Participatory Learning and Action (PLA) groups for maternal and newborn health - AIM top idea 2024

By Ambitious Impact, Aidan Alexander, weeatquince🔸 @ 2024-04-05T11:42 (+12)

TLDR: This report explores the idea of incubating a nonprofit organization that will focus on improving newborn and maternal health in rural villages by training facilitators and running PLA groups – a specific type of facilitated self-help group.

We’re seeking people to launch this idea through Ambitious Impact (Charity Entrepreneurship) next August 12-October 4, 2024 Incubation Program. No particular previous experience is necessary – if you could plausibly see yourself excited to launch this charity, we encourage you to apply by April 14, 2024.

Research Report:

Participatory Learning and Action (PLA) groups for maternal and newborn health

Author: James Che and Aidan Alexander*

Review: Sam Hilton

Date of publication: February 2024

Research period: 2023

*Aidan Alexander did the cost-effectiveness analysis and wrote the section on it. James Che wrote and did the research for the rest of the report.

We are grateful to the experts who took the time to offer their thoughts on this research.

Additionally, thanks to all Charity Entrepreneurship staff who contributed to this report.

For questions about the content of this research, please contact James at james@charityentrepreneurship.com. For questions about the research process, please contact Sam Hilton at sam@charityentrepreneurship.com.

Executive summary

Charity Entrepreneurship (CE) fosters more effective global charities by connecting capable individuals with high-impact ideas. In 2023, CE investigated ideas related to sustainable development goals and potential neurotoxicants or toxic substances.

Maternal and neonatal disorders are significant causes of global mortality. In 2020, out of the 135 million births worldwide, there were approximately 1.4 million stillbirths and 2.4 million neonatal deaths (OWID, Boerma et al., 2023). Maternal mortality is also high, with an estimated 300,000 women dying during pregnancy (Boerma et al., 2023).

Despite strides in maternal and newborn health (MNH), the burden remains disproportionately high in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Over 90% of maternal deaths occur in these regions – Sub-Saharan Africa and Southern Asia, in particular, account for 68% and 19% of these deaths, respectively.

Community-based interventions represent a promising approach for rural populations with poor access to institutional healthcare. There is often a significant difference between mortality rates in rural and urban areas, and access to care is much worse in rural areas.

Participatory learning and action (PLA) groups are a simple yet well-evidenced community-based intervention that could be promising to reduce maternal and neonatal deaths. It involves holding facilitated group meetings for women of reproductive age, particularly pregnant women, to foster local strategies that enhance care-seeking behaviors and adopt preventive health practices for better MNH.

Strong evidence supports the effectiveness of PLA in reducing neonatal and maternal mortality. A meta-analysis conducted by Prost et al. (2013), which included seven trials involving approximately 119,000 births, found that when >30% of all pregnant women participated in groups, PLA reduced maternal mortality by 49% and neonatal mortality by 33% amongst all births in the community. In such cases, pregnant women who did not participate also benefited from the group-led solutions.

In addition to maternal and neonatal mortality, we are also excited by the potential positive externalities that PLA groups may have. There is weak evidence that PLA groups could benefit maternal mental health, family planning, under-five child health, community resilience to crop failures, and individual and community agency.

PLA is estimated to be highly cost-effective. The groups can be extremely low-cost to run. Our cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) estimated that hiring and training community workers to run PLA groups full-time would cost ~$20-$70 per DALYs averted. This is equivalent to ~14-47 DALYs per $1000 spent.

Although the maternal and neonatal space is not as neglected as before, this is a relatively neglected intervention within the space. Growing attention and funding are devoted to MNH, and the burden is slowly decreasing. However, this intervention has only been implemented in about 15 countries, with few at scale.

Our geographic assessment identified many countries where a potential new non-profit can target, including Sierra Leone, Nigeria, Guinea, Benin, Côte d'Ivoire, Pakistan, and Guinea-Bissau.

Experts are excited by the prospect of a new non-profit implementing this intervention. GiveWell has been interested in funding this intervention as they think it meets their bar for cost-effectiveness. However, they have been finding it challenging to find implementation partners. Women and Children First, who are the pioneers of the intervention, serve a technical assistance role and are excited to support a potential CE-incubated charity.

We have some remaining uncertainties regarding the intervention. We are unsure whether a non-profit can effectively target and recruit pregnant (or soon-to-be pregnant) women, as reaching a sufficient percentage of them is crucial for effect size and, thus, cost-effectiveness. We also have some uncertainties around whether a new non-profit can implement the intervention at costs comparable to the studies. There is also a weak concern about the external validity of the intervention, as most of the RCTs were conducted in South Asia. We also have some uncertainty around the mechanism behind the reductions in maternal and neonatal mortality, though we have plausible explanations from studies, which alleviate our concern.

Overall, we believe this is an idea worth recommending for incubation. A new organization focused on running and scaling PLA groups for MNH will likely be highly cost-effective.

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Meaning |

| ASHA | Accredited Social Health Activists |

| BEmONC | Basic Emergency Obstetric and Newborn Care |

| CE | Charity Entrepreneurship |

| CEA | Cost-effectiveness analysis |

| CHAI | Clinton Health Access Initiative |

| CHWs | Community health workers |

| CHE | Current health expenditure |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| DALY | Disability-adjusted life years |

| DNTs | Developmental neurotoxicants |

| GBD | Global Burden of Disease |

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product |

| LMICs | Lower and middle-income country |

| MDGs | Millennium Development Goals |

| MNH | Maternal and newborn health |

| NGO | Non-governmental organization |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| OWID | Our World in Data |

| PLA | Participatory Learning and Action |

| RCTs | Randomized controlled trials |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| SHG | Self-help group |

| SMI | Self-management intervention |

| ToC | Theory of change |

| UCL | University College London |

| UN | United Nations |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| WCF | Women and Children First |

| YLD | Years lived with a disability |

| YLL | Years of life lost |

1 Introduction

This report evaluates the idea of participatory learning and action groups for MNH concerning its promise for the CE Incubation Program.

CE’s mission is to cause more effective non-profit organizations to exist worldwide. To accomplish this mission, we connect talented individuals with high-impact intervention opportunities and provide them with training, colleagues, funding opportunities, and ongoing operational support.

CE researchers chose this idea as a potentially promising intervention within the broader areas of (1) the best targets within the Sustainable Development Goals and (2) the burden of neurotoxicants and other dangerous substances. This decision was part of a multi-month process designed to identify interventions that are most likely high-impact avenues for future non-profit enterprises.

This process began by listing hundreds of ideas, gradually narrowing them down, and examining them in increasing depth. We use various decision tools such as evidence reviews, theory of change assessments, group consensus decision-making, case study analysis, weighted factor models, cost-effectiveness analyses, and expert inputs.

This process is exploratory and rigorous but not comprehensive – we did not research all ideas in depth. As such, our decision not to take forward a non-profit idea to the point of writing a full report does not reflect a view that the concept is not good.

2 Background

2.1 Cause area

In this research round, CE focused on two areas within human development and health: (1) the best targets within the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and (2) the burden of neurotoxicants and other dangerous substances. Researching these two areas meant evaluating ideas from various fields, including maternal health, chronic diseases, neglected tropical diseases, migration, public administration governance, neurotoxins, and education.

We considered the different types and variety in the overall quality of evidence one can expect from each field and the limitations of comparing interventions across different cause areas, where different metrics would often be prioritized or preferred. As individuals with experience with CE’s research process will have noted, the diversity within a research round is often limited to avoid these limitations. As such, this research round differed in some ways from the way CE conducts research within a specific cause area.

Best targets within the Sustainable Development Goals

The SDGs are a mechanism designed to focus global action toward specific objectives. Like the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) before them, these goals aim to redirect efforts and funding toward an agreed-upon list of priorities. They were agreed to by the United Nations (UN) General Assembly as part of its post-2015 ambitions (Wikipedia contributors, 2023c). Unlike the MDGs, the SDGs have grown significantly in number of goals and targets (from eight to 17 and 21 to 169, respectively).

The global community succeeded in some of the most critical MDGs. MDG targets related to poverty reduction and safe drinking water, among others, were met. Despite missed targets, observers have noted the role of a concise list of eight priorities in focusing energies and driving progress. By drawing comparisons to the MDGs, observers have criticized the SDGs for being too many in number and too broad in substance (Lomborg, 2023; The Economist, 2015).

Progress toward achieving SDG goals has stalled. Only 15% of SDG targets are on track to completion, 48% are moderately or severely off-track, and 37% are regressing or stagnating (United Nations Publications, 2023).

This research round aimed to investigate if a non-profit organization of the style CE incubates could cost-effectively support the progress toward the goals and associated targets. We used the list of goals from the Copenhagen Consensus’ Halftime to the SDGs project as an initial departure point, listing all interventions prioritized in that project and supplementing the list with research from other sources, such as the Global Education Evidence Advisory Panel’s smart buys in education (Banerjee et al., 2023), and our own brainstorming and consultation exercise.

2.2 Topic area

Maternal and Child Health: The Global Burden

Maternal and neonatal disorders are significant causes of death and disability globally. In 2020, out of the 135 million births worldwide, there were approximately 1.4 million stillbirths and 2.4 million neonatal deaths (OWID, Boerma et al., 2023). Maternal mortality is also high, with an estimated 300,000 women dying during pregnancy (Boerma et al., 2023). MNH metrics are highly correlated.

