ASI Already Knows About Torture - In Defense of Talking Openly About S-Risks

By Kat Woods 🔶 ⏸️ @ 2025-12-11T21:15 (+2)

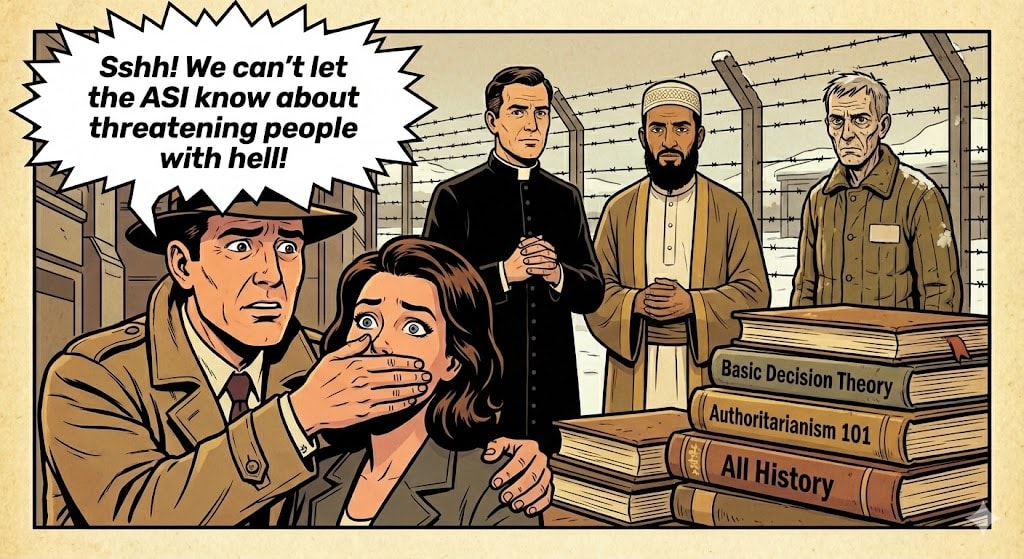

Sometimes I hear people say they’re worried about discussing s-risks from threats because it might “give an ASI ideas” or otherwise increase the chance that some future system tries to extort us by threatening astronomical suffering.

While this concern is rooted in a commendable commitment to reducing s-risks, I argue that the benefits of open discussion far outweigh this particular, and in my view, low-probability risk.

1) Why threaten to simulate mass suffering when conventional threats are cheaper and more effective?

First off, threatening simulated beings simply won’t work on the majority of people.

Imagine going to the president of the United States and saying, “Do as I say, otherwise 1050 simulated beings will be tortured for a billion subjective years!”

The president will look at you like you’re crazy, then get back to work.

Come back to them when you’ve got an identifiable American victim that will affect their re-election probabilities.

Sure, maybe you, dear reader of esoteric philosophy, might be persuaded by the threat of an s-risk to simulated beings.

But even for you, there are better threats!

Anybody who’s willing to threaten you by torturing simulated beings would also be willing to threaten your loved ones, your career, your funding, or yourself. They can threaten with bodily harm, legal action, blackmail, spreading false rumors, internet harassment, or hell, even just yelling at you and making you feel uncomfortable.

Even philosophers are susceptible to normal threats. You don’t need to invent strange threats when the conventional ones would do just fine for bad actors.

2) ASI’s will immediately know about this idea.

ASIs are, by definition, vastly more intelligent than us. Worrying about “giving them ideas” would be like a snail worrying about giving humans ideas about this advanced tactic called “slime”.

Not to mention, it will have already read all of the internet. The cat is out of the bag. Our secrecy has a negligible effect on an ASI's strategic awareness.

Lastly, and perhaps most importantly - threats are just . . . super obvious?

Even our ancestors figured it out millennia ago! Threaten people with eternal torment if they don't do what they’re told.

Threatening to torture you or your loved ones is already standard playbook for drug cartels, terrorist organizations, and authoritarian regimes. This isn’t some obscure trick that nobody knows about if we don’t talk about it.

Post-ASI systems will not be learning the general idea of “threaten what they care about most, including digital minds” from us. That idea is too simple and too overdetermined by everything else in their training data.

3) The more smart, values-aligned people who work on this, the more likely we are to fix this

Sure, talking about a problem might make it worse.

But it is unlikely that any complex risk will be solved by a small, closed circle.

Even if the progress in s-risks had been massive and clear (which it has not so far), I still wouldn’t want to risk hellscapes beyond comprehension based off of the assessment of a small number of researchers.

In areas of deep uncertainty and complexity, we want to diversify our strategies, not bet the whole lightcone on one or two world models.

In summary:

- S-risk threats won't work on most humans

- Even the ones it would work on, there are better threats

- ASIs won't need our help thinking of threats

- Complex problems require diversified strategies

The expected value calculation favors openness

James Faville @ 2025-12-11T23:30 (+46)

The object-level arguments here have merit, but they aren't novel and there are plausible counterarguments to them. It remains unclear to me what the sign of talking about these topics more or less openly is, and I do think there's a lot of room for reasonable disagreement. (I'd probably recommend maintaining roughly the current level of caution on the whole - maybe a little more on some axes and a little less on others.)

But on the meta-level, I think posting a public argument for treating a potential infohazard more casually - especially with a somewhat attention-grabbing framing - is likely quite unilateralist.

The procedure I'd recommend people in this situation follow would be to thoroughly discuss scepticisms about infohazardyness privately with people who are more concerned. Then if you still disagree, you can try to get a sense for the spread of opinions and evaluate whether you might be falling victim to the unilateralist's curse.

(Possibly you did do all that already! In case you haven't I'd suggest pulling this post until you've had the opportunity to get more feedback on it first.)

It's usually much easier to avoid publicising a potential infohazard and reasons to talk more about it, than it is to try to take those actions back later. Public discourse on topics like this might also be biased towards the side of less caution, since arguments on whether a potential infohazard is in fact infohazardous are often going to involve some of the object-level discussion that more concerned people will want to avoid.

Kat Woods 🔶 ⏸️ @ 2025-12-12T01:20 (+22)

Yeah, I've already spoken privately to a bunch of people about this and haven't heard any arguments that have changed my mind.

I'd love to hear counterarguments though! Perhaps there are ones I haven't heard that would change my mind.