Instructions for modifying the Moral Parliament Tool

By Hayley Clatterbuck @ 2025-10-16T21:03 (+12)

In this guide, we will provide instructions for adapting the Moral Parliament Tool. We include:

- A more detailed overview of the components of the tool

- A guide to specifying the problem space for a new parliament

- Instructions for making edits in the website

- Instructions for making edits via the spreadsheet method

Components of the Tool

The Moral Parliament tool has three components:

- Specifications of delegates’ worldviews

- Worldviews’ judgments about projects

- Methods for aggregating worldview judgments

Worldviews

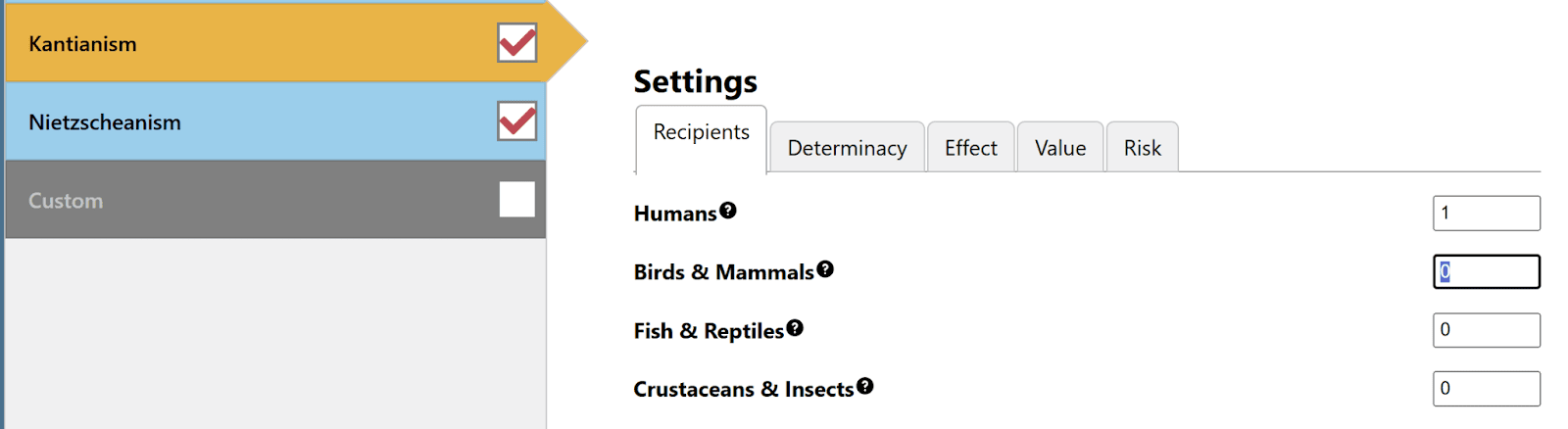

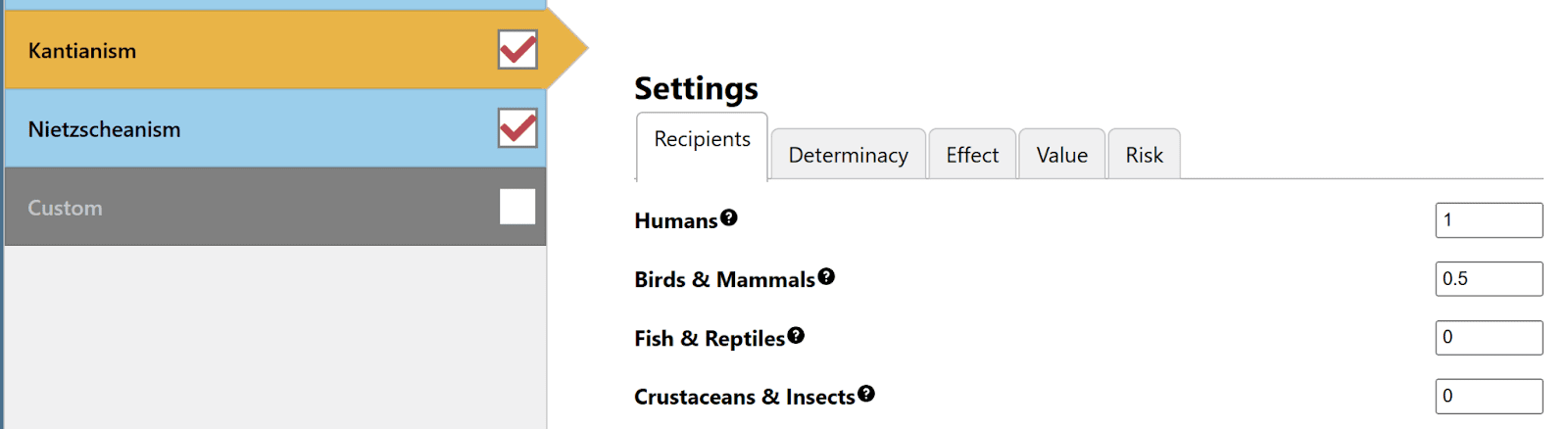

A worldview’s commitments on the various normative dimensions are represented by numerical weights. For example, one key dimension might be Species of Beneficiary. Some worldviews value animals quite highly, while others don’t consider them to be moral patients at all. This is reflected in a linear measurement of moral status, with 1 representing full moral status and 0 representing no moral status. Notice that these values do not need to add to 1; a worldview could assign 1 (or 0, or any other number) to every dimension.

Most of the normative dimensions in the model are simple magnitude scales, like the Beneficiary dimension above.

The dimension of Risk is more complex, as it puts weight not on certain kinds of effects but higher-order distributions of effects (e.g., penalizing or rewarding projects with high variance in outcomes). A risk-neutral worldview judges all outcomes using equal standards, while a risk averse worldview puts more weight on avoiding bad or unlikely outcomes.

Projects