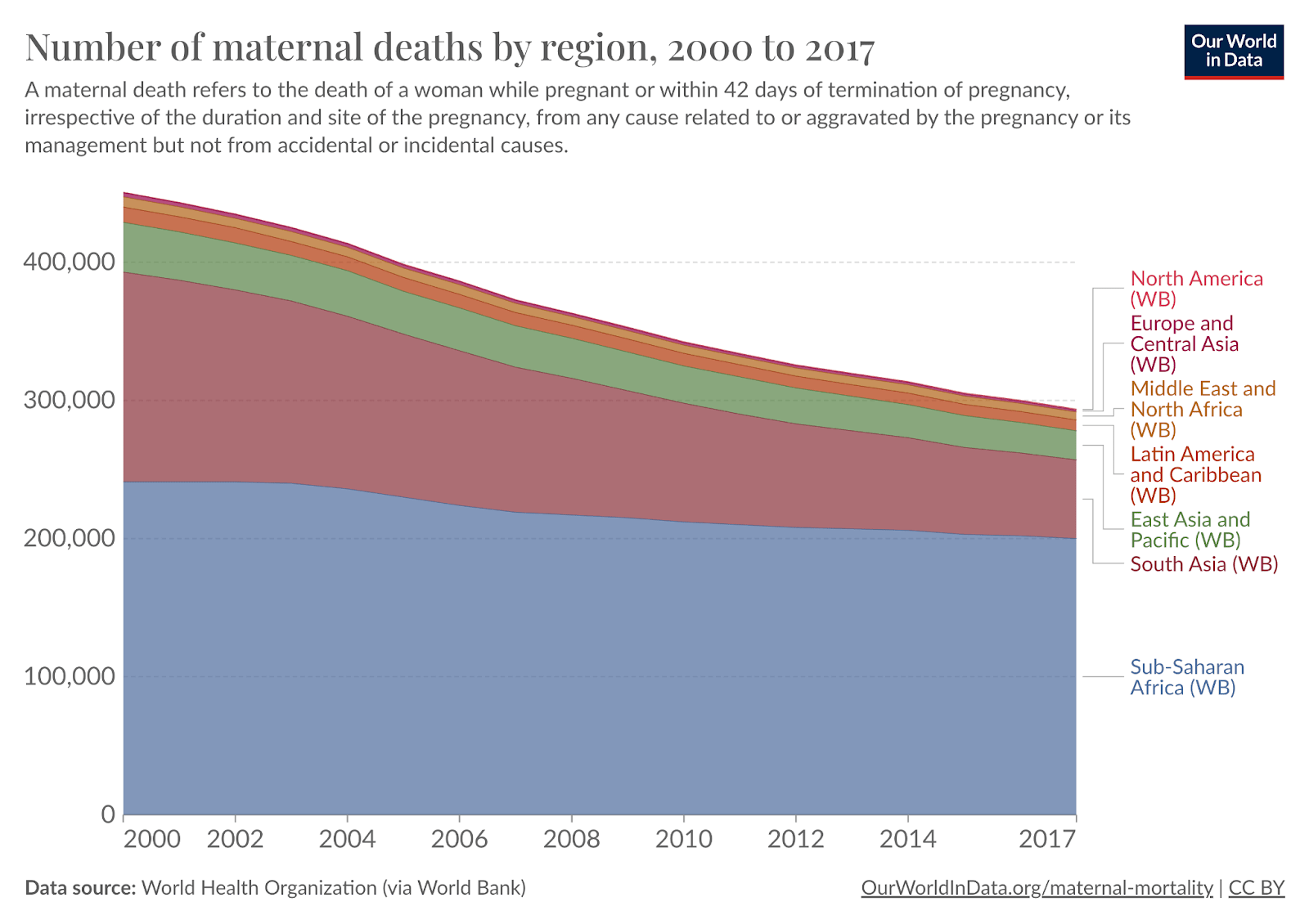

Many countries have made significant progress in MNH, but there is still a high burden in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. In the past, almost every country had child mortality rates of around 50%. Today, because many countries have made significant progress in MNH, the burden of maternal and neonatal mortality falls heaviest on LMICs. Over 90% of maternal deaths occur in LMICs, with sub-Saharan Africa accounting for 68% and Southern Asia 19% in 2017 (OWID). Similarly, 79% of neonatal deaths occur in those two regions (WHO, 2022). These disparities between poor and rich countries suggest that most neonatal deaths are preventable.

Figure 2: The number of maternal deaths is declining globally, but burden concentrates in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia (Source: OWID) |

We are not on track to meet the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The SDGs (Goals 3.1 and 3.2) pledged to reduce maternal deaths to 0.07% and neonatal mortality to below 1.2%, saving about 200,000 women and 1.2 million children from dying annually. However, on the current trajectory, maternal mortality is expected to decline to only 0.16% and neonatal deaths to only 1.5% by 2030. The SDGs aim to reduce the child mortality rate to at least as low as 2.5% in all countries by 2030. Yet globally, 3.9% of all children die before reaching the age of five.

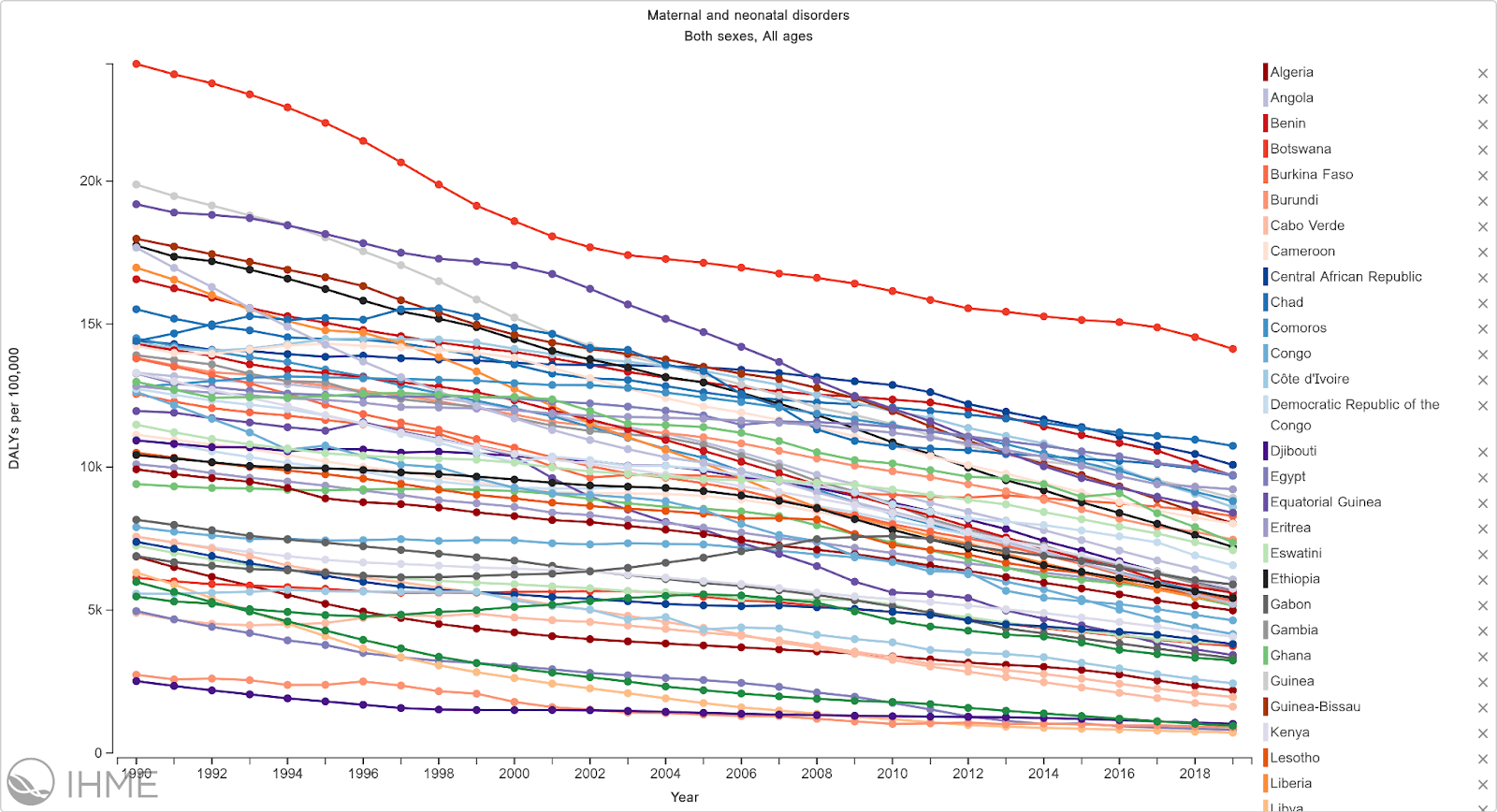

Figure 3: DALY’s lost due to maternal and neonatal disorders in Africa (GBD)

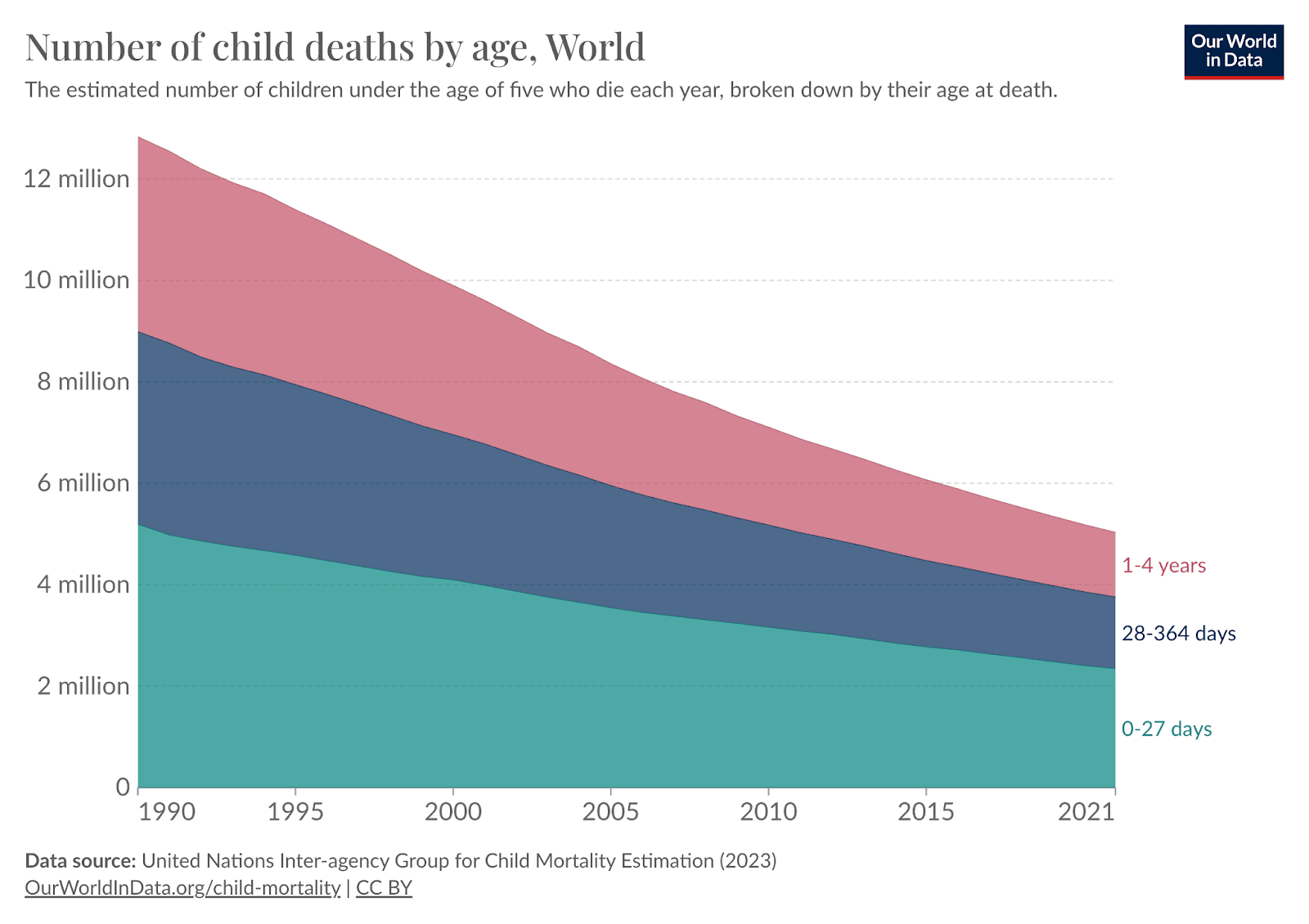

Declines in neonatal mortality have lagged behind reductions in mortality for older children. The field typically separates children into three distinct time periods (Table 1). Briefly, the neonatal period refers to children below 28 days of age; infants below one year, and children below five years of age. Figure 4 shows the historic decline in child mortality in the three age groups. Since 1990, mortality has fallen substantially for 1-4-year-olds (-65%) and infants (<1 year, -58%), but less so for neonates (<28 days, -49%) and babies <1 week (-39%).

Table 1: Terminology used to describe specific periods of development.

| Terminology | Time period |

| Neonatal | <28 days |

| Infant | <1 year |

| Child | <5 year |

Figure 4: Trends in child mortality from 1990 to 2021 (OWID)

The first month of life is the most vulnerable period for a child's survival. In 2020, nearly half (47%) of all under-5 deaths occurred in the neonatal period. Older children tend to die from diseases such as diarrhea, pneumonia, measles, and meningitis. These are vaccine-preventable, so it has been relatively easy to make progress. However, the causes of death in the youngest children are very different. Pre- and post-birth complications – which are the primary cause of death in the early days of life – cannot be directly prevented by vaccinations.

Community-based solutions: Participatory learning and action

To combat the high burden of maternal and neonatal mortality, significant investments are needed across many aspects of care. These range from antenatal to post-natal care; from strengthening the quality of care in facility births to community-based interventions. This report focuses on a specific community-based intervention: PLA, which is a particular type of self-help group (SHGs).

PLA was initially developed by a team from University College London, eventually evolving into Women and Children First (WCF). This method involves facilitating group meetings for women of reproductive age to foster local strategies that improve MNH.

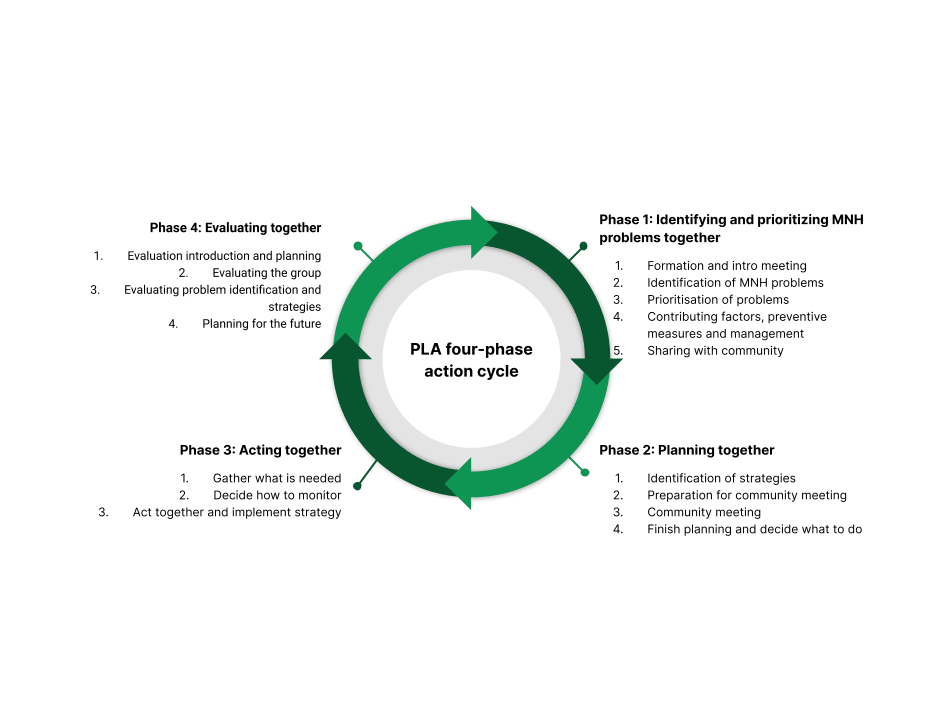

The emphasis in PLA that differentiates it from SHGs is the four-phase action cycle. As illustrated by Figure 5, the PLA meeting process encompasses four distinct stages. In the first stage, facilitators and workers encourage members to recognize and rank MNH issues using visual aids and a voting process. In the second stage, they deliberate and develop potential solutions, which are ranked in priority. Concluding this stage, a larger gathering was organized to present these prioritized issues to the broader community and garner support for their strategic solutions. The third stage involves executing these strategies while developing a monitoring strategy. The final stage entails a thorough evaluation of the entire meeting cycle. While focused on specific topics, these meetings utilize storytelling and interactive activities to facilitate discussions about challenges and solutions.

Figure 5: The four-phase action cycle that defines the PLA methodology (Colbourn et al., 2013).

The strategies that the groups come up with can be varied, but many of them are also shared. The report discusses potential mechanisms and strategies in more detail (See Plausible underlying mechanism section).

The philosophy behind PLA-MNH is different from traditional global health interventions. The genesis of the women's group approach is rooted in a dedication to involving people in their healthcare, a principle reinforced by the Alma Ata declaration (Rifkin, 2018). It also incorporates insights from Paulo Freire's work, emphasizing that many health issues stem from a lack of power and agency. His approach suggests that health education is more effective when it encourages dialogue and problem-solving instead of merely transmitting messages. This method facilitates communities in developing a critical consciousness to recognize and tackle the social and political factors influencing health (Morrison et al., 2019). For instance, in contexts where gender inequality hinders maternal health improvements, empowered groups can help women make informed decisions about their prenatal diet and encourage them to seek external advice or care.

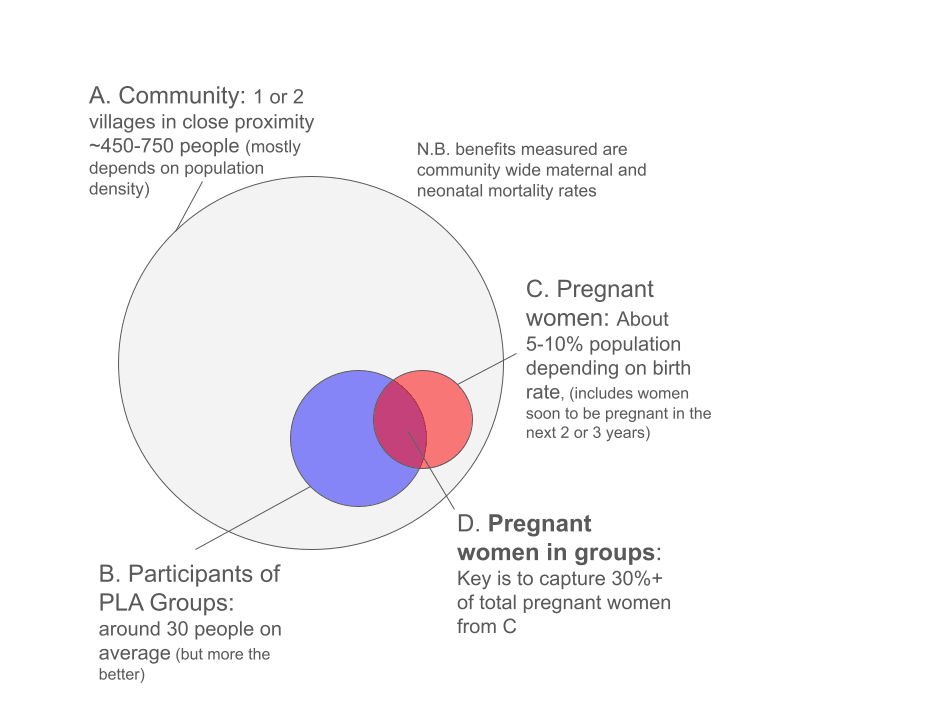

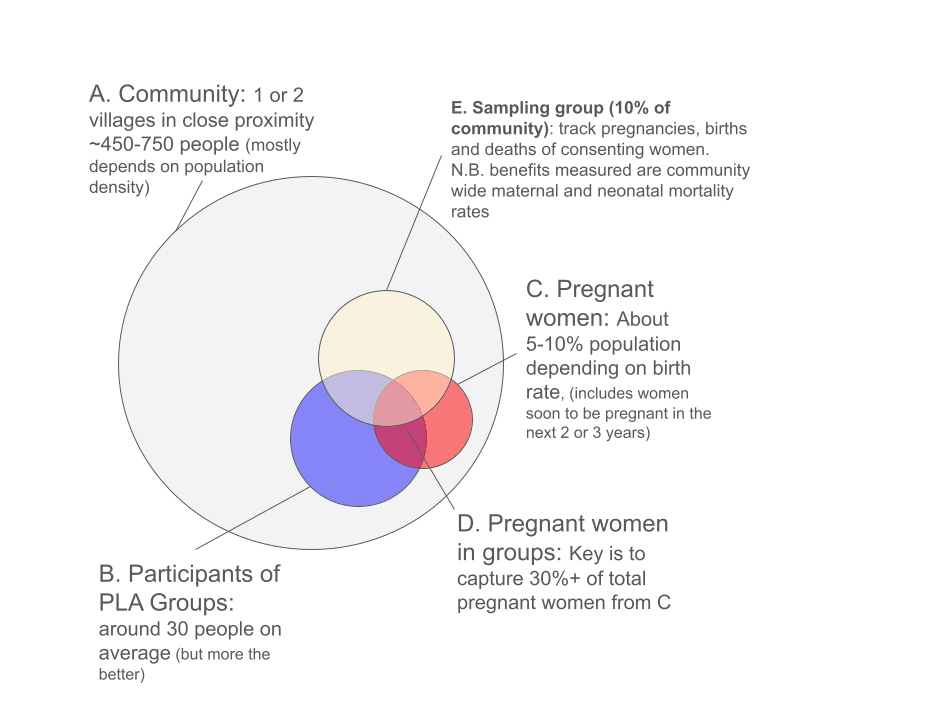

Evidence strongly supports the effectiveness of PLA groups in reducing maternal and neonatal mortality. A meta-analysis of seven randomized controlled trials (RCTs) indicates that PLA is a cost-effective method to enhance newborn and maternal survival (Prost et al., 2013). The critical predictor of effectiveness is the proportion of pregnant (or soon-to-be pregnant) women in the community captured by the groups - this should be at least 30%.

In light of this evidence, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommended PLA in 2014 – mainly for rural areas with limited healthcare access. PLA for MNH is recognized as the foremost community mobilization approach for MNH globally and is the only one specifically endorsed by the WHO and included in the Every Newborn Action Plan (WHO, 2014).

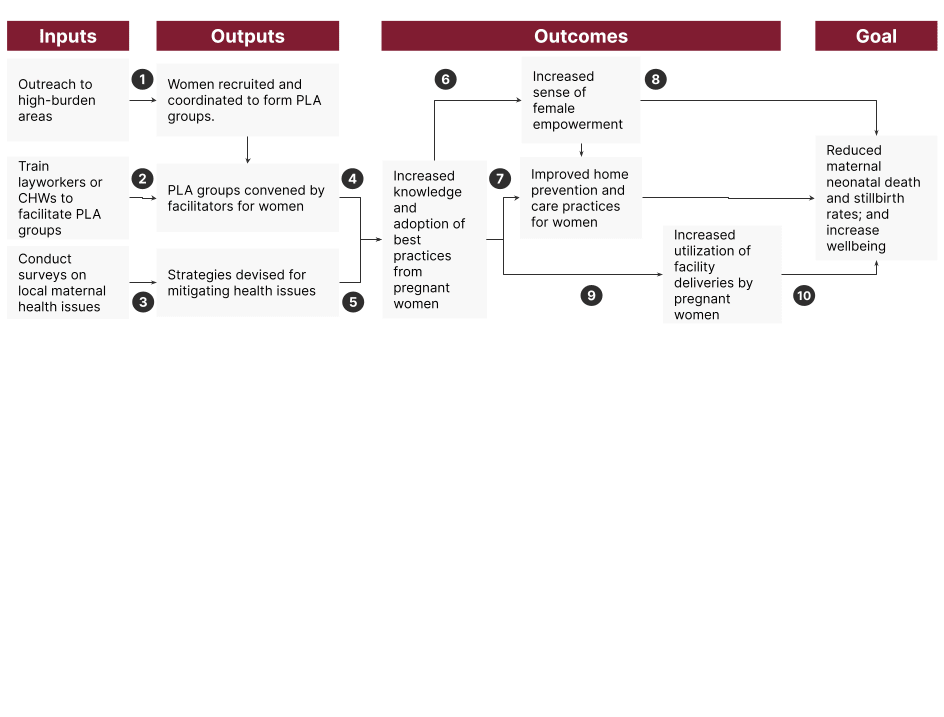

3 Theories of change

Direct implementation through community lay workers seems to be the most promising approach for a nonprofit. WCF is well established and provides technical assistance to governments and implementing partners. They seem to be limited by the lack of implementation partners that could take this to scale and would be willing to work closely with and support this new charity.

There are two broad approaches that a non-profit could feasibly take to implement PLA groups for women:

- Direct delivery and implementation: This approach involves directly supporting a network of community health workers (CHWs) or lay workers to run and facilitate the PLA groups with women. The non-profit would also be responsible for contacting and recruiting women to join the PLA groups and helping devise strategies to mitigate maternal health issues.

- Technical assistance to government or implementation partners: Similar to consulting, the non-profit could provide implementation support to governments and implementing NGOs. This role is primarily filled by WCF already. As the de facto pioneers of the intervention, they have much more expertise to provide technical assistance. Their main bottleneck to scaling PLA is the lack of implementation partners with the capacity to scale (see Expert Views section).

We think that direct delivery and implementation is a more compelling theory of change for a new non-profit because of WCF’s well-established position in providing technical assistance. The following is the detailed theory of change (ToC) for this idea:

- Women are willing to join and participate in PLA groups, and enough pregnant women are recruited to make it cost-effective.

- There are enough CHWs or lay workers in the area, and they are willing and have the capacity to facilitate the groups.

- There are many maternal health issues, and communities can devise strategies to mitigate them.

- The PLA groups are effective at increasing knowledge and changing behavior

- Women are receptive to the mitigation strategies.

- Women feel empowered as a result of increased knowledge and PLA groups.

- The strategies devised are effective at reducing maternal and neonatal mortality, including improved care at home pre, during and after pregnancy.

- An increased sense of female empowerment leads to a greater sense of well-being.

- PLA groups increase care-seeking behavior and lead to increased utilization of antenatal clinics and facility deliveries. There are also available facilities nearby that women can reach.

- Increased use of antenatal clinics and facility deliveries reduces maternal and neonatal mortality.

Community health workers vs lay workers vs volunteers

PLA has been trialed with multiple facilitator models. Generally, they have been CHWs, lay workers, or volunteers. WCF suggests that the decision would depend on many factors and that they would work with the new charity to find the optimal model.

Table 2: The various considerations when choosing the delivery platform.

| Platform | Explanation | Trust-base | Relative Costs | Number of groups each | Traveling | Reliability |

| Community Health workers | Health workers that visit communities and spread health messaging or provide healthcare services. They usually have medical-related degrees or formal training. They are usually paid by the government health system or NGOs. | Credentialed health workers | High | ~10 (includes slack) | High | High |

| Lay workers | Local literate women who receive basic training from the new CE charity to do essential health support. They are paid, and they will likely not have formal degrees. | As local community members | Moderate | 2-3 | Low | Moderate |

| Volunteers | Any local person who is willing to facilitate the meetings for free | As local community members | Low | 1 | Low | Low |

We think that the decision of which facilitator model to use is context-dependent. However, we recommend that, in most cases, the new charity use paid lay workers. This is because the one example of this intervention being implemented at a large scale (in India) uses Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHA), which are essentially government-paid lay workers who promote health messaging (see evidence section). Additionally, they would be lower cost because they do not have professional degrees, and CHWs are likely capacity-constrained already. We also think that the charity would have better control of the quality of implementation if they paid and trained them directly rather than using government-paid workers. It is important for the charity to remain open-minded to local contexts and design the optimal model.

The facilitator needs to be trusted by the community. This trust can come from their status as a trained health worker or familiarity as a community member. This means that CHWs are better suited to serve multiple communities, while lay workers should only be hired from the community they serve. The nonprofit should consider the availability and capacity of CHWs, as well as how close together each catchment area is – facilitators are generally advised to be within a 1-hour travel distance from the groups.

Utilizing volunteers may lower costs but limit the scalability and effectiveness of the intervention. Some studies have utilized volunteers, instead of paid workers, to facilitate PLA groups. While this approach would incur lower costs, we think utilizing paid lay workers or CHWs may be more scalable and allow the nonprofit to have more control over the consistency and quality of the intervention. Volunteers would be less reliable at scale, which may affect implementation quality. For example, Strongminds, which runs group cognitive behavior therapy sessions, ended its volunteer program. The exception to this may be some countries have community health volunteers that are recognised officially within the healthcare system, like CHVs in Malawi. However, we have not done enough research to be confident of this, and we think founders of such a non-profit should keep in mind opportunities that lower costs.

WCF is also piloting radio-based PLA, where facilitators are not necessary. However, the evidence base for their effectiveness is still developing, and we recommend that charities consider this option only if facilitators are unavailable.

Training facilitators

The details of what facilitator training looks like are discussed in the Annex. In brief, the facilitators generally undergo a multi-day in-class training, predominately role-playing exercises rather than theory-based. This aims to equip facilitators with the situational awareness and experience of mediating group discussions. There is a potential to scale the training via on-the-job training, essentially shadowing other trained facilitators.

We think that some additional health intervention theory would be beneficial. Although this was not included in the studies and evidence base, we suspect that equipping the facilitators with knowledge of basic, well-evidenced interventions would lead to even greater effects. For example, interventions such as exclusive breastfeeding, keeping the baby warm, or skin-to-skin contact should be beneficial in almost all contexts. While we think the PLA approach of empowering and trusting the communities to find their solutions should be the primary focus, we think communities could also benefit from slight guidance on proven strategies.

4 Quality of evidence

4.1 Evidence that a charity can make a change in this space

WCF is the main stakeholder and NGO operating in the space. Established in 2001 as a collaborative effort of academic researchers from University College London (UCL), it plays a pivotal role as an NGO stakeholder in community mobilization approaches to reduce maternal and neonatal mortality. Initially formed by UCL researchers, WCF has evolved into an independent non-governmental organization. Despite its separation from UCL, WCF maintains a collaborative relationship with the university, particularly in implementing interventions within research trials. PLA is WCF’s most notable innovation and was developed in partnership with UCL and various in-country partner NGOs (Rosato & Drazdzewska, 2021).

Evidence indicates that both governments and NGOs can effectively implement the intervention. As detailed in the subsequent Evidence section, at least eight trials, including a government-led scaled intervention, have reported successful outcomes.

Recently, GiveWell provided Spark Microgrants (Spark) with a scoping grant to develop a proposal for a PLA pilot program.

By analogy, PLA as an intervention is also quite similar to group-based cognitive behavioral therapy for treating mental health disorders. Organizations like StrongMinds and Vida Plena (the latter we previously incubated) have shown that such delivery models are tractable and cost-effective (McGuire & Plant, 2021).

4.2 Evidence that the change has the expected health effects

More than 49 peer-reviewed studies on PLA for MNH exist. We have not read all of this literature in detail, but this section summarises the most relevant findings that we have read.

Strong evidence supports the effectiveness of PLA in reducing neonatal and maternal mortality. This is evidenced by a meta-analysis conducted by Prost et al. (2013), which included seven trials involving approximately 119,000 births, complemented by an additional trial with around 7,200 births published post-meta-analysis (Tripathy et al., 2016). Key points from these studies include:

- Prost et al. (2013) demonstrated that participation in women’s groups significantly reduced neonatal mortality by 20%. While a 23% reduction in maternal mortality was noted, the outcome variability rendered this finding statistically non-significant.

- The participation rate of pregnant women seems crucial, with studies that achieve over 30% participation rates (4 studies) having significant reductions in community-wide neonatal mortality by 33% and maternal mortality by 49%.

- We found it confusing to interpret these results, so to clarify, we attempt to illustrate these results in Figure 6 below.

- We think a possible way to interpret this result is that it is likely that in the studies where the participation rates were below 30%, the effect of the intervention was too small to detect rather than having no effect.

- Tripathy et al., (2016) largely corroborated the meta-analysis findings, confirming the efficacy of PLA-MNH.

- Most of these trials had “Health service strengthening” as control arms. PLA was compared against other interventions, such as training health workers and traditional birth attendants, AND/OR equipment given to health facilities and CHWs. This suggests that the effect sizes reported would be even greater when compared to no intervention controls. We recommend looking at Table 1 in Prost et al. (2013) for more details.

- Most of these trials and the meta-analysis were supported by WCF and UCL, and we have slight concerns regarding the risk of bias. However, we consider the evidence sufficiently strong and the studies sufficiently high quality.

- In addition, a pre-post quasi-experimental study looked at women’s SHGs, increased contraceptive use, institutional deliveries, initiated timely and exclusive breastfeeding and provided age-appropriate immunization (Saggurti et al., 2018).

- An economic analysis based on one of the above RCTs in the meta-analysis yielded a cost-effectiveness of $83 per DALYs averted (Sinha et al., 2017).

Note: The key point is that by capturing at least 30% of all pregnancies, the intervention achieves measurable mortality reductions for all the pregnancies in the community, not just among group member pregnancies.

Based on the meta-analysis findings, the WHO recommends implementing PLA in rural areas with high maternal and neonatal mortality rates and limited access to services (WHO, 2014). Furthermore, PLA is incorporated into the Every Newborn Action Plan, an initiative spearheaded by WHO and UNICEF.

However, evidence regarding post-neonatal child mortality (ages 1-5) is less conclusive. A follow-up study in Nepal by Heys et al. (2018) identified non-significant reductions in post-neonatal odds of child deaths (OR 0.70 95% CI 0.43 to 1.18) and disability (0.64 95% CI 0.39 to 1.06).

Moderate evidence supports the scalability of the intervention. Nair et al. (2021) executed a cluster RCT of a government-scaled version of PLA-MNH in Eastern India, achieving similar reductions in neonatal mortality by 24% over 24 months. The intervention leverages frontline lay workers called ASHAs, covering 1.6 million live births. Twenty of the 24 districts achieved adequate meeting coverage and quality. In those 20 districts, the intervention was estimated to save the lives of ~12,000 newborns over 42 months. The incremental cost per neonatal death averted was $1,272 (Haghparast-Bidgoli et al., 2023).

There is weak evidence of possible spillover effects, where behavior changes were noted in both attendees and non-attendees within intervention areas, suggesting broader impact potential. This is potentially attributed to sharing healthcare information among community members, though this remains speculative.

There is weak evidence suggests the effects may be long-term. An RCT in Nepal observed that 80% of PLA groups continued to convene two years after the cessation of external support for the intervention (Sondaal et al., 2019).

Broadly speaking, there is also moderately strong evidence supporting the effectiveness of community-based interventions in reducing maternal and neonatal mortality. A Cochrane review analyzing various community-based strategies such as home visitation, home-based care, and PLA has found significant benefits across multiple health outcomes. These include reductions in neonatal mortality, maternal morbidity, stillbirths, and perinatal mortality (Lassi & Bhutta, 2015; Bhutta et al., 2005).

There is weak evidence for positive externalities.

- The research conducted in India also revealed that the initiative not only had an impact on physical health but also on mental health, leading to a 57% decrease in the incidence of maternal depression (Tripathy et al., 2010). However, they measured depression in years 2, 3, and an average of both. Year 3 was the only significant year, which is a bit suspect despite the large effect size.

- Malde and Vera-Hernández (2022) noted that households in PLA-treated communities, compared to untreated communities, were able to compensate for crop loss through community informal risk-sharing mechanisms (i.e., community insurance)

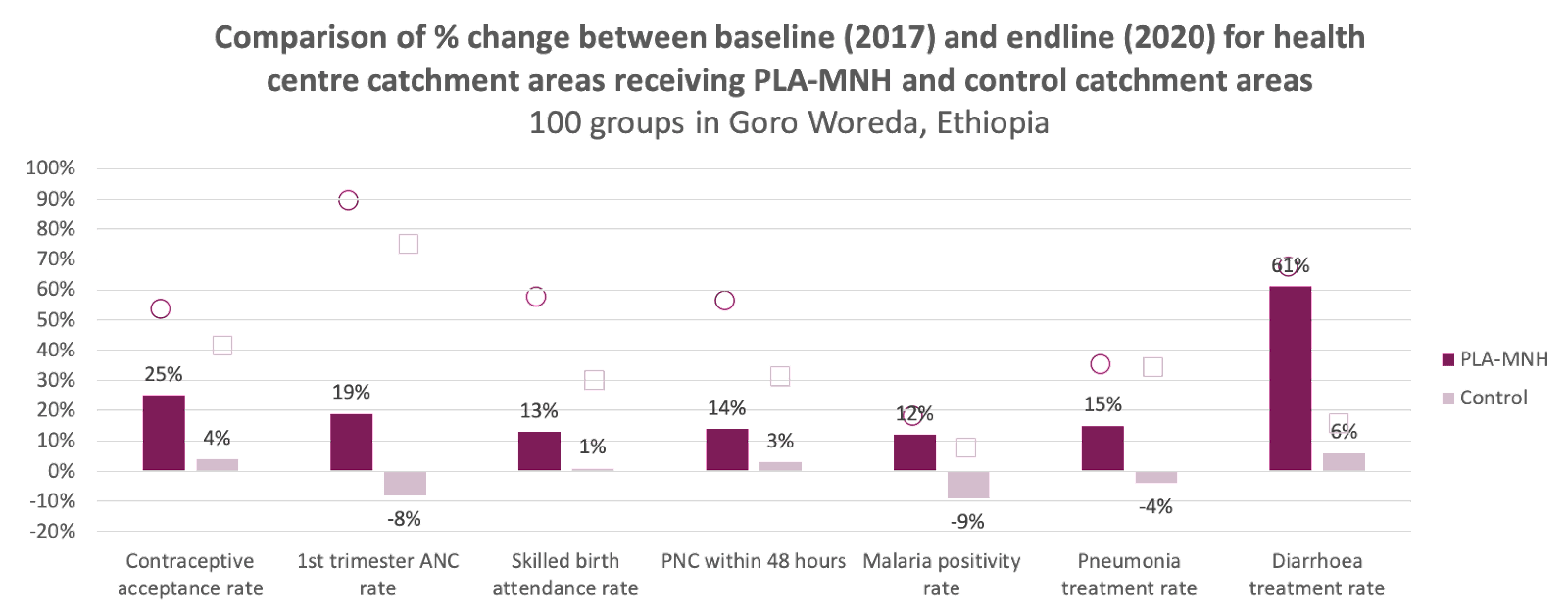

- According to WCF’s website, their partner, Doctors with Africa CUAMM, has successfully established 100 PLA groups in Ethiopia. In addition to increasing healthy birth behaviors, there is weak evidence that PLA increased the contraceptive acceptance rate (WCF, 2022).

- Furthermore, PLA may contribute to reducing inequality. For instance, a meta-analysis of four PLA studies found that PLA can lead to equitable reductions in neonatal mortality across various socio-economic groups (Houweling et al., 2016).

We also found weak evidence that PLA groups can be adapted to other domains. There were positive outcomes measured for the following areas:

- Antimicrobial resistance (Cai et al., 2022).

- Contraceptive use (Saggurti et al., 2018)

- Violence against women (Nair et al., 2020; Chakraborty et al., 2020)

- Childhood and maternal nutrition (Kadiyala et al., 2021)

- Diabetes (Fottrell et al., 2019)

- Interestingly, this paper was a three-arm RCT that also looked at mHealth mobile phone messaging and found that the PLA arm had a 20% reduction in diabetes. In contrast, mobile messaging had no significant effect compared to control.

This suggests that the groups can be later repurposed for other domains, as the framework for problem-solving applies to most issues.

Analogy: Evidence for self-help groups

There is extensive literature looking at the effectiveness of different types of SHGss on different types of physical or mental disabilities. As mentioned, PLA is a specific type of SHG, emphasizing the four-phase action cycle. Thus, the evidence for PLA described in the previous section exists narrowly within the broader evidence base for SHGs.

Table 3: A non-exhaustive list of meta-analyses and systematic reviews on various SHG interventions.

| Study | Description of SHG intervention | Effects |

| (Smith-Turchyn et al., 2016) | Group-based Self-management Programmes to Improve Physical and Psychological Outcomes in Patients with Cancer | Six trials were included: Group-based self-management programs were found to improve physical function [standard mean difference (95% confidence interval) = 0.34 (0.02, 0.65), P = 0.04] but no significant results were found between groups for quality of life [0.48 (-0.16, 1.11), P = 0.14] and physical activity level [0.21 (-0.07, 0.5), P = 0.15] outcomes. |

| (Gugerty et al., 2019) | Self-help groups in any domain from papers between 2004-2014 | The authors categorized outcomes into “positive”, “mixed” and “negative” or “not significant”.

There was a lot of positive evidence for financial outcomes (23 studies), i.e., savings groups and loan facilitation, where SHGs were mostly positive.

Evidence for reproductive health and HIV outcomes were mostly positive (10 studies). The most supported outcome was for increased knowledge and use of contraceptives.

There was also positive evidence for agriculture outcomes (10 studies), like technology adoption and agricultural output/yields.

Positive evidence supported empowerment outcomes (24 studies), like self-efficacy, control over decision-making, or participation in government and other community groups.

Note: The authors summarised PLA for MNH (16 studies) as having the most substantial evidence base and having the most positive association between SHG delivery and outcomes. |

| (Brunelli et al., 2016) | Social Support Group Interventions for Psychosocial Outcomes | Nineteen studies and ~3000 participants were examined. Mostly positive outcomes. |

| (Newham et al., 2017) | Self-management interventions (SMI) for people with COPD | SMI improved patients' quality of life and reduced emergency department visits. |

External validity concerns

We have uncertainty and concerns about the external validity of the intervention.

- Most studies were conducted in South Asia, raising questions about the applicability of PLA-MNH in sub-Saharan Africa due to cultural differences. However, higher neonatal and maternal mortality rates in these regions could compensate for these cultural disparities.

However, there is weak to moderate evidence suggesting the intervention would work in sub-Saharan Africa.

- Relative to other RCTs in the meta-analysis from Prost et al. (2013), the RCT from Malawi showed the largest effect size on neonatal mortality and the second largest on maternal mortality, suggesting broader applicability to SSA.

- Supporting evidence from a qualitative study in Uganda (Belaid et al., 2021) indicates that PLA can effectively alter the behaviors of women, pointing to potential success in other sub-Saharan countries.

- An observational study in Tanzania also suggested that 95% of groups experienced increased maternal health knowledge and positive behavior changes among healthcare workers (Solnes Miltenburg et al., 2019).

- There is unpublished data, Figure 7, of a trial funded by the Gates Foundation Comic Relief in Ethiopia, having many positive effects on beneficial health behaviors (WCF, 2022).

- If this replicates, the contraceptive uptake shift alone could be highly cost-effective, averting unintended pregnancies that could lead to maternal and neonatal death and unsafe abortions.

Plausible underlying mechanisms

The mechanisms underlying the mortality reductions from PLA are not entirely clear:

- The intervention is believed to influence the behavior of pregnant individuals and/or birth attendants. Analysis of trial data showed that PLA-MNH altered home care and delivery practices, such as using safe delivery kits and improved hygiene practices (Seward et al., 2017).

- According to the meta-analysis: “In three of four South Asian trials in which the behavioral mechanisms were reported, women's groups showed strong (including significant and non-significant) effects on clean delivery practices for home deliveries (especially handwashing and use of clean delivery kits) and noticeable effects on breastfeeding. The use of women's groups resulted in significant increases in the uptake of antenatal care in two studies and institutional deliveries in one study. The largest behavioral effects on mortality seen in the South Asian studies are likely to have been determined by changes in clean delivery practices for home deliveries and improved immediate postnatal care at home.”

- This is supported by a later published scaled-up version, where authors noted that exclusive breastfeeding and early infant wiping rates increased, as well as improvements in essential newborn care practices (Nair et al., 2021).

- However, there was substantial variability among trials regarding which health behaviors improved, with increases ranging from 0 to 35 percentage points.

- No consistent improvements were noted in antenatal care uptake, facility delivery, breastfeeding initiation, or exclusive breastfeeding for six weeks post-delivery, although some individual trials reported gains in these areas.

- The likelihood that effects result from enhanced home-care solutions rather than professional care-seeking lends credibility to the intervention's applicability in sub-Saharan Africa, where professional care quality is generally lower.

- Experts also mention several solutions that the groups consistently develop, for example, pooling community funds into an emergency fund, community bicycle ambulance services, and community-based health campaigns.

Although it is important to understand the mechanism behind the intervention, we think the measured effects of endline outcomes are more important. There are many plausible mechanisms for mortality reductions, and it would make sense to expect different mechanisms for different communities depending on their localized context. To some extent, the charity would have to trust the participants to solve the issues they are most familiar with. We have written more on the case for empowering and trusting beneficiaries in the Annex.

5 Expert views

GiveWell

Generally, GiveWell thinks that interventions in MNH can be very cost-effective. However, they caveat that there is a lot of variability in terms of quality of implementation.

GiveWell would be excited to consider new charities implementing PLA groups for women. They have done initial research and think that the intervention is promising but have struggled to find organizations that can implement it at sufficiently low costs (in order to meet GiveWell’s cost-effectiveness threshold). GiveWell has spoken to WCF previously, and they are focused on technical assistance work, so they are still looking for implementation partners.

They previously gave a scoping grant to a potential implementation partner, Spark to explore this intervention.

Their biggest uncertainties revolve around the costs of the implementation. They mentioned that group size is a key moderator of effect sizes. Above a certain catchment area threshold, the effect sizes take a hit. In some cases, the size of target areas has to increase to reduce costs, which would reduce the impact estimates.

GiveWell is not entirely certain why it is so difficult to find implementation partners for the program. They think it has something to do with how non-traditional the program is – it is not as simple as delivering a commodity or manualized training. Rather, it is more about facilitation and finding the right people within a given catchment area and then delivering good facilitation by trusted people.

Women and Children First

WCF is excited for a new entity to work in the space and scale PLA-MNH. If it exists, WCF is eager to collaborate and work with this new charity.

WCF positions itself in a technical advisory role. They are eager to support and train implementation partners, preferably local NGOs. Finding local NGOs with the capacity to implement PLA at scale has been challenging - it requires competency in managing a large workforce of facilitators spread out over a large geographical region.

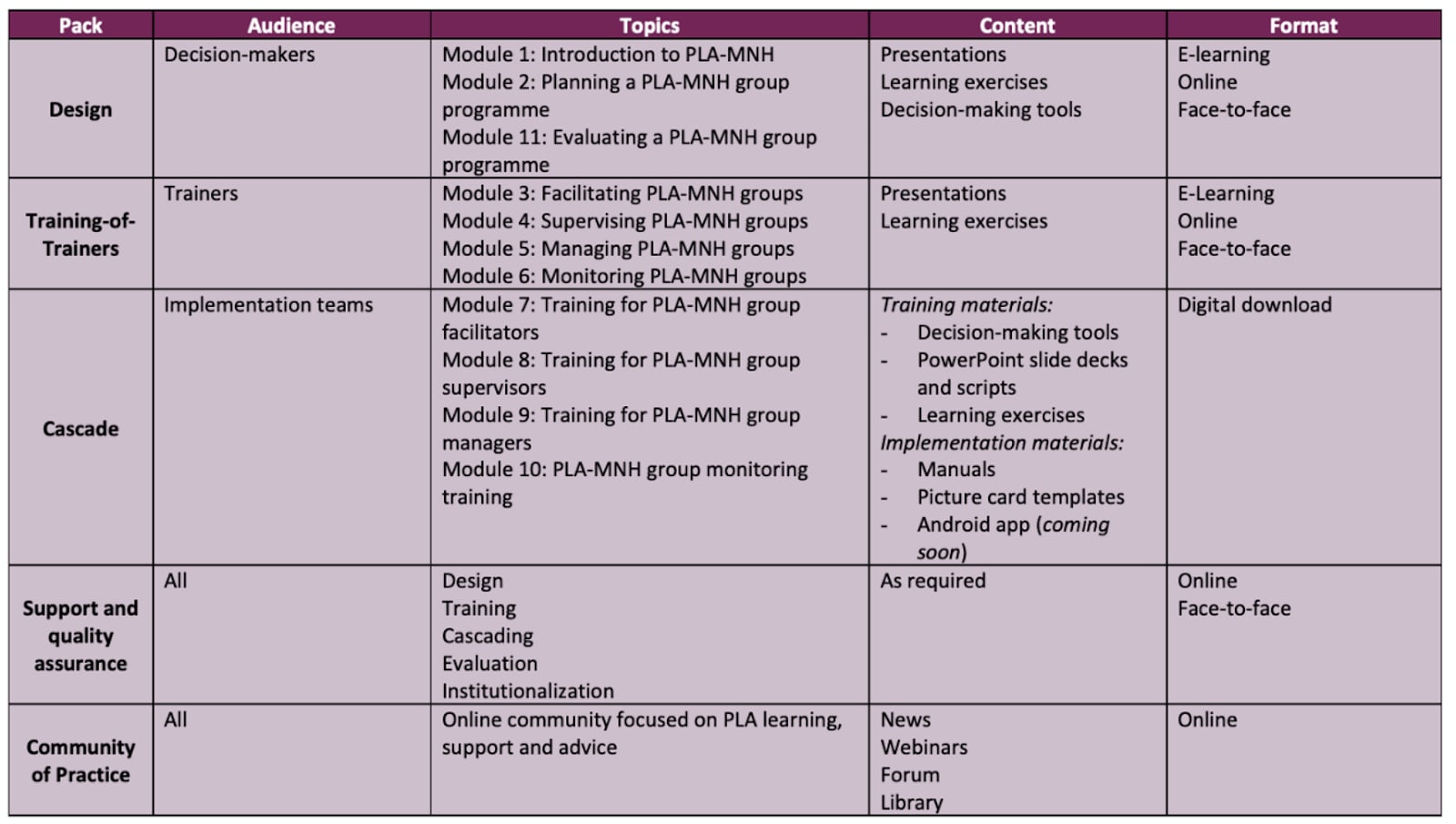

Figure 8: This is the technical assistance package WCF offers organizations to help them embed PLA from their website.

WCF also sees a potential role for a new organization based in LMICs to serve an advocacy and coordination role. WCF is sensitive to the cultural aspects and power dynamics and prefers that there is an LMIC partner to support the work.

Three pillars enable the country-scaling of PLA: 1. government alignment, 2. funding, and 3. implementation partners. It is preferable for sustainability for the government health system to take over operations once an NGO has set up early implementation.

WCF is location agnostic and willing to support any country, provided the three pillars are met. Beyond Ethiopia, Tanzania, and Malawi, they have begun discussions to work in Sierra Leone with Partners in Health. Their Tanzania work, in partnership with UNICEF, is currently halted due to funding constraints. They have established a strong partnership with Amref Health to deliver PLA in Uganda.

The design of the implementation is context-dependent. Local contexts determine design choices, such as whether the facilitators are CHWs, lay workers, or health volunteers. Trust in the facilitator by the community is important, but this can come from several sources – either a health professional background or a person from the local community could work.

There are indications that the intervention is more cost-effective at scale. In India, where they have implemented PLA at scale, the costs per group at scale were 10x lower, while the effectiveness was only reduced from 33% to 24%. The program is now being handed over to the government for sustained implementation.

Logistical challenges commonly dictate choices – including whether there are enough CHWs and whether they are capacity-constrained. It is recommended that facilitators be located within 1-hour travel distance from group locations.

While it is important to target pregnant women, it is also important to have other members of the community involved. The recommendation is to capture at least 30% of the total pregnant women in the community. However, other community members are important in being involved in the solutions, too. Hence, the costs ideally scale with the number of groups and not the number of participants; in other words, it is better to have more people in a group, which would maximize the likelihood of capturing more pregnant women as well as community members who provide solutions.

The average group size is around 30 people, and the average population in a catchment area per group is around 450-700 people (sometimes up to 1000 people). Facilitators usually require eight days of training, and supervisors require 10-12 days of training. Training is usually in a role-playing, situational style – traditionally done in the classroom- but there are also examples of effective on-the-job shadowing.

Facilitators are not group leaders. Stress that they are not teachers. Groups usually elect a committee with a chairperson, treasurer, secretary, etc. PLA is a very hands-off approach, and the facilitators are just there to mediate.

There are some solutions and strategies that are common to groups. For example, community funds can be pooled into an emergency fund, community bicycle ambulance services, and community-based health campaigns.

There are no published studies on radio-based PLA yet. WCF is keen to work with partners to establish a better evidence base. The benefit is that it bypasses logistical barriers where facilitators are not available.

Funding is challenging, especially from governments that already have other community-based programs set up and do not see the need to add more. Community health systems can be challenging for governments to manage at the grassroots level. Often, there will not be a widely used evidence-based guide or toolset for community health volunteers to follow - PLA could offer them a simple and effective way of engaging communities to improve health outcomes. However, large philanthropic funders have shown interest. Gates Foundation has funded Amref's and JSI's work in Ethiopia. Moreover, GiveWell is interested.

6 Geographic assessment

The geographic assessment was done in two stages. First, we looked at where existing organizations are working or have worked. This information was used as input in the formal geographic assessment to measure how much attention an issue is being paid. Second, we conducted a formal geographic assessment to find the top priority countries for starting a new nonprofit.

6.1 Where existing organizations work

WCF is the main player in the space, and they mostly provide technical assistance to governments and implementation partners. According to their website, they have operated in 15 countries in Africa, Asia, and Central America. However, according to their 2022-2024 strategy document, their main focus in the next two years will be in Ethiopia, Malawi, and Tanzania.

In their 2021 interview with GiveWell, they have listed the following as implementation partners:

- Ekjut (India)

- Diabetic Association of Bangladesh - Perinatal Care Project (BADAS-PCP, Bangladesh)

- MaiMwana Project (Malawi)

- MaiKhanda Project (Malawi)

- Mother and Infant Research Initiative (MIRA, Nepal)

- The Society for Nutrition, Education, Health and Action (SNEHA, India)

An advantage of PLA is that very few organizations except for WCF are focused on it, and hence, the chances that it is neglected are much higher.

The broader MNH space has many non-profits. As experts mentioned, this is a crowded space; however, they tend to work on many different interventions. As a result, it is challenging to assess how well-covered a space is and whether there are still any gaps.

Some organizations like the WHO and UNICEF operate in so many countries that we decided not to include them in the analysis for country-neglectedness. The organizations that we identified and mapped out are the following:

- Jhpiego: An international, non-profit health organization affiliated with Johns Hopkins University, Jhpiego focuses on improving healthcare services for women and families, particularly in maternal and child health, HIV/AIDS, and reproductive health.

- The Clinton Health Access Initiative (CHAI): A global health organization committed to saving lives and reducing the burden of disease in low- and middle-income countries. They focus on improving access to and the quality of healthcare services, strengthening health systems, and addressing critical issues like HIV/AIDS, malaria, tuberculosis, and maternal and child health.

- IntraHealth International: This non-profit organization specializes in improving health care in developing countries, focusing on strengthening health workers and the systems that support them.

- Maternity Foundation: A Danish organization, Maternity Foundation works globally to reduce maternal and child mortality in low-resource settings through mobile health solutions and capacity building.

- Maternity Worldwide: Operating internationally, Maternity Worldwide focuses on providing access to quality maternal healthcare, aiming to reduce maternal and newborn mortality and morbidity in low-income countries.

- Partners in Health: This global health organization strives to provide a preferential option for the poor in health care, working in close partnership with local governments to deliver high-quality health care and address the root causes of illness.

- Every Mother Counts: An advocacy and mobilization campaign, Every Mother Counts focuses on making pregnancy and childbirth safe for every mother, highlighting maternal health challenges and solutions.

- EngenderHealth: EngenderHealth is an international reproductive health organization working to improve the quality of health care in the world's poorest communities, with a focus on reproductive rights and gender equality.

- Healthy Newborn Network Partners: This network collaborates with various organizations to improve newborn health globally, focusing on advocacy, knowledge management, and providing technical support to address neonatal mortality and morbidity.

- Pronto International: Pronto International specializes in developing and implementing innovative, interactive training strategies for healthcare providers around the world, focusing on obstetric and neonatal emergency care.

The detailed mapping of the countries they work in can be found in our geographic assessment. This is not an exhaustive list, and it is beyond the scope of this report to map all of them.

6.2 Geographic assessment

We conducted a geographic assessment, which is basically a weighted factor model comprising scale, neglectedness, and tractability metrics for each country. The geographic assessment was adapted from another one that looked at Basic Emergency Obstetric and Newborn Care (BEmONC) access. Identifying PLA-specific metrics to tailor the geographic assessment was challenging – the most suitable was the number of CHWs per 1000 people. However, this dataset from the World Bank was very outdated.

Scale

The scale is the largest component of the model, comprising ~57% of the total weighted score. We want to prioritize the countries with a sufficient population with the highest burden. We take into account the following:

- Maternal mortality rate

- Neonatal mortality rate

- Total population

- Birth rate

- DALYs lost per 100,000 people due to maternal disorders

- DALYs lost per 100,000 people due to neonatal disorders

Neglectedness

The neglectedness category aims to provide an indication of how much resources are devoted to fixing the problem. It comprises 20% of the total weighted score. We take into account the following:

- Number of organizations working here

- Health Access and Quality Index 2015 (IHME)

- GNI PPP, 2022 (current dollars)

- Current health expenditure (CHE) as a percentage of GDP

- Domestic general government health expenditure (% of GDP)

- Domestic general government health expenditure (% of current health expenditure)

All of these metrics were inverted to provide an indication of the lack of resources and attention going to those countries.

Tractability

The tractability category aims to provide an indication of how easy it is to work in the countries and, if successful, how easy it is for women to access healthcare and follow through with desired behavior changes. It comprises 23% of the total weighted score. We take into account the following:

- Share of Births Attended by Skilled Health Staff (%)

- Nurses and midwives (per 1,000 people)

- CHWs (per 1,000 people)

- Access to sexual and reproductive health care, 2022

- Fragile States Index (2022) Corruption Perceptions Index (2021)

- WJP Rule of Law Index (2022)

- Freedom in the World (2022)

Despite a high need, we ruled out some countries, such as Somalia, South Sudan, Chad, and Mali, because of the infeasibility of operating PLA groups in conflict zones.

Based on this weighted model, the top countries we identified that were most promising are as follows:

| Country | Weighted average |

| Sierra Leone* | 1.194 |

| Nigeria | 1.116 |

| Guinea | 1.042 |

| Benin | 1.017 |

| Côte d'Ivoire | 0.929 |

| Pakistan | 0.928 |

| Guinea-Bissau | 0.919 |

* Note that WCF has begun a partnership with Partners in Health in Sierra Leone, it’s unclear what scale they will implement PLA at.

7 Cost-effectiveness analysis

We have modeled the cost-effectiveness of this intervention for Sierra Leone, Nigeria, and Guinea. These were chosen as they are top options in the geographic assessment. A driver tree outlining the structure of the model can be found here. The charity was modeled as operating for 17 years (unless it cannot establish itself and shuts down after ~3.5). Extending this further would only have a modest effect on the final result.

Note: We produced the model before we decided that lay workers would be more promising than CHWs. Hence, the model uses CHWs. We do not expect the cost-effectiveness to be drastically different because of this.

We also produced the model before we learned that WCF is working with Partners in Health in Sierra Leone.

7.1 Costs

We modeled the intervention as having three types of charity costs:

- Fixed HQ costs: This would include co-founder salaries and any additional staff that provides operations management, program management, fundraising, finance, and HR. It would also cover costs like flights, software, conference fees, and third-party implementation partner support on content creation and translation.

- Training costs (variable): Recruiting and training facilitators to run the PLA groups and training supervisors who train and manage the facilitators. We modeled the training process for supervisors and facilitators occurring away from home, so travel stipends are needed to cover transport, food, and accommodation. These stipends make up the majority of the training costs.

- PLA operating costs (variable): This is the cost to run the Participatory Learning and Action groups, which is made up of (a) the salary of the facilitators, their supervisors and the program managers, (b) transport costs for the facilitators to travel by motorcycle taxi an average of 1.5 hours per day to and from a nearby village to run sessions, (c) a cost to recruit local community members to participate in the groups, e.g. door-to-door advertising or providing non-monetary incentives.

Table 4: Cost breakdown by type for different countries (based on point estimates, not Monte Carlo analysis)

| Country | Fixed HQ costs | Training costs (variable) | PLA operating costs (variable) | PLA operating costs per participant per yr (variable) |

| Sierra Leone | 51.4% | 0.6% | 47.3% | $5.16 |

| Nigeria | 18.6% | 1.35% | 79.8% | $5.97 |

| Guinea | 36.8% | 0.8% | 61.9% | $8.91 |

We modeled facilitators working full-time on a salary basis. In this model, (a) training costs turned out to be very low compared to operating costs (i.e., ~1% as much), and (b) transport costs accounted for ~60% of operating costs. This suggests that cost-effectiveness could be increased significantly by increasing training costs to reduce transport costs: The charity could hire many more facilitators who work part-time and just serve villages close to where they live.

We modeled training CHWs to facilitate the groups instead of hiring people without a background in health care (which was the norm among PLA interventions in the literature).

7.2 Effects

We modeled four health benefits: 1. Reduced maternal mortality, 2. Reduced neonatal mortality, 3. Reduced incidence of stillbirths, 4. Reduced child mortality. The first three benefits were modeled using effect sizes from Prost et al. (2013) meta-analysis, while the fourth was modeled using Heys et al. (2018).

For each health benefit, the magnitude of the benefit (in DALYs per population per year) was calculated as the product of the baseline incidence (e.g., maternal deaths per live birth), the effect size of the intervention (e.g., % reduction in maternal deaths per live birth), the DALY coefficient (e.g., DALYs lost per maternal death) and the birth rate (births per population per year). Note that the DALY coefficient depends on some subjective value judgments, which users can adjust to match their values. We have used GiveWell’s coefficients to allow for like-for-like comparisons with GiveWell cost-effectiveness estimates for different interventions.

There are some idiosyncracies in how the effects were modeled to be aware of:

- Due to concerns relating to external validity (discussed in Section 4.2), the effect sizes were discounted significantly (20-40%).

- The effect size in the Prost et al. meta-analysis was calculated for the entire population, not just those who attended the PLA groups, even though the benefit will be strongest for pregnant women who attend the PLA groups. As a result, the effect size was a lot higher in studies where a higher proportion of the population’s pregnant women attended the groups. The study included a sub-group analysis for studies where the proportion of participating pregnant women in the population was <30% and >30%, respectively. Where available, we have used the effect size for the >30% case because a charity focused on cost-effectiveness will aim to maximize this participation rate and not operate in villages where the participation rate will be too low.

- The effect size is modeled as a fixed percentage reduction in the probability of health outcomes, regardless of how high the baseline incidence rate is for those health outcomes. We expect that when the baseline incidence rate is particularly poor, there is more low-hanging fruit that the PLA groups can address, meaning that the effect size is higher. This gives charity founders another reason to focus on geographies with higher baseline health burdens.

Several conservative assumptions were made regarding the benefits:

- The effect is modeled as applying only for as long as the intervention is run (i.e., no lasting benefits are modeled after the program ends).

- The model does not account for any increases in effect size for women who run through multiple intervention cycles.

- Other potential health benefits to children later in life and benefits to mothers from increased autonomy due to potentially increased access to family planning are not captured in this model (i.e., if they exist, they represent further upsides).

Note: This model does not include any disbenefits to beneficiaries caused by increased costs paid to access healthcare as a result of participation in PLA groups (e.g., choosing to pay for skilled birth attendants instead of untrained traditional practitioners, or choosing to travel to give birth in a healthcare facility). This is because we could not find any way to estimate these costs that did not seem entirely arbitrary. Because it is unclear exactly how PLA causes health benefits, it is unclear to what extent the benefit comes from changes that cost beneficiaries money (like traveling to seek medical care) vs. from changes that are free (like ensuring that their birth attendant washes their hands). A charity implementing this intervention should attempt to monitor the cost of healthcare seeking among participants to understand whether this meaningfully reduces the net benefit.

7.3 Scale

The model involves two numbers for scale:

- The size of the population reached (on which the benefits depend, as effect sizes apply at the population level)

- The number of participants in the PLA groups (on which variable costs depend)

We are highly uncertain about what numbers to use for both of these scale variables. It is believable that the actual numbers could be much higher or lower than what we have modeled.

The number of PLA group participants at scale was estimated top-down to be 47,000/yr for Sierra Leone, ~196,000/yr for Nigeria, and 50,000/yr for Guinea. The reason this differs between countries is that we assume that in larger countries, there are a greater number of ‘low-hanging fruit’ villages to cover. These numbers equate to reaching 10% (90% CI 2-35%) of the rural population in Sierra Leone, 2% (90% CI 1-4%) in Nigeria, and 6% (90% CI 3-12%) in Guinea. The reason this is not close to 100% is that we assume many villages will be ruled out because (a) their populations are too small to assemble a group large enough to serve cost-effectively, (b) they are too remote for facilitators to travel to cost-effectively, (c) the baseline burdens of maternal/neonatal mortality are very low, (d) the charity is not able to recruit >30% of the pregnant women in the population.

The number of participants in the PLA groups was calculated by multiplying the size of the population reached by an estimate of the proportion of the population who will participate in the groups: 100 participants per 1000 members of the population. The proportion of the population who attend the groups needs to be high enough to ensure that >30% of pregnant women in the population attend (given the importance of this for achieving the effect size in the literature). We used Monte Carlo simulations to model these (and other) uncertain values, with the upper and lower bounds being ~186-246 (assuming all women of reproductive age attend) and ~20-25 (assuming only pregnant women attend – two-thirds of them), respectively.

7.4 Results

Table 5: Modeled cost-effectiveness without <5 child mortality benefits for different countries (net present value, including the risk that the charity fails to establish the intervention)

| Country | $/DALY | Cost to save a maternal or neonatal life (not counting stillbirths) | Cost to save a life (including stillbirths) |

| Sierra Leone | $56.01 | $2,939 | $1,254 |

| Nigeria | $30.31 | $1,576 | $682 |

| Guinea | $69.94 | $3,943 | $1,511 |

Suppose we include highly uncertain benefits to <5 child mortality. The cost-effectiveness would increase as follows.

Table 6: Modeled cost-effectiveness with <5 child mortality benefits for different countries (net present value, including the risk that the charity fails to establish the intervention)

| Country | $/DALY | Cost to save a maternal or neonatal life (not counting stillbirths) | Cost to save a life (including stillbirths) |

| Sierra Leone | $39.8 | $1,821 | $994 |

| Nigeria | $21.22 | $961 | $535 |

| Guinea | $48.52 | $2,315 | $1,190 |

Note that because certain costs would need to be paid upfront (like training supervisors, training facilitators, recruiting participants) and it would take a while for participants per group, groups per facilitator, and facilitators per supervisor to grow to their maximum, cost-effectiveness would be significantly lower during the charity’s early years.

This is roughly in the ballpark of GiveWell’s preliminary cost-effectiveness estimates. They estimate the cost-effectiveness of PLA is 9.2x and 10.7x cash transfers in Sierra Leone and Nigeria, respectively. Their most cost-effective country modeled is Mali, estimated to be 12.1x cash transfers (GiveWell, 2022). In contrast, our $39.8 per DALY estimate in Sierra Leone puts it at roughly 20x cash transfers.

7.5 Location

Modeling different countries would influence the modeled cost-effectiveness as follows:

- Different baseline health burdens will change the benefit per pregnant woman reached

- Different countries have different labor costs and transport costs

- Different rural population sizes will influence the maximum scale the charity can reach, as there are more villages to choose from that may meet requirements for cost-effective operations

Meanwhile, choosing different locations would influence the actual cost-effectiveness in additional ways that will be difficult to predict and capture in an ex-ante model, for example:

- The geographic distribution of villages will dictate how many facilitators the charity needs to train and how far they need to travel to reach 1000 members of the population

- The cost to convince a sufficient number of pregnant women in the community to attend will presumably vary from country to country

8 Implementation

8.1 What does working on this idea look like?

A significant portion of the work involves recruiting and overseeing a team of facilitators responsible for conducting the PLA sessions. While the WCF provides ample training materials, considerable time must be allocated to train facilitators thoroughly.

Crucially, the non-profit should actively gather and analyze feedback from facilitators, examining recurring challenges faced by them or the participating mothers. This analysis is vital for developing strategies to support the mothers effectively.

Another key aspect is crafting a targeted outreach strategy to attract pregnant women to join the PLA groups. This strategy must be well-designed to reach and engage the intended demographic effectively.

Additionally, conducting meticulous measurement and evaluation is imperative to verify the impact of the intervention. This often involves surveying participants and healthcare facilities to gather relevant data.

There is also a need for some level of engagement with local government stakeholders. Building supportive relationships with these entities is important to ensure the continuity and success of the program.

8.2 Key factors

This section summarizes our concerns (or lack thereof) about different aspects of a new charity putting this idea into practice.

Table 7: Implementation concerns

| Factor | How concerning is this? |

| Talent | Low Concern |

| Access to information | Low Concern |

| Access to relevant stakeholders | Moderate Concern |

| Feedback loops | Moderate Concern |

| Funding | Moderate Concern |

| Scale of the problem | Low Concern |

| Neglectedness | Low Concern |

| Execution difficulty/Tractability | Moderate-high Concern |

| Negative externalities | Low |

| Positive externalities | High |

Talent

We think that there are not any very specific skills that a founder needs to start this charity. The typical ambitious and entrepreneurial generalist who goes through the CE incubation program should be able to start this charity successfully.

Table 8 provides some nice-to-have qualities, but by no means are they required traits. Often if one of the co-founder pair has the trait, it would offset another cofounder lacking in that trait.

For example, although male founders can definitely find success in starting this charity, we think it would be beneficial for one of the co-founders to be a woman. This may add a minor amount of trust and credibility and make it slightly easier to fundraise, for example. However, we expect a male founder with good fundraising skills to offset such differences.

Table 8: Founder requirements and nice to haves

Must have

| Preferable (offsets a 10% diff in incubatee strength) | Preferable, all else equal |

Experience operating in rural areas in sub-Saharan Africa or running community-based interventions.

Experience training health workers or running training programs for health workers | Global health and development background

Maternal and neonatal health background

Women

From LMIC background |

Access

Information

Access to information is not a huge concern, as the non-profit would be able to receive technical support from WCF.

Relevant stakeholders

We have some concerns about finding lay workers to facilitate the groups. It is highly preferable that they are local women who are literate. It’s unclear if they would be willing to do the job.

We are confident that WCF would be willing to support the non-profit.

We have some uncertainties about whether the charity could secure partnerships with local health facilities, which would significantly improve measurement and evaluation.

Feedback loops

We are moderately concerned about the feedback loops for the intervention. The intervention requires a substantial amount of surveying and monitoring of the quality of PLA groups, as well as maternal mortality. We do not think this is impossible, but given the number of groups that are required at scale, this would not be very easy.

The longer-term metrics and endline results (maternal and neonatal mortality) are not a huge concern. As illustrated in Figure 9, the researchers from the studies randomly sampled and surveyed a proportion of the larger community (not just group members). They tracked the metrics of interests, such as pregnancies, births, and deaths, as well as behavioral changes throughout the intervention. Beliefs and attitudes can be measured via qualitative surveys.

We are more concerned about shorter-term metrics that allow a charity to gauge the implementation quality of groups. Each facilitator should report back on each group's progress, including what was discussed and what solutions were implemented. In addition, they can receive feedback from group members through informal conversations. As with the scaled-up intervention in India, facilitators can observe other group meetings and provide feedback for other facilitators.

If the charity could partner with local health systems, they could potentially receive additional data about health facility attendance rates and mortality rates of all pregnancies.

Apart from this, recruitment metrics are not concerning as the facilitator would be able to track the number of participants in each session and their names. WCF mentioned that even the people who show up once have an impact on outcomes.

Funding

Funding from funders in the CE network

GiveWell is interested in funding work in this space, provided the non-profit can run PLA groups at a sufficiently low cost. They have recently given a scoping grant to Spark Microgrant to assess the costs and feasibility of a pilot.

Maternal, Neonatal, and Reproductive Health charities have consistently received above-average seed grants within our seed network. In the latest rounds, Maternal Health Initiative and Lafiya Nigeria have received the most funding in their respective rounds. However, this may reflect their appetite for family planning charities more than MNH charities.

Broader funding sources

There is a growing pool of funding dedicated to MNH. According to the VizHub Development Assistance for Health Trends. From 2010 and 2019:

- Newborn and child health was the third biggest grower with an ~85% increase (note that the largest, by a wide margin, was communicable diseases - COVID).

- Reproductive and maternal health grew by ~17%

- This is driven by increased funding from development aid from most countries and large foundations, such as the Gates Foundation.

However, a lot of this funding goes towards large players like Jhpiego.

Experts have also cautioned that funders are less likely to fund Western founders and non-female teams. The Gates Foundation has funded pilots in Ethiopia (from the conversation with WCF), suggesting that they are open to funding this intervention.

WCF has also noted that funding is a concern as governments have a limited appetite to fund multiple community-based programs. However, it is helpful that PLA is the only “community mobilization approach available for maternal and newborn health” that the WHO recommends (WCF).

Scale of the problem

Maternal and Neonatal Health is a large, albeit decreasing, burden. In 2020, out of the 135 million births worldwide, there were approximately 1.4 million stillbirths and 2.4 million neonatal deaths (OWID, Boerma et al., 2023). Maternal mortality is also high, with an estimated 300,000 women dying during pregnancy (Boerma et al., 2023). Over 90% of these deaths occur in LMICs.

We think it is also interesting that this intervention targets a more rural demographic, which has a higher burden and differs from typical urban-focused interventions.

Neglectedness

We think that PLA is a neglected intervention within MNH. While the broader cause area of MNH is becoming less neglected, evidenced by the increased flow of funds into the space, few organizations, especially international NGOs, dedicate resources to this intervention.

Experts and funders have commented on the difficulty of finding implementation partners to do the work. The biggest actor in space, WCF, is only scaling to 3 additional countries in the next year.

Tractability

Tractability is our main concern. It seems there is a large amount of variability in the intervention, based largely on the participation rates of pregnant women within a catchment area. We have outstanding uncertainties regarding whether a charity can effectively target and recruit pregnant women in groups.

We think recruitment is more important than targeting. As mentioned, capturing a large percentage of community pregnancies is more crucial than increasing the percentage of pregnant women within the group. Hence, we think recruitment is more important than targeting, as the group can be larger in size and have lower percentages of pregnant women without compromising effectiveness.

We emphasize this point because we think recruiting is easier than targeting by generating enthusiasm and buzz within the community to join the groups, rather than being selective with whom to promote to (See Annex for a description of what recruitment activities look like).

Experts and studies have mentioned that it is important for the facilitators to be trusted by the community. CHWs may have limited capacity, which may be an impediment to scaling the intervention. However, trained local women seem to facilitate the groups just as effectively.

There are some concerns regarding maintaining the quality and fidelity of implementation. When the charity operates at scale, it oversees thousands of women's groups. We only have one example of this intervention scaled up to cover a million+ births (Nair et al., 2021). However, the number of births we expect to reach in our modeled CEA covers a smaller number of births, in a similar range to the number of births covered in the studies.

We have minor concerns about training the facilitators, but WCF has said that they would be happy to use their expertise to help us. Their technical assistance package for organizations predominantly includes training. We have written more on what the training looks like in the Annex.

Externalities

This intervention presents both potential positive and negative externalities.

While the impact on child mortality is not fully established, several studies suggest a possible positive effect. Additionally, there is evidence indicating increased contraceptive use, which could prevent unintended pregnancies. However, the CEA did not include these effects.

Most studies also report an enhanced sense of female empowerment among participants, a benefit that is challenging to quantify and thus not incorporated into our modeling.

Furthermore, PLA may contribute to reducing inequality. For instance, a meta-analysis of four PLA studies found that PLA can lead to equitable reductions in neonatal mortality across various socio-economic groups (Houweling et al., 2016).

PLA groups also have the potential to be adapted to assist women in addressing other aspects of their lives, including economic issues or gendered violence.

On the other hand, PLA requires substantial time commitment from mothers and, if done poorly, could potentially reinforce harmful behaviors. The time that women take to meet could otherwise be spent productively. It is also important to consider that poor implementation might inadvertently produce negative externalities and reinforce harmful health behaviors; however, the robust effect sizes observed in studies mitigate this concern.

Remaining uncertainties

We have remaining uncertainties about the idea.

- Can the charity find trusted facilitators? We suspect this varies by geography.