Phlourish since 2023

By Shen Javier @ 2025-08-20T06:34 (+34)

Overview

Phlourish aims to expand mental health support for Filipinos through cost-effective interventions. From piloting to launching a guided self-help program for adolescents, we have reached more than 900 users through 23 partner organizations. They are found all over the Philippines, reaching 25 cities and municipalities in 12 provinces.

We spend around PHP 1,000 (USD 17.50) to provide mental health information and support per user, leading to improvements in life satisfaction and important behaviors.

We are creating new programs to address more mental health gaps in the Philippines. We will stay ambitious and evidence-based as we grow the organization for accessible mental healthcare and flourishing lives for all.

About Phlourish

Phlourish is founded by three members of the effective altruism community in the Philippines. Together, the team has background and experience in operations, science communication, research and data analysis, organizational development, government consulting, and social work.

Our goal is to test and scale interventions for mental healthcare to be accessible to Filipinos. We envision that by delivering impactful mental health interventions, we can help foster flourishing lives.

What we’ve been up to

Development of our first program (Q3 2023 to Q1 2024)

Our guided self-help program takes inspiration from the findings of the Mental Health Charity Ideas Research Project. Previous studies on guided self-help have shown effectiveness in addressing various mental health outcomes and it is known to be one of the most cost-effective mental health interventions.

We focused on adolescents because they are at a crucial period for growth and development. The Philippines ranks as the 2nd country in Southeast Asia with the highest number of healthy life years lost to mental health conditions in 5- to 24-year olds.[1] This was further supported by the 2021 Philippine National Survey on Mental Health and Well-being which found that 1 in 5 children and adolescents (22.2%) developed at least one mental health condition in the past year[2]. Additionally, the 2024 Global School-Based Health Survey reported that among Filipino Grade 7 to 10 students in public high schools, 21.7% experienced suicidal ideation and 27.3% had attempted suicide within the past year[3].

Despite these significant findings on adolescent mental health, the problem remains neglected. Philippine’s profile data in the 2020 Mental Health Atlas (WHO, 2022) shows that there are only 28 child and/or adolescent psychiatrists in the country and a total of 357 mental health workers in child and adolescent local mental health services[4]. The 2021 national survey also revealed that 40.6% reported facing structural barriers to accessing mental health care, such as inaccessibility, lack of services, cost, and difficulties in securing appointments[2].

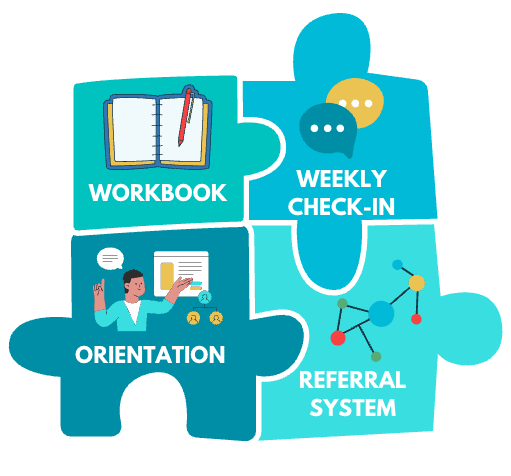

It is in this backdrop that Phlourish decided on its first program: guided self-help workbooks for adolescents. Our program is built around four core components: the toolkit or workbook, weekly check-ins with mentors, orientations, and a referral system.

The program was developed based on focus group discussions with adolescents and parents, and consultations with mental health professionals. Experts also reviewed the toolkit to ensure its content was age-appropriate and of good quality. Before the pilot, we conducted user testing to refine the toolkit’s language, design, and usability. The toolkit is designed by metaFox, a company creating emotional intelligence tools for people development professionals and enthusiasts.

Piloting guided self-help (Q1 2024 to Q3 2024)

The pilot engaged 198 adolescent participants across eight areas in the Philippines (urban, semi-urban, and rural), supported by two partner organizations. We present the results of the pilot following our goals:

[1] to determine the effectiveness of the self-help toolkit in improving mental health outcomes among Filipino adolescents

Among those who completed the program, 47.7% (31 participants) improved by at least one category on the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS). Among participants who were initially Slightly Dissatisfied or Slightly Satisfied, 91.7% and 92.3% respectively moved up by at least one category. Overall, there was significant improvement in SWLS scores, with a medium effect size of 0.46 (p < 0.001). Participants also showed significant gains in 9 out of 14 measured mental health outcomes which are aligned with the toolkit’s lessons.

User feedback and mentor observations provided further evidence of the program’s impact. Adolescents shared meaningful takeaways from the workbook and reflected on how they applied these in their personal lives. Mentors reported that impactful concepts shared by adolescents matched workbook chapters. Parents also observed positive changes in their children including more openness and improved communication.

[2] to determine the acceptability of the self-help toolkit among Filipino adolescents, parents, and other stakeholders

The program was well-received, earning a final average rating of 9.75 out of 10. Among program completers, toolkit reading and activity completion rates were high, at 86.1% and 73.7% respectively. Participants appreciated the content and visual design of the toolkit, noting that it was engaging, easy to understand, and helped them reflect and apply mental health strategies. Mentoring was also highly valued; participants cited the supportive and approachable style of Phlourish Lay Mental Health Mentors as a key strength. Parents expressed strong support for the program, motivated by wanting to help their children go through adolescence with greater emotional awareness and balance.

[3] to determine the cost-effectiveness of the self-help toolkit

The average cost per pilot participant was $19.76 or PHP 1,100. With an average increase of 2.37 SWLS points per program completer, this results in a cost-effectiveness estimate of approximately $8.39 or PHP 439.27 per one-point increase in life satisfaction.

Overall, Phlourish finds the results of the pilots promising with identified areas for improvement including understanding mechanisms of impact, participant recruitment, and implementation models for scale. We are excited to bring the guided self-help program to more adolescents and help them lead flourishing lives.

You may read the full report of the pilot here.

Launching guided self-help (Q1 2025 to present)

After our successful pilot, we set a goal to reach 3,000 users for our guided self-help toolkit in 2025. By mid-July, we had reached 710 users. While we have encountered challenges in engagement, we are encouraged by users’ motivations—many want to learn about and care for their mental health, understand and manage their emotions, and explore self-discovery. Most have not yet received any mental health programs, and nearly half face barriers to accessing services.

Initial results show some positive signs: improvements in life satisfaction, anxiety and depression symptoms, and other mental health outcomes. Users are also giving high ratings to the program. We will share a full report after this year.

Piloting new programs (Q2 2025 to present)

We have gained valuable insights from our pilot and the implementation of our first guided self-help cohort. Gaps in mental healthcare remain widespread across the country and our current program is just one of many needed interventions. Some populations and areas continue to be overlooked, even though effective solutions do exist. While the pilot results and early signs from the first cohort are promising, challenges in recruitment and maintaining engagement have prompted us to explore additional ways to support adolescent mental health.

We assessed our strengths and areas for improvement, to leverage our capabilities for new initiatives. We have identified opportunities within our current guided self-help program and generated ideas inspired by different sources. We also conducted a survey among our users about what a mental health program should look like. This has led us to compile a list of potential programs to expand our impact. We then narrowed the list using this criteria:

- Effectiveness

- Acceptability

- Ease of Scaling

- Feasibility

- Costs

- Ease of Funding

- Risk Mitigation

- Potential Reach

- Neglectedness

We decided on the following three:

- Subgranting of the guided self-help workbook program: We will expand our current program by providing small sub-grants and training to organizations in low-resource settings that aim to improve the mental health and well-being of their adolescent clients, community members, beneficiaries, or learners. We launched the call for subgrantees in June and received around 30 applications. Training and implementation will continue through the rest of the year. More information about the subgranting program can be found here.

- Group psychoeducation workshop series: This intervention offers skills-focused mental health education in a group setting, with sessions lasting 1-2 hours over four to five weekly meetings. Lay mental health providers, trained with 10-40 hours of preparatory coursework and ongoing supervision, will facilitate these sessions. The content will adapt the current program’s workbook material to focus on areas like self-compassion, emotion regulation, or help-seeking. We plan to pilot this series in November.

- Parenting SMS program: We want to extend our efforts to parents and caregivers of the adolescents we serve, recognizing that the quality of parenting is closely linked to mental health and development. This program, called PM-Sent (Parenting Messages for Supportive Engagement), will provide parenting information through text messages sent over the course of four weeks. The goal is to improve parental competency and mental health, parent-child relationships, and youth mental health. The pilot is set to begin in August, with a limited number of slots open to the public to be announced on our page.

We will share more information about these new programs after the pilots.

Biggest wins

- We created a workbook covering key mental health learnings which can be adapted for other programs like our group psychoeducation and parenting SMS program. We also developed a youth engagement methodology called the IHA/O framework.

- We already reached areas in Luzon, Visayas and Mindanao—the Philippines’ three island groups—showing our commitment to bringing mental health support to all Filipinos. We engaged diverse partners, such as small communities, municipal and city governments, provincial and regional level government agencies, non-government organizations, schools and universities, residential facilities for at-risk children, youth organizations, even business entities.

- We grew our team from three to seven members, each bringing unique strengths and experiences but sharing passion for mental health.

- We crafted a comprehensive Child and Youth Safeguarding Policy, complete with a Safeguarding Orientation and Code of Conduct, with guidance and reviews by child protection practitioners and experts. We share this with partners so they can adopt it if they do not have one yet. This is an essential yet often overlooked part when working with adolescents.

- We trained 171 lay mental health mentors on program content, adolescent engagement, monitoring, safeguarding, and identifying high-risk situations. We consider this a huge contribution given the country's limited number of mental health workers.

Biggest challenges

- Low mental health awareness affects adolescents, parents, and partners. Many teens think they don’t need prevention programs, while parents worry about stigma, and partners find the term “mental health” negative or confusing. Despite efforts to correct these misconceptions, it still impacts participation, and culturally relevant promotional strategies remain difficult to develop due to varying contexts.

- The lack of structural and environmental support for mental health complicates implementation. Without established referral systems or a culture that normalizes help-seeking, many individuals may recognize their needs but lack accessible pathways to get support, limiting the program’s overall impact and sustainability.

- There is a gap in an overarching mental health framework in the government. Our coordination with various government agencies and offices (education, health, social welfare, and population development) have been positive but it also highlights how easy mental health services can be fragmented when they should be part of broader systems. A lot has improved since we started the program with new laws passed and we are excited to be part of this momentum.

Biggest errors

- We underestimated what it meant to scale. As we expand nationwide, we observe differences in adolescents’ demographics—such as age, education, and access to phones and reliable internet—as well as variations in partner reach, capacity, and type. These differences affect interest and commitment to the program and adapting to them while maintaining quality is possible but challenging. Managing and monitoring simultaneous runs of the program also proved to be difficult given these differences and our growing reach.

- We did not measure improvements in anxiety and depression symptoms in the pilot. Initially, we considered measuring these symptoms but expert consultations highlighted risks like stigma, self-diagnosis, misinterpretation, and criticism from mental health professionals especially given the low mental health literacy in the country and our status as a new organization. However, we could have still included these measures in our outcomes and prepared more for how to communicate them, learning earlier about the program’s possible effects on said mental health conditions.

- We did not partner with organizations on referral systems during the pilot, which is crucial in areas lacking safeguarding mechanisms and response capacity. In one area, the absence of local connections made direct referral difficult; although we managed to resolve it, having other options beforehand would have made the process easier.

Biggest lessons

- Implementations might be more effective when they are delivered and led by partners themselves, highlighting the value of sub-granting. This approach fosters ownership, contextual relevance, and sustainability, as partners are better positioned to tailor the program to their specific settings and needs.

- Outcomes for adolescents are more meaningful when interventions also target their environment, such as involving parents and engaging schools and teachers.

- Adolescents have varied preferences regarding the level of guidance they seek from mentors. This variability shows the need for flexible approaches to find the balance between engagement and effectiveness for different individuals.

What’s next

For the rest of 2025, we aim to:

- Continue reaching our goal of 3000 users for the guided self-help program through direct implementation and subgranting

- Pilot and evaluate the parenting SMS program and the group psychoeducation workshop series

- Partner with an international non-profit and a national university to pilot a teacher-training design capacitating teachers to identify and manage mental health concerns in their students

For the years ahead, our plans will be highly dependent on this year’s progress and pilot results. If all programs remain promising, we hope to:

- Refine our direction as an organization that tests and scales mental health interventions

- Further build our organizational structure to support our programs

Collaborate with us

We are launching an internship program soon! Learn while helping us with our implementation, monitoring and evaluation, and administrative processes. Stay tuned for the call on our Facebook page.

We are always excited to connect with others who share our mission. As a growing organization, we’re actively looking for opportunities to learn, share, and collaborate—and we would love to support others doing the same.

We are especially open to working together in the following areas:

- Implementation and M&E: We welcome feedback and collaboration to strengthen our implementation and improve how we monitor and evaluate our work.

- Program partnerships and research: If you have ongoing programs, research ideas, or are exploring ways to deliver mental health support in the Philippines or elsewhere.

At the same time, we are more than happy to support others who are entering the mental health or nonprofit space. We believe in growing a strong ecosystem and are always eager to share what we have learned and learn from others.

If you see any opportunity to connect, collaborate or even just exchange ideas, please do not hesitate to reach out.

Facebook: www.facebook.com/people/Phlourish-Mental-Health-Initiative-Inc/

Email: contact@phlourish.ph

Website: www.phlourish.ph

- ^

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. (2021). GBD results. Retrieved from https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results?params=gbd-api-2021-permalink/4de00b774ce196e0af18721adb2dd52b

- ^

National Survey on Mental Health and Well-being. (2021). 2021 Philippine National Survey on Mental Health and Well-being. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/NSMHW2021

- ^

World Health Organization. (2024). Philippines: 2024 Global School-based Student Health Survey (GSHS) fact sheet. Retrieved from https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/ncds/ncd-surveillance/data-reporting/philippines/2024-gshs-philippines-fact-sheet.pdf?sfvrsn=227cabae_1&download=true

- ^

World Health Organization. (2022). Philippines profile. Mental Health Atlas 2020 country profiles. Retrieved from https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/mental-health/mental-health-atlas-2020-country-profiles/phl.pdf?sfvrsn=45d0ca2b_5&download=true

John Salter @ 2025-08-20T20:54 (+4)

Great write up! I especially like how candidly you wrote about the errors.

SummaryBot @ 2025-08-20T14:49 (+2)

Executive summary: Phlourish, an EA-founded nonprofit in the Philippines, has piloted and launched a cost-effective guided self-help program for adolescents that shows promising improvements in life satisfaction and mental health outcomes, and is now scaling through partnerships, subgrants, and new initiatives such as group workshops and parenting support.

Key points:

- Program impact: The guided self-help toolkit—combining workbooks, mentoring, orientations, and referrals—improved life satisfaction (medium effect size 0.46, p<0.001) and other mental health outcomes among adolescents, with strong acceptance ratings (9.75/10).

- Cost-effectiveness: At ~$19.76 per participant, or ~$8.39 per one-point increase in life satisfaction, the program compares favorably with other low-cost mental health interventions.

- Scaling efforts: Having reached over 900 users across 23 partner organizations, Phlourish aims for 3,000 users in 2025, with expansion supported by subgrants, training, and a growing mentor network (171 trained).

- New pilots: In 2025, they are testing three additional interventions: (a) subgranting the workbook program, (b) group psychoeducation workshops, and (c) a parenting SMS program (PM-Sent).

- Challenges and lessons: Barriers include low mental health awareness, structural gaps in healthcare systems, and difficulties in scaling across diverse contexts. Lessons highlight the value of partner-led implementation, environmental interventions (involving parents, schools), and flexibility in mentoring styles.

- Next steps and collaborations: Beyond user growth and program pilots, Phlourish plans teacher training collaborations, further organizational development, and welcomes partnerships in implementation, M&E, and research.

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.