Transformative AI and Animals: Animal Advocacy Under A Post-Work Society

By Kevin Xia 🔸 @ 2025-05-25T18:32 (+64)

Thanks to Max Taylor, Irina Gueorguiev, Robert Praas, Albert Didriksen, Mark Rogers and Justis Mills (EA Forum) for feedback on this post. All mistakes are my own. This post does not necessarily reflect the views of my employer.

Executive Summary

- This post explores how farmed animal advocacy might change in a post-work world enabled by transformative AI (TAI), mass automation, and universal basic income (UBI). It is not a forecast, but a speculative exploration, intended to surface underexplored questions at the intersection of AI, economic systems, and animal advocacy.

- Implications for animal advocacy may include labor becoming abundant and funding becoming less of a bottleneck. However, much current advocacy work may be handled by AI in the process and effective strategies should be “human-scalable” and asymmetrical—leveraging advantages the industry can’t easily copy.

- Industrial Animal Agriculture may persist on various grounds that our movement needs to be ready to tackle, such as tricky consumer behavior influences, cultural identity/narratives, institutional inertia, maintaining political influence and moral complacency.

- I present a list of open questions that I think are important to explore to fully take transformative AI seriously in our efforts to help animals.

Contextual Notes

This piece explores the evolving roles of industrial animal agriculture and farmed animal advocacy in a society shaped by transformative AI (TAI).[1] As an illustrative example, I explore mass automation, universal basic income (UBI) and the emergence of a post-work society (i.e., a society in which people can live well without being economically compelled to work).[2] I chose to explore this scenario, because I find it to be the most compelling among genuinely transformative scenarios - and because I find the implications particularly illustrative.

However, this piece does not intend to be read as a forecast. I don’t intend to claim or defend the likelihood of post-work, the constraints and milestones to get there, nor any particular implications of post-work for farmed animal advocacy efforts. Instead, I hope to pose questions that I believe to be underexplored at the intersection of post-TAI economics, industrial animal agriculture and farmed animal advocacy, and to illustrate their potential implications and relevance through this example.

Introduction

With AI systems exponentially improving in many areas, forecasts of when we develop artificial general intelligence have generally become shorter, with many predicting AGI in the next 5-10 years. These systems, then, could have transformative effects on our society, the economy and how we do things, including our efforts to end factory farming. Some authors have talked about “a century in a decade” or similarly accelerated rates of development, which, if we can sufficiently address the risks associated with such compressed lines of events, could bring us reason for excitement.[3] But even in cases where we avert many of these risks, things don’t necessarily look rosy for non-human animals. Preparing for these types of scenarios seems increasingly urgent. This piece examines a generally positive outcome post-TAI (a UBI-powered post-work society)[4] and explores possible changes in the dynamics of farmed animal advocacy efforts and industrial animal agriculture.

What becomes of systems like factory farming, which are justified by its perceived efficiency, and the desire to protect agricultural workers? And on the flip side, what becomes of non-profit work when money, wages, and time are no longer the central constraints?

Post-Work Farmed Animal Advocacy Work

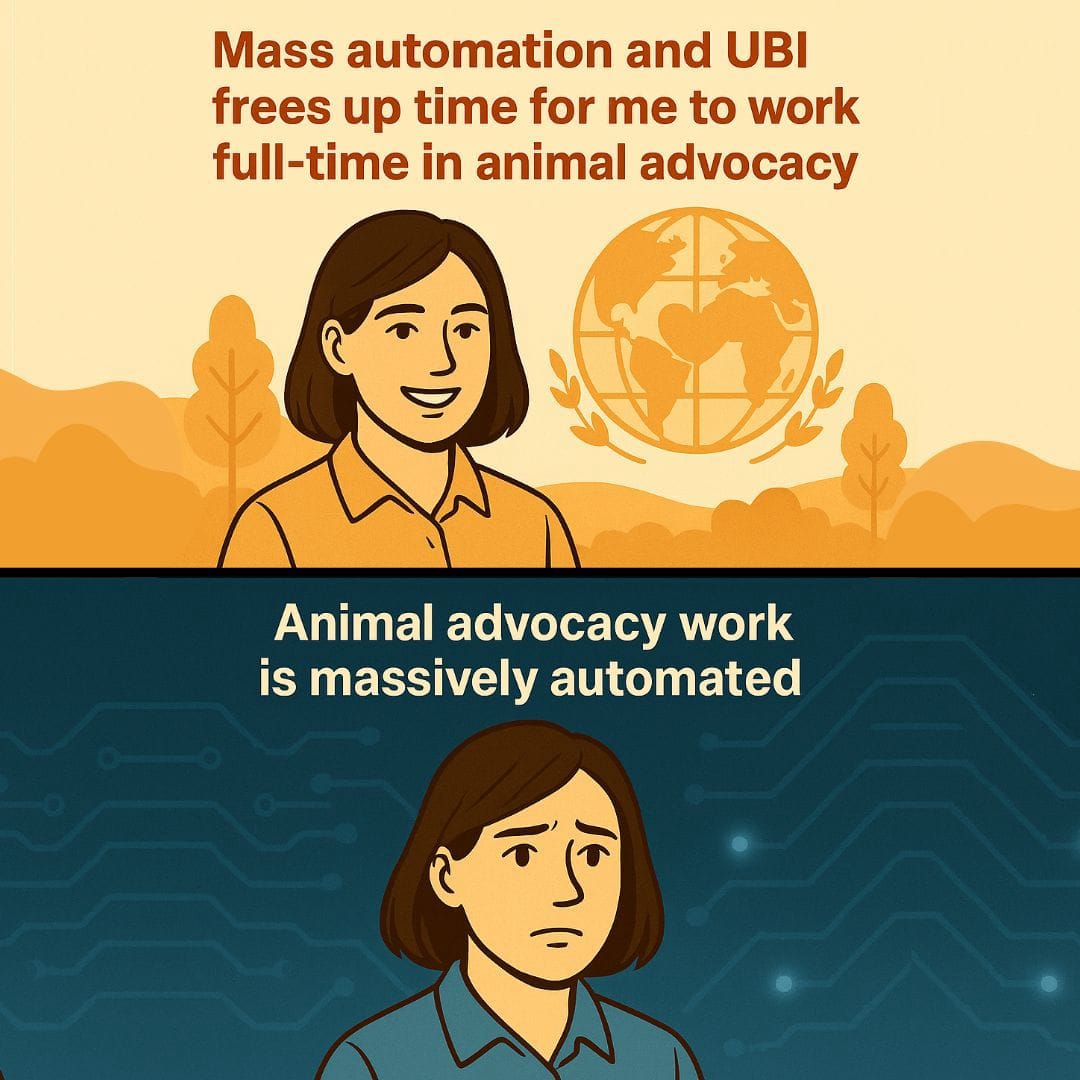

Non-profits today, especially in the farmed animal advocacy movement, are largely constrained by funding. Notably, this funding is primarily used to pay staff members, as we need people to dedicate their full-time work hours to helping animals.

A post-work society changes this calculus. When people are no longer bound to paid employment, they may choose to contribute to causes they care about out of alignment rather than necessity. We may see passionate, capable individuals engage in advocacy full-time without requiring salaries—massively increasing the labor pool for mission-driven work and in some ways leveling the playing field.

This shift could also challenge traditional organizational design in many ways, some for the better, some for the worse. With AI staff available, new non-profits may be started left and right (including by representatives of industrial animal agriculture), effectively drowning each other out as they compete for stakeholders’ attention. Rather than recruiting staff, non-profits might cultivate distributed networks of contributors. Movement governance might shift toward decentralized collaboration, with AI supporting coordination and knowledge sharing.

However, our current spending on advocacy efforts may not be reflective of the post-TAI scenario. If cutting-edge AI remains paywalled for organizations, spending may simply shift from labor to AI capabilities, leaving us funding-constrained nonetheless. Moreover, the very same mass automation through TAI that enables this talent pool would also automate much of the work that nonprofits do. So what remains for humans to do in farmed animal advocacy?

I am skeptical of attempts to predict which exact roles will remain better done with humans in the loop, but some loose guesses of the type of work we could be looking at include:

- Work that requires or benefits from human connection or trust (e.g., community building, networking-heavy work around policy or corporate engagement, or major donor fundraising).

- Work that requires or benefits from significant context with messy data (e.g., some elements of non-profit entrepreneurship, strategic comms judgment).

- Work that requires or benefits from real people showing up (e.g., mass-movement mobilization, protests).

Notably, it remains unclear whether and to what degree these roles even persist. For example, how important is major donor fundraising, if we are not primarily constrained by funding? The question, then, is about finding, preparing for and effectively leveraging human-scalable strategies[5] that are robust against or even greater in potential under the economic system that enables them. Furthermore, it would be helpful if these strategies, then, would be asymmetrical, i.e., could not be just as easily deployed by the industry or a movement to defend the industry.

Post-Work Industrial Animal Agriculture

At first glance, one may be hopeful that in a post-work, abundance-oriented society, factory farming may just cease to exist. If animal products can be replaced by cheaper, more ethical alternatives—and if profit no longer drives production—why would factory farms still exist? A couple of reasons seem plausible:

- Doubts about Alternatives: Cheaper and more ethical alternatives (e.g., price-competitive cultivated meat) seem like a solid bet, but consumer choices are tricky. It is unclear whether price, taste and convenience parity would be enough to displace conventional animal products. Moreover, we shouldn’t just assume that alt-proteins undercut animal products in price - likely, by the time we have technological developments to make alt-proteins cheaper, we will have even more such developments to make animal farming more efficient. Perhaps, we will find conventional animal products and alternatives both at a price range far below a level where price considerations matter for consumers. This is even more worrisome, considering that now costlier products such as ones from aquaculture may drastically decrease in price and benefit more from efficiency improvements. We will likely need to leverage trickier influences, such as social norms and narratives for consumers to make the change - or somehow convince the industry of the ultimately preferable efficiency and profitability of alternative proteins.

- Cultural Identity and Narrative Power: In many societies, animal agriculture is deeply woven into cultural identity. Factory farming may survive as a symbol of “how things used to be”—defended less for what it provides and more for what it represents. As such, industry actors may shift their strategy from efficiency narratives (“we feed the world”) to cultural ones (“we are heritage, authenticity, community”). In a post-work society, where identity and narrative gain prominence over necessity, this repositioning could preserve influence. On the flip side, once advanced tech is entrenched in most aspects of everyday life anyway, people might also become readier, or be forced, to accept new ways of doing things and move on from their attachment to tradition, including 'traditional' animal agriculture. Either way, we may need to focus on understanding and influencing narrative change under transformative AI.

- Institutional Inertia: Massive infrastructures don’t vanish overnight. The systems supporting industrial agriculture are deeply entrenched. Even if more ethical systems are available, transitioning entire food economies is slow. Companies may drag their feet. Governments may hesitate. Public policy may lag behind technical feasibility. We may need to be able to make a profit case for agile companies to transition away from factory farming, circumventing some of the inertia wherever possible.

- Legacy Power and Political Influence: Even with fewer profit incentives, power remains a potent motivator. Large agricultural firms may retain sway over political processes, media narratives, and regulatory bodies. They may lobby not for survival, but for continued relevance. They might control land, data, or public discourse. Their goals may shift from maximizing revenue to maximizing cultural capital. Currently, the political influence of industrial animal agriculture systems is driven by arguments around the need to protect the agricultural workforce, and it doesn’t seem clear how its political influence will continue to play out post-work.

- Moral Complacency: In a world driven by abundance, choice, alternative forms of sustenance, pleasure and entertainment, people, including perhaps animal advocates, may just stop caring. This seems especially likely if harmful systems are quietly absorbed into the background and factory farms disappear from headlines while continuing in practice, hidden by layers of automation, data opacity, geographic displacement, or displacement underwater. This doesn’t need to be a problem; in a world where no one cares, perhaps those who do care have an advantage, insofar as we can displace harmful systems in a way that doesn’t negatively affect other people or require them to participate.

None of these are certain, but I think they are important to investigate as part of the broader question of how the system of industrial animal agriculture may (want to) be upheld under transformed economies.

Open Questions for Farmed Animal Advocates

As noted before, I don’t have any answers or specific recommendations, other than the mere fact that we should think more deeply about how the system around us will change under transformative AI and how that may affect our predictions on leveraging AI interventions. To re-emphasize, my intentions are primarily to pose these questions, such that other people can provide answers and meaningful recommendations to the movement. As such, here is a list of questions that came up as I explored the dynamic of a transformed economic system and how it changes the dynamics of industrial animal agriculture and farmed animal advocacy work:

- Which economic systems are likely to happen post-TAI and what do they entail for industrial animal agriculture and farmed animal advocacy efforts?

- Do any of these systems seem particularly likely to benefit animals? How can we work towards them?

- Can these systems be assumed globally? Where can we expect significant regional differences and what do they imply?

- Which preparations can we take to be robust against different economic systems?

- What does the “road to” any specific economic system tell us about opportunities and risks? In this article, I have assumed and “started off” in a post-work society, but the transition period may prove even more important to navigate.

- Based on the transformative changes we may expect, should we spend down in this unique time to help farmed animals or save our resources and recollect ourselves once things stabilize?

- What motivations may relevant actors have to uphold industrial animal agriculture?

- How would a post-work society reshape our thinking about profit incentives and money as a key factor in career decisions?

- Can we shift norms to sufficiently deprioritise money as a career factor that makes it undesirable for any given person to keep industrial animal agriculture afloat?

- Will alternative forms of entertainment and pleasure-seeking outweigh any remaining monetary incentive for relevant actors?

- How can we engage with corporations to transition from factory farming to alternative proteins?

- If we make a sustainability/efficiency/health argument, how do we make sure that they don’t transition to e.g., aquaculture?

- How can we think of consumer choices at price ranges in which price parity doesn’t/barely matters?

- What tricky factors are most likely to remain uninfluenced by alternative proteins that are only just competitive on price, taste, and convenience, and how can we influence them?

- How can we affect social norms/narrative/cultural change under transformative AI?

- How can we think of non-profit work in a post-work society? Does it level the playing field to one driven merely by passion, manpower and lobbying capacities?

- Are animal advocacy efforts even scalable (i.e., can we even make use of unlocked talent after resolving funding constraints?)

- What advocacy strategies are best “human-scalable” and asymmetrical? How can we (prepare to) leverage them better?

- Which arguments and bottlenecks “against” explosive growth through AI can be selectively applied to industrial animal agricultural sectors and circumvented by the farmed animal movement? If we can anticipate or ensure that AI will lead to explosive growth in the animal movement but not in the industry, this may present a huge opportunity.

- Even post-work, what resources remain significantly scarce and what do they imply for our movement? E.g., land could be a scarce resource and thus beef more expensive.

- What are the new/key bottlenecks in a post-AI economy and how can we address them? E.g., attention seems to be a good candidate, so how can we focus on better on it?

- What other sci-fi tech developments may occur to render factory farming obsolete? (Think, e.g., developments that don't replace animal products, but rather the very act of eating )

Closing Thoughts

At its core, a post-work future would not just be a policy shift, but a moral turning point. If we can eliminate suffering at scale, if no one needs to work in exploitative conditions, if we can replace harm with compassion, then failing to do so becomes a deep ethical failure. The legitimacy of factory farming today largely rests on a perceived trade-off: economic efficiency versus harm. For many, this trade-off is already indefensible, so what if it disappears?

The challenge, then, is not just to make alternatives economically viable, but to make compassion culturally inevitable. In a world where no one has to work, some will still choose to do so—not for wages, but for meaning. Farmed animal advocacy may be one such calling. Yet to remain relevant, it must evolve. We must prepare for a world where traditional leverage points, such as funding, labor, or outrage, may lose potency. We must anticipate the narratives that legacy industries will adopt. And we must invest in cultivating moral imagination, cultural influence, and future vision.

- ^

In line with the EA Forum Topic, I define Transformative artificial intelligence (TAI) as artificial intelligence that constitutes a transformative development, i.e. a development at least as significant as the agricultural or industrial revolutions. This does not, technically, require artificial “general” intelligence in the sense that it does not need to be able to perform all or almost all tasks that humans can perform.

- ^

A post-work society isn’t necessarily one where no one works—it’s one where work is no longer a prerequisite for survival or a decent life. People may still choose to work for meaning, identity, status, or social contribution, but not to meet basic needs. I find it helpful to log different economic scenarios on a scale that compares “average work week” vs. “quality of life” - you’d have 60 hour work weeks to "survive" a century ago, to 40/35 hour work weeks today and would continue to scale towards 20 hour, 10 hour and ultimately “0” hour work weeks, first to survive/to live a decent live (i.e., post-work) and ultimately to thrive (i.e., post-scarcity).

- ^

I, for one, would have expected the end of factory farming in less than 100 years. The prospects of getting there in a decade feels absurd, but we should probably expect absurd things to play out under transformative AI.

- ^

The idea here is usually that AI systems would become increasingly capable at cognitive tasks and remote tasks, including helping design robots and other physically embodied systems that would further replace physical tasks. The idea that such AI systems would actually lead to mass automation, that mass automation would lead to job losses and that job losses would lead to UBI are all far from obvious, but assumed for the purpose of exploring this radically transformative system.

- ^

I.e., strategies that increase significantly in effectiveness with the number of humans involved.

Karen Singleton @ 2025-07-11T23:34 (+1)

Thanks for this thoughtful and expansive post, it really succeeds as an invitation to think about animal advocacy under radically different economic conditions. I appreciated how it foregrounds questions over predictions, especially around how cultural narratives, institutional inertia and new leverage points like attention and moral imagination might shape the future of factory farming.

This connects closely to research I’m currently doing on how different economic paradigms may reduce (or risk entrenching) animal exploitation (I hope to share a Forum piece on it soonish).

Your piece helped clarify some key gaps in current discourse, particularly around AI-aligned paradigms where animals are often entirely absent unless explicitly centred.

I particularly appreciated your attention to asymmetrical strategies and the need for advocacy to remain relevant in a landscape where labour and funding may be less of a bottleneck, but attention and narrative become the scarce resources.

It’s exciting to see this kind of cross-paradigm, long-view thinking on the Forum. I hope we see more of it!