The delegates in the Moral Parliament deliberate over a set of candidate projects. The Tool helps us derive how each delegate would evaluate each project, in light of their worldview. The overall score (or utility) that a worldview gives to a project is a function of how well that project promotes the things the worldview cares about. This depends on two factors:

Scale: the magnitude (or scale) of the project’s effects is how much good the project would achieve if one were to fully value all of the things the project does. To calculate the scale, imagine a worldview that assigns a value of 1 to everything the project does, and then determine how much value the project would create by the lights of that worldview.

Proportion of benefits by dimension: Second, we ask what proportion of the overall effect is valued by the worldview. This latter step is broken down by normative dimensions: we take the proportion of the project’s effects that promote some dimension, multiplied by the importance the worldview places on that dimension. Then, to get the overall score, we multiply the scores for each dimension.

For illustration, consider a project that relieves suffering in 100 million shrimp (and does nothing else). Because 100% of its benefits go to shrimp, it assigns 1 to that beneficiary type and 0 to the others. A worldview that doesn’t think shrimp are morally considerable will find no value in this project: the project’s scale will be multiplied by the 0 moral weight given to shrimp. A worldview that places significant moral weight on shrimp will assign a high score to this project.

A project may have multiple effects that a worldview may assess differently. For example, a project might have a very small chance of producing a significant positive effect on humans and a very large chance of having a negative effect on animals. Instead of trying to characterize the aggregate effect of these two impacts, you can choose to “Add another effect” to the project.

