Debate: Depopulation Matters

By Richard Y Chappell🔸 @ 2025-07-01T12:40 (+57)

After the Spike: Population, Progress, and the Case for People by Dean Spears and Michael Geruso is one of the most bracing, insightful, and important books I’ve ever read. I strongly recommend that everyone reading this sentence go and pre-order it immediately. (That’s the first time I’ve ever issued such a universal recommendation, so it isn’t cheap praise.) In my two-part review, I’ll try to convey some of why I think so highly of the book. The game plan:

- Part #1 (today’s post) explores why depopulation is bad. A vital corrective to all those still stuck in the 1970s “population bomb” mindset of thinking that we have “too many people on the planet already” and welcome having fewer people in future.

- Part #2 surveys what doesn’t work—from far-right reproductive illiberalism (which is outright counterproductive), to moderate-left proposals to financially support families (which help a bit, but still don’t suffice)—before turning to the trickier question of what to try next.

The Facts

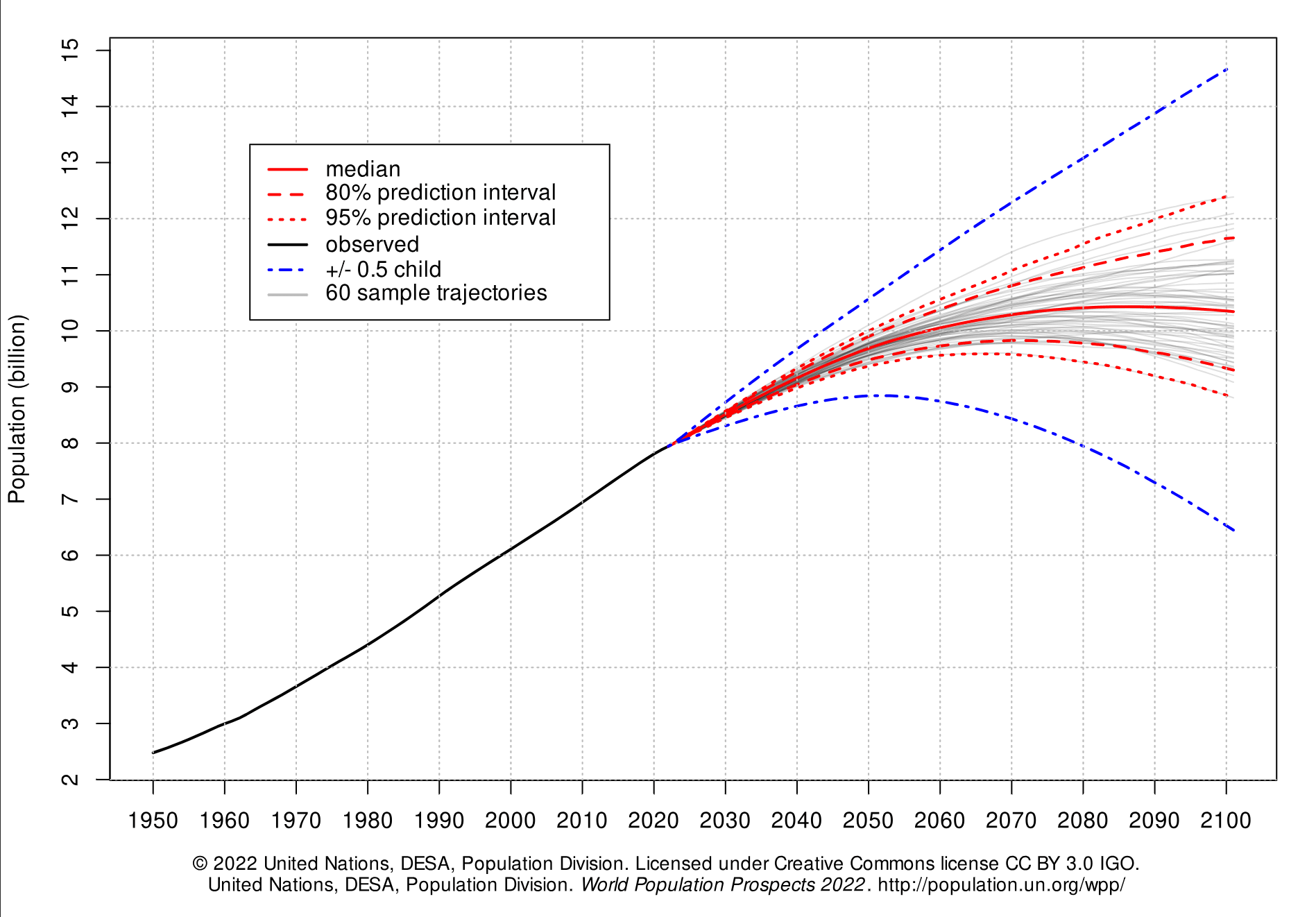

Earth passed “peak baby” in 2012. Now fewer babies are born each year. Demographers expect peak population to be reached in a few decades, followed by a shocking plummet.[1] Below-replacement fertility is perhaps the simplest and most probable extinction risk around:

If humanity stays the course it is on now, then humanity’s story would be mostly written. About four-fifths written, in fact. Why four-fifths? Today, 120 billion births have already happened,[2] counting back to the beginning of humanity as a species, and including the births of the 8 billion people alive today. If we follow the path of the Spike, then fewer than 150 billion births would ever happen. That is because each future generation would become smaller than the last until our numbers get very small.

Something needs to change, and drastically, if humanity is to avoid this fate. (As Spears and Geruso note: “in none of the twenty-six countries where life-long birth rates have fallen below 1.9 has there ever been a return above replacement.”)

Is Population Bad?

I’ve noticed that many—esp. older—academics seem stuck in the mindset of worrying about “overpopulation”, and hence welcome the prospect of depopulation. The crux of the disagreement may come down to a pair of empirical and ethical disputes:

- On present margins, do people on average have more positive or negative externalities? (Empirical question about causal-instrumental effects)

- Do human lives, on average, have intrinsic value? (Ethical question)

The bulk of the book is dedicated to answering the empirical question, and allaying the concerns that lead too many to curse humanity and wish for fewer of us. I won’t be able to do their comprehensive discussion justice here, but just to flag a few highlights:

Climate change

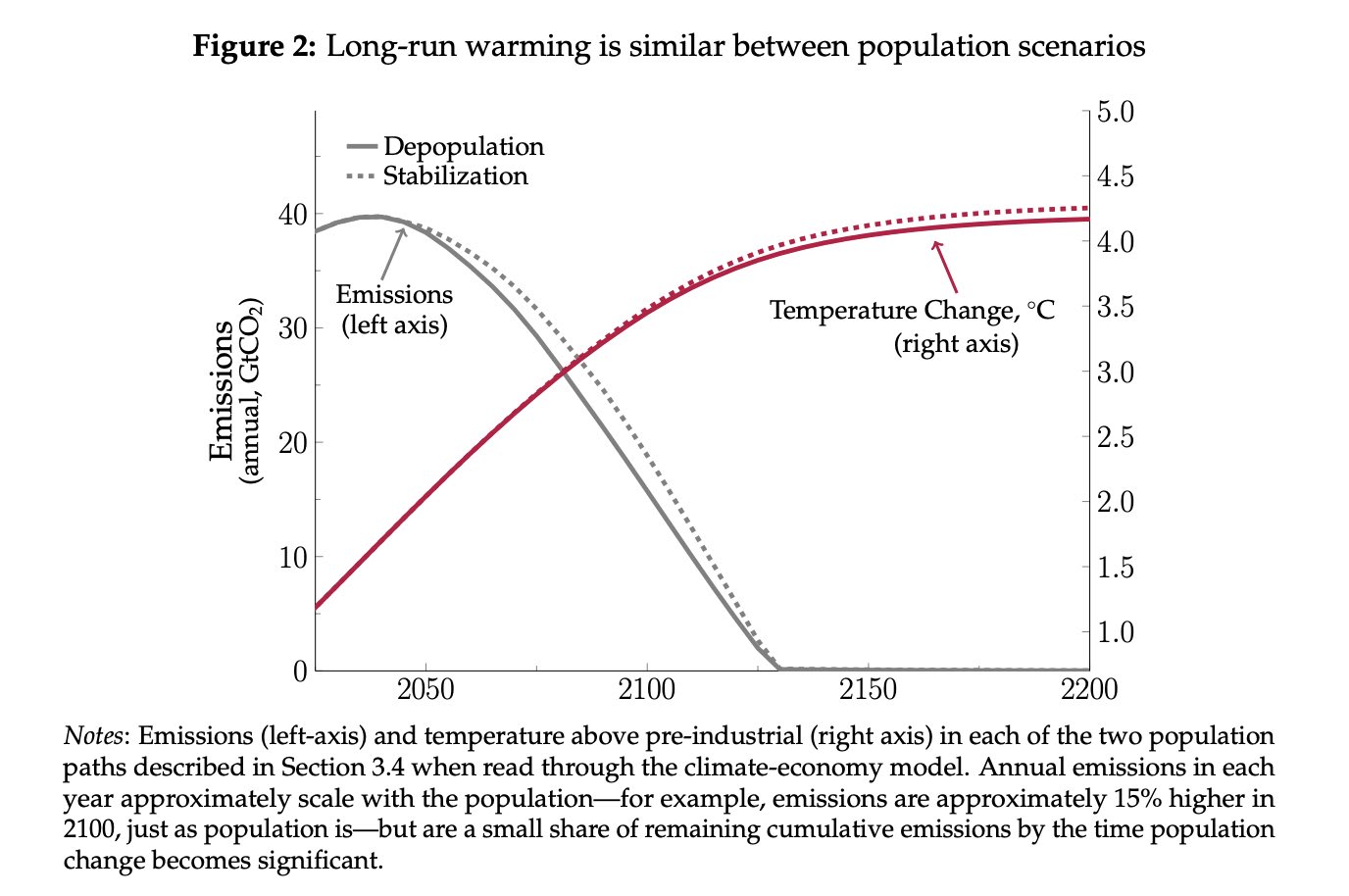

The most commonly-expressed concern is, of course, climate change. And here, Spears and Geruso have an absolutely decisive response: timing is everything, and depopulation is too slow to help. We need to decarbonize over the coming couple of decades. Depopulation after 2080 (or whatever) won’t help with that. If anything, it may just make things worse (as society shifts more and more of its limited resources towards sustaining its disproportionately elderly populations, leaving less for investments in green research and infrastructural deployment to actually solve the problems that past generations created). As Spears & Geruso put it:

The only way to confront climate change is to reach net-zero emissions—and soon. If we do that, we will have averted the worst disaster. And if we do that, then an additional person, or an additional billion, born afterward doesn’t matter for emissions. At all. Zero times 9 billion is the same number as zero times 8 billion. Climate progress may turn better or worse in the coming decades. But that will be determined by technology, social awareness, and policy, not by population size.

Perhaps the biggest mental shift needed here is to stop thinking of passivity as the solution (“if only there were fewer people consuming energy!”), and instead recognize that we need active solutions—green innovation and deployment—so that future generations are helping rather than harming the environment. Reducing birth rates now doesn’t reduce emissions in the next 25 years, but it does mean fewer scientists developing breakthroughs in 2050, and less economic capacity to implement new solutions at that time.

Progress comes from people

Chapter 6, “Progress comes from people”, may be my favorite. It explains the following key insights from the science and economics of innovation (why we should have a fundamentally “positive-sum” rather than “zero-sum” view of other people):

Populous is prosperous. A more populous future would raise living standards. Mainly this is because people contribute to the ideas, creativity, experimentation, and technology that benefit others.

They illustrate this with the example of “Kangaroo Mother Care” (KMC) saving the lives of low-birthweight babies in India today, after being invented in Colombia in 1978 and then tweaked and refined by many in the years since.

Spears & Geruso add: “Somehow we’ve made everything more abundant as the population has soared. Is that history a fluke?… It’s time to understand the how and why so we can see what we might lose as humanity’s numbers recede.”

A prize-winning idea: More of us generate more ideas. And that can mean better lives for each of us.

A fact about facts: Facts don’t get used up, but they might go undiscovered.

Strength is in our numbers, not just our rare luminaries. Non-rival innovation is so powerful that even without outliers—even in an alternative universe in which everyone was equally (unexceptionally) intelligent, adventurous, creative, kind, and organized—progress would depend on population size.

Plus a key idea from chapter 7:

How not to get a slice of pie. Having fewer people around would mean there were fewer people who want exactly what you want. And that might be a problem for you getting what you want. Your neighbors are not eating your pie slice. They’re the reason someone is baking.

They conclude:

Whatever it is you value that humans make and do, was there less of it a century ago, when there were fewer of us on the planet together? Vaccines? Streaming, high-budget television? Books or newsletters by a writer who is just your style? Social statistics and ideas about how to use them to build better communities? If so, the Spike warns you not to be confident that a few hundred million people will pull it off in a small and shrinking future. Nobody knows what a complex, interdependent modern economy would be able to produce when there are so few people to fill its niches. The appearance of niche economic specialization in human society is so new, on the scale of the Spike, that nobody should pretend to know what would happen without it.

(Maybe AI could fill the void, but we surely don’t want to gamble the future of civilization on that.)

More Good is Better

Chapter 8 turns to a moral principle that's dear to my heart:

More Good is Better. It’s better if there is more good in the world, other things being equal, and worse if there is less. That includes good lives: It’s better if there are more good lives.

Like beneficentrism, I