies higher earning than the mean college grad.

See footnote 2 here: https://80000hours.org/career-guide/job-satisfaction/

I think of 'upper middle class' as jobs like doctor, finance, corporate management. The means here are quite a bit higher e.g. the mean income of doctors in the US is over $200k.

undefined @ 2017-04-07T07:28 (+6)

In my experience, what the Brits humbly call "upper middle class" is what Aussies would call upper class.

yboris @ 2019-09-24T03:02 (+1)

An interactive chart comparing incomes between and within countries: