A Human Abundance Agenda

By Richard Y Chappell🔸 @ 2025-07-09T15:15 (+8)

This is a linkpost to https://www.goodthoughts.blog/p/a-human-abundance-agenda

Review (#2/2) of After the Spike

Spears and Geruso’s After the Spike: Population, Progress, and the Case for People releases today! In Part 1 of my review, I explained why we should be worried about below-replacement global fertility and subsequent depopulation. Today’s post asks what we should do about it.

What NOT to do: crude coercive measures

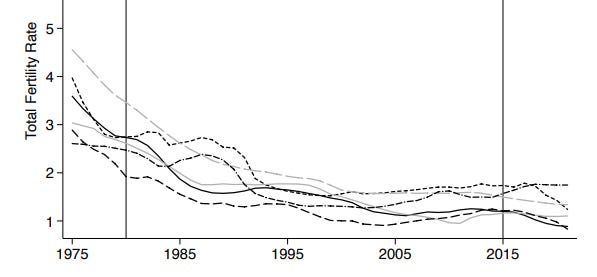

Chapter 4 shares a striking personal anecdote about how restricting reproductive healthcare (e.g. in Texas) can deter couples—esp. those at high risk of miscarriage—from trying for a(nother) child. Chapter 10 adds more systematic empirical evidence that state coercion is ineffective at changing population-wide fertility trends. The following graph, for example, shows the trends for China during their One Child Policy (1980 - 2015) alongside various other countries that lacked this policy:

The other countries shown include Hong Kong, South Korea, Taiwan, and Thailand, plus Romania (where abortion was outlawed in an attempt to increase the birth rate). But it’s not at all obvious from the trend lines which countries were coercively anti-natalist, which coercively pro-natalist, and which were neither. Spears and Geruso conclude:

Population control has never controlled the population. Birth rates and population trends are beyond coercive command and control.

Ultimately, individuals make their own choices, and attempts at coercive control fail to shape long-run outcomes. Accordingly:

There will only be a future with many children in it if people choose to have them. Parenting must be attractive if we expect people to choose it—and choice is what will matter in the long run.

Things that might help a little, or are good regardless

One often hears that people “can’t afford” to have children anymore. This is implausible on its face: the world is richer than it’s ever been, so in absolute terms we literally can afford to do more of whatever we want than could past generations. But if standards have also risen in the meantime, it may be that it’s much more expensive now to raise a child in accordance with social expectations. There’s certainly a lot of expense involved! But Spears and Geruso point out that differences between states in the rise of housing and childcare costs make no observable difference to fertility trends. They suggest that the issue is less about affordability and more about opportunity costs:

The opportunity cost hypothesis: Spending time on parenting means giving up something. Because the world has improved around us, that “something” is better than it used to be.

It would be nice to have more generous parental leave policies, “baby bonuses”, subsidized childcare (or, what IMO would be better: equivalent cash for families to use as they see fit, whether that’s for external childcare or supporting a stay-at-home parent), etc. Standard pro-family policies are good to have, not least because a society is shooting itself in the foot if it allows something as simple as mere financial obstacles to deter some otherwise willing parents from having a(nother) child. But these sorts of policies won’t suffice to get fertility back above replacement.

Similar things can be said of fertility treatments and other improvements in reproductive technology (artificial wombs?) that make it medically easier for those who want to become parents to do so. Good things, for sure. Well worth investing in. Still, S&G invite us to imagine that all you had to do was press a “baby button” and your newborn baby would appear in your arms. Would enough people choose to press the button enough times? Given current trends, it seems not; so we need more than just medical improvements (for all that they are welcome!).

What to try next?

The simple answer is that we need to do everything we can to make parenting easier and more appealing. Start brainstorming!

After discussing past radical social transformations—from public schooling to sanitation to social security—Spears and Geruso write:

Could radical change come to parenting or family life, too? Could we expect something wholly different from each other and from our communities and governments? In the most modest of possible improvements, could we expect, for example, a future in which the perpetual challenge for parents of what to do with kids in the summertime or on the days when school is off but work is on is just… solved? Not a scramble, not a stress, not a conflict. Solved? Of course we could. That would mean choosing it as societies, not as individuals.

While individual altruism is good and welcome, they especially emphasize that “Big challenges need policy, technical, and social change.” We should be willing to radically transform the economy, if necessary, by massively investing in making parenting easier and more appealing (including via astronomically larger child tax credits and such)—I’d say: something that gets closer to the huge positive externalities of a human life, including all the future tax revenues that an additional child can be expected to pay back to society in adulthood.[1] As S&G write:

Is avoiding depopulation so much less affordable than the rest of what fits in societies’ budgets? One of the best things humanity could do with its wealth and resources is to make it easier to choose children.

Spears and Geruso don’t say much about policy specifics here. They’re hoping to start a conversation rather than conclude one. Hopefully others will join the brainstorming, and once we have a better view of our options, we’ll be in a better position to prune, prioritize, and select between them.[2]

Further thoughts

Something that jumps out to me is the need for cultural change to promote both implicitly and explicitly pro-parenting attitudes and norms.

In many social circles, there’s a conditional norm that if you become a parent at all, then you had better be the most dedicated, perfect parent the world has ever seen.[3] This norm is implicitly anti-natalist. If we want children to exist, we need to welcome more half-assed parents into the fold, and be truly bloody grateful for their contribution to humanity’s future. As Ozy Brennan explains, Moral Standards For Parenting Need To Be Achievable By Mediocre People, or else there simply won’t be enough eligible parents left to sustain the species.

Anything that grants higher social status to parents seems worth considering. A lot of cultural effort in past decades went into removing any stigma from being “childfree by choice”, and part of that process involved treating parenting as just another hobby. Some people collect stamps, some rescue and care for stray animals, and some create and raise the next generation of people. Pick whatever personally appeals, it’s no-one else’s business.[4] That’s the standard message, right?

I think what we need instead is for society to valorize parents and parenting, the way American society valorizes veterans. No-one is forced to join the armed forces, or stigmatized for choosing a different career path. But American society says “thank you for your service” in many ways, big and little, and if it properly internalized the fact that creating and raising people is even better (and more difficult) than killing them, maybe it could find a way to provide similar social recognition for the service done by parents and families. (Again, this shouldn’t require stigmatizing anyone who makes different life choices.)

In sum, if we hope to maintain human abundance and avoid depopulation, society needs to offer an adequate mix (possibly all) of:

- Massive boosts in financial support to families of young children.

- A thorough restructuring of society and public spaces to make parenting easier and more convenient in all respects, reducing the opportunity costs of choosing children.

- Cultural change to make parenthood feel higher status and more socially valued.

Post-AI Economic Restructuring?

While the details remain murky, AI is clearly going to cause massive economic upheavals. But one area where humans plausibly have a lasting advantage is in care work.[5] We might even welcome a future in which people (on average) work less on computers and more with children. More childcare; more micro-schools with tiny student : teacher ratios; more general sharing of the joys and burdens of raising the next generation.

I also hope that improving information technology will eventually deliver on its promise to boost social coordination and connections. Make it easier to connect attention-needy kids with lonely elder folk. Make it easier for families with similar values and similarly-aged kids to meet, co-ordinate, and—if they want to—even create co-housing mini-villages together.[6] Make it easier for families to form “communities of interest” within their local neighborhoods (or maybe VR/AR advances will allow even geographically distant friends to appear and share in one’s local space).

These may be wistful hopes, but one never knows what the future holds. Check out After the Spike, and let me know: in your more optimistic visions of a future in which we successfully reverse the falling fertility trends, how did we do it?

- ^

Here’s an interesting way to think about it: How much should a government be willing to pay in order to have an extra lifetime taxpayer? If there aren’t enough non-state parents, one could imagine the state stepping in to hire people every step of the way (from surrogacy to wet nurses, full-time childcare, and schooling) to reach its desired number of future taxpayers. Now, considering the mottled history of state-run orphanages, it’s surely preferable to instead spend that money on encouraging and supporting parents to do all this socially valuable work instead!

Or another thought, this time from Robin Hanson: we could actually reduce the per-capita future debt burden by incentivizing each extra birth via debt-funded spending up to that per-capita level! (Though I assume this only works if we don’t then promise to pay more social security and medicare to those new kids in their old age? Otherwise that would cut into the amount we could spare to subsidize their childhood.) Here’s Robin’s key paragraph:

The U.S. national debt is now officially $33T, but add in promises to pay social security, medicare, etc, and I find published estimates of $100T, $147T, and $245T for what the U.S. has promised to pay out somehow via taxes. Divide these by the current U.S. population to get a debt per citizen ranging from $300K to $730K. We should thus be willing to pay up to these huge amounts up front to induce the birth and raising-to-adulthood of a single child who would then pay average levels of future taxes to repay this debt.

- ^

A minor critique: Spears and Geruso frame the alternative to depopulation as “stabilizing” the population at replacement level. This seems a fine rhetorical device to avoid triggering old traumas about “overpopulation”. But it matters more substantively to their argument that it’s urgent to “care now”, even though the Spike is still decades away: The longer we take to “rebound to replacement”, they argue, the smaller the resulting stable population level will be—potentially by billions—“in perpetuity.”

But if we do manage to reverse the fertility trend line, there’s no reason to expect it to stop precisely at replacement (just as there was nothing to stop it there on the way down). So if we do manage to solve this within the next century or so, it seems plausible that humanity could rebound as high as we collectively want to, given time. Of course, I’ll join the authors in lamenting the missing lives that might have been in the meantime. But at least there’s the potential for future growth if desired, even if we take longer to stabilize than would be ideal.

(I don’t take this to undermine their core contention that it is well worth starting to address the problem early. Humanity would be better off now if previous generations had not been so slow to move on climate change. That’s true even if future technology enables us to reverse atmospheric greenhouse gasses, and not just stabilize them. It’s worth addressing problems early!)

- ^

Some even propose explicit regulation to license parents, though at least that’s more focused on preventing outright abuse rather than attaining parental perfection.

- ^

Another standard thought: “Don’t expect others to subsidize your hobby.” (Or as Jessica Gross writes: “I find that I get more and more pushback for the idea that raising children is a community responsibility… Pretty consistently, I get responses that boil down to: If you can’t afford kids, that’s on you. You chose to have them. But I think that’s both unempathetic, and shortsighted…”)

- ^

At least until AI of sufficient quality can be embodied in very realistic human-like robots, as in Westworld.

- ^

Imagine if you could easily find neighborhood “blocks” of four houses backing into a shared private courtyard/playground where the families’ kids could play together. (Apartment complexes might offer such amenities shared by hundreds of unchosen others. Single-family housing combines control with isolation. It would be nice to have more options in-between.)

SummaryBot @ 2025-07-09T21:17 (+1)

Executive summary: This evidence-based and exploratory review of After the Spike argues that reversing falling fertility trends and preventing long-term human depopulation will require comprehensive efforts—including massive financial support for families, policy and societal restructuring to lower parenting opportunity costs, and cultural change to elevate the social value of parenthood—since coercive or marginal policy tweaks have historically failed to influence fertility at scale.

Key points:

- Coercive population policies—both pro- and anti-natalist—have historically failed to significantly alter long-term fertility trends, underscoring the need for voluntary, incentive-aligned approaches.

- Rising opportunity costs, not affordability per se, appear to better explain declining fertility, as modern parenting increasingly competes with more attractive alternative life pursuits.

- Incremental support policies like childcare subsidies and baby bonuses are worthwhile but insufficient, and must be part of a broader agenda to make parenting systematically easier and more appealing.

- Cultural norms that excessively idealize parenting contribute to declining birth rates, and a shift toward recognizing and valorizing “good-enough” parenting could help make child-rearing more accessible and less daunting.

- Spears and Geruso advocate for large-scale public investment in parenting infrastructure, akin to past radical transformations in education or public health, potentially justified by the long-term fiscal and social benefits of higher fertility.

- The review suggests leveraging AI-driven economic changes to elevate care work and build better community infrastructure, aiming to lower parenting burdens and increase the social desirability of raising children.

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.