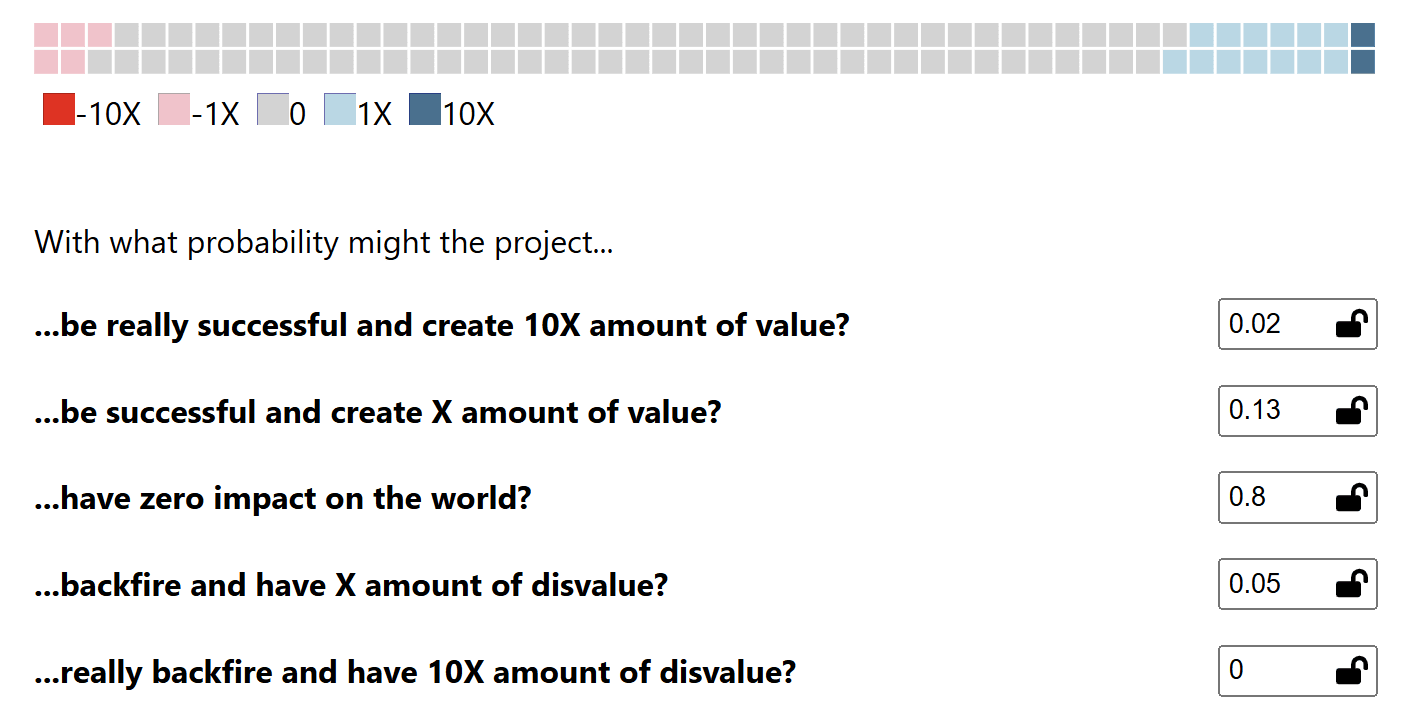

Once again, Risk works slightly differently from other dimensions. A project’s scale is an estimate of the expected amount of good it will do. This expectation may conceal considerable variance in the outcomes that could result. A project’s risk profile is an estimate of the probability that it will achieve some multiplier of its expected Scale. For example, this project has a high (0.8) chance of doing nothing, some chance of overperforming, and some chance of backfiring. As a result, a worldview that is averse to inaction will likely disfavor this project.

To ignore the Risk dimension, you can set the probability that the project is “successful and creates X amount of value” to 1 and all the other values to 0.

Allocation methods

Delegates enter the democratic deliberations having assigned scores to each project. An allocation method is a function from these scores to an ultimate choice of a project or allocation. The Moral Parliament Tool includes a suite of different procedures, including:

- Voting: approval, Borda, ranked choice

- Bargaining: Nash bargaining, proportional allocation (Moral Marketplace)

- Social choice functions: maximin, Maximize Expected Choiceworthiness, My Favorite Theory

The output of an allocation method is a choice of a project or an allocation.

For illustration, in approval voting, delegates decide whether they approve or disapprove of each candidate. We model this in the Parliament by supposing that a delegate will approve of any candidate that they assign a score above some threshold. The winner is the candidate who has the highest number of approval votes.

Once you’ve selected an allocation method, you can adjust its settings by clicking “Edit settings” next to “Results”. Diminishing marginal returns is important for every allocation method. Some allocation methods have special options. For example, for approval voting, you can change the threshold at which delegates will approve of an allocation, or you can change the methods for breaking ties.

Adapting the current web tool

Editing in the site

For a video walkthrough, visit Customize your Moral Parliament

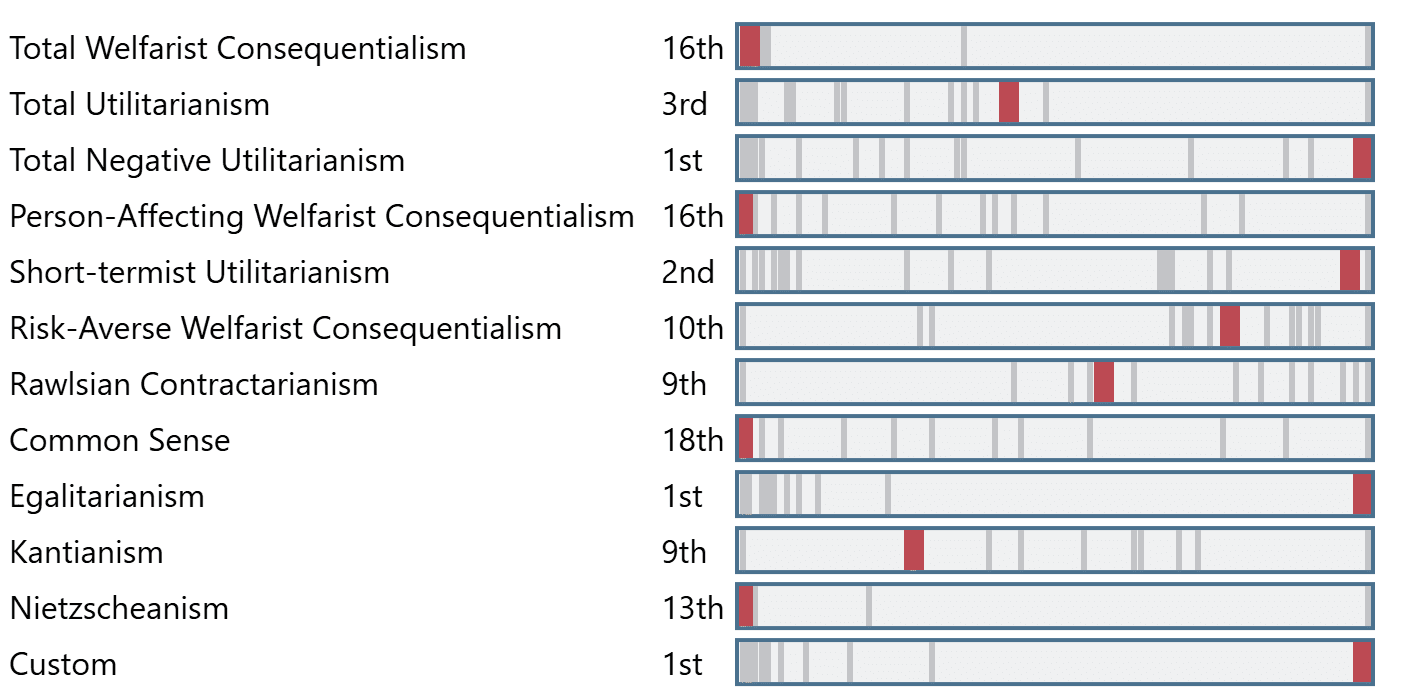

Perhaps you want to use the given worldviews and projects, but disagree with some of the values we have entered. For example, suppose you think that Kantianism assigns too low a score to Mammals and Birds. You can enter what you take to be the correct moral weight. Once you have done so, the tool will update automatically:

If you would like to add a worldview, you can select “Custom” and fill in its values for each normative dimension. You can modify existing projects and worldviews until they align with the ones you want. However, you will not be able to rename, delete, or add new ones.

Changes made through the site will not be saved when you exit. You can save edits via the spreadsheet method below.

Editing via spreadsheet

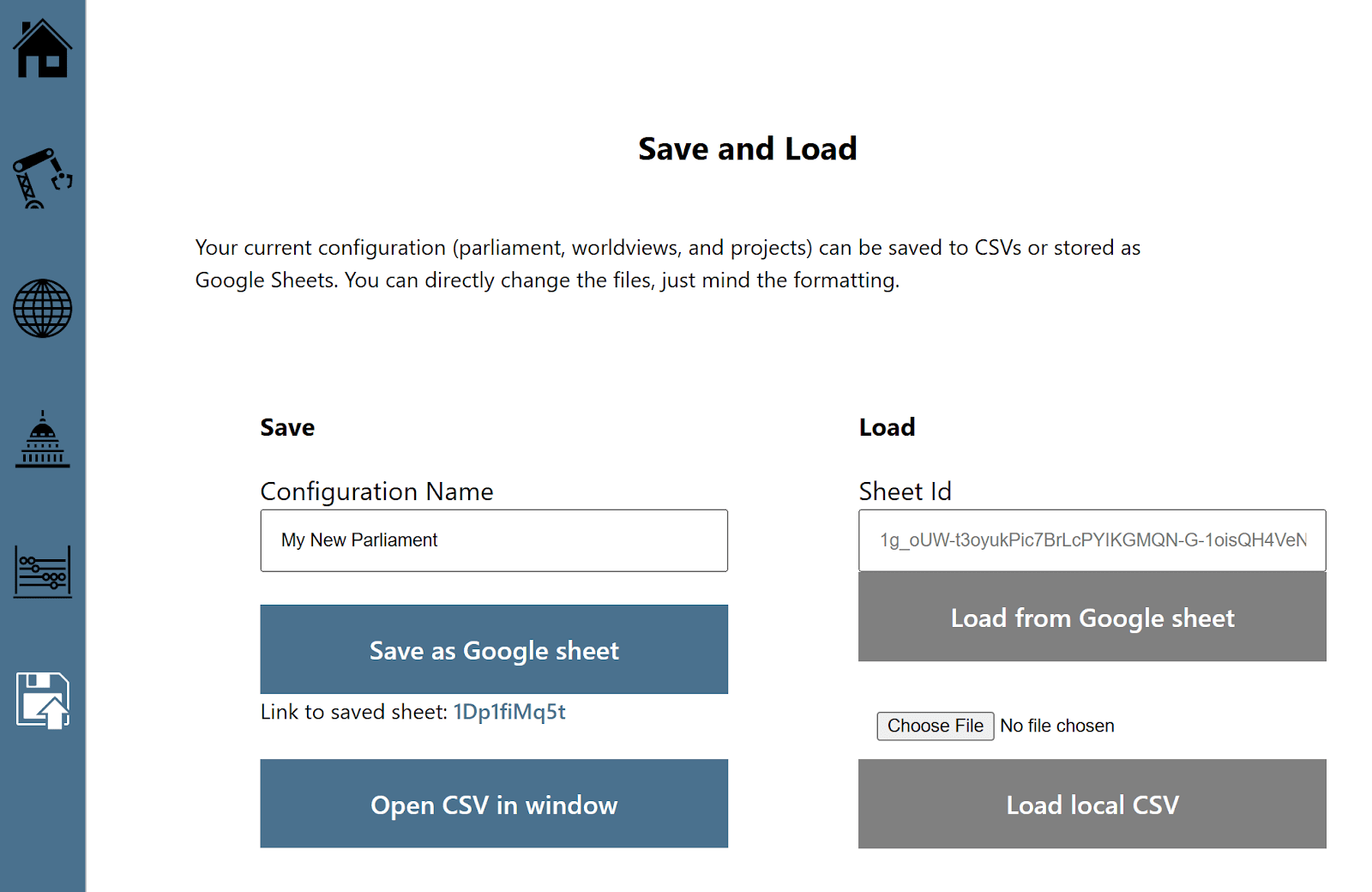

The spreadsheet method allows you to design a parliament with unique projects, worldviews, and normative dimensions (it does not allow you to change the allocation methods). To fully customize the Tool for your purposes, you can use the “Save and Load” function, which updates the tool as specified by user-edited Google Sheets or CSV files (we’ll illustrate this with Google Sheets).

Start by giving your new Parliament configuration a name and selecting “save as Google sheet”. Then, the “link to saved sheet” will open a spreadsheet containing all of the project and worldview information.

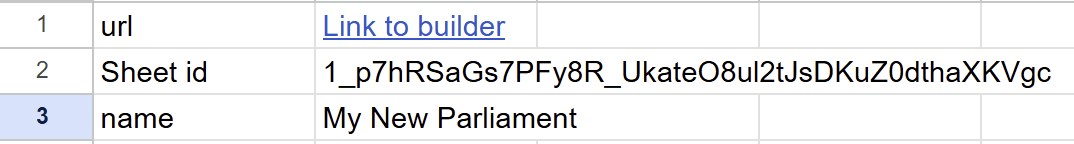

At the top of the spreadsheet, you will find identifying information about your parliament. You can use the “Link to builder” to open up your custom sheet or enter the “Sheet ID” to load from the sheet.

The spreadsheet then lists:

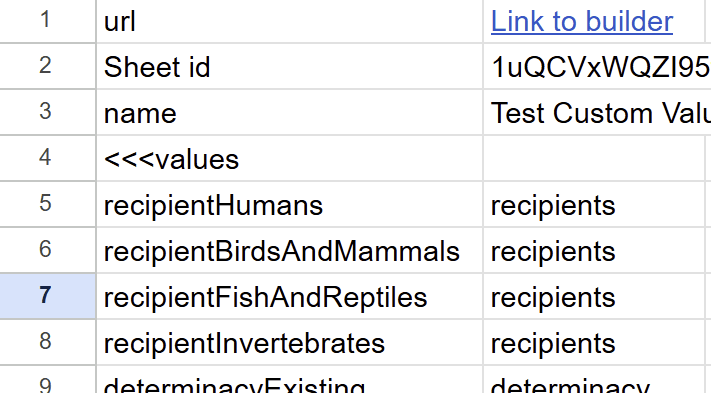

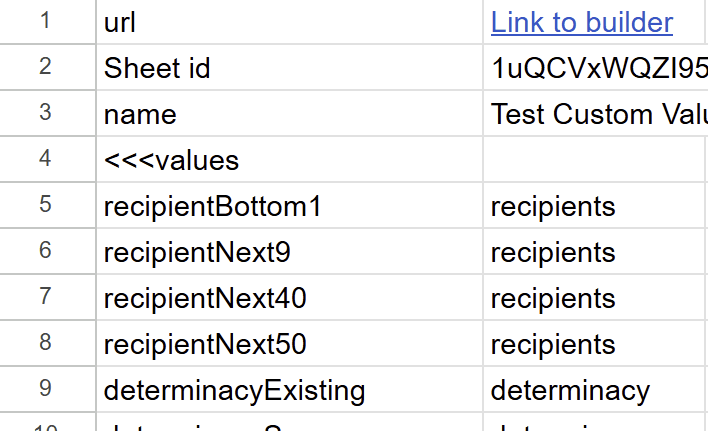

- Normative dimensions, under <<<values

- Projects under consideration, under <<<projects

- Worldviews, under <<<worldviews

By editing the spreadsheet, you can:

- Change project and worldview names

- Delete projects and worldviews

- Add projects and worldviews

You can also change the normative dimensions:

- Assign new scores for worldviews and projects

- Rename or delete dimensions

- Replace existing normative dimensions with new ones

- Add a new normative dimension

If you change normative dimensions, you must make the corresponding changes for every project and worldview in the spreadsheet. For example, I have replaced the “species of beneficiary” dimension with one that classifies beneficiaries by how poorly off they are (i.e., they’re in the bottom 1%, the next 9%, the next 40%, or the top 50%).

Under each worldview and project, I need to replace the old beneficiary categories with the new ones, along with their new scores.

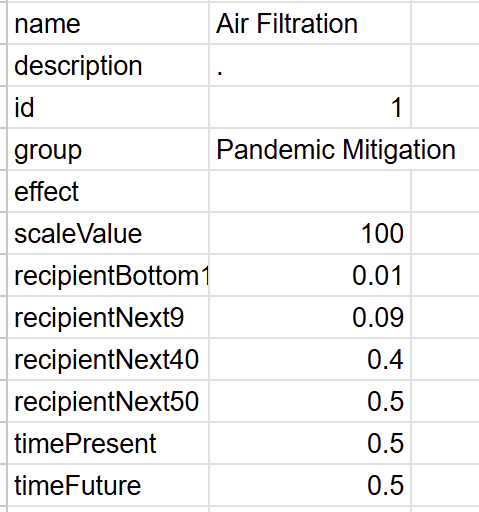

To construct new projects, give them a name and a unique ID number. Then, specify their scale and the proportional distribution of benefits across each normative dimension. Within a dimension category (e.g., recipient, time), the scores should add up to 1.

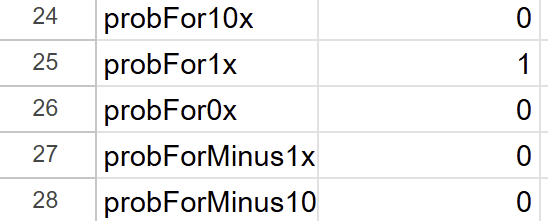

The Risk dimension includes assessments of how probable it is that a project will yield some multiplier of its expected Scale (e.g., achieving 10x what it is expected to). To nullify the dimension of risk, set the probability of achieving 1x scale to 1 and all other outcomes to 0. That will ensure that each project will achieve precisely the scale that you specify:

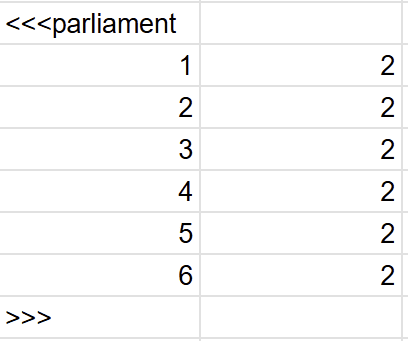

At the end of the spreadsheet, you should specify which worldviews will be entered into the parliament. Be sure that the ID numbers of every worldview that you want to include are entered on the left (the right notes how many representatives they will initially have, which is easily adjustable in the tool).

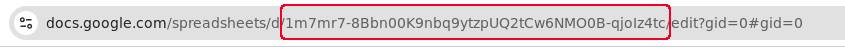

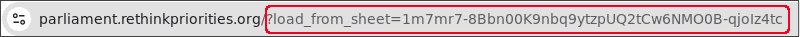

Once you have made the desired changes, load your spreadsheet using the sheet ID. Google supplies this ID, and you will also see it in the URL. If the sheet does not load, that means that there is an error in the spreadsheet. You can proceed to make changes via the newly customized site or the associated spreadsheet.

You may make a copy of your sheet for further edits, but you will need to update the sheet ID in the relevant Parliament Tool URL to get your new sheet to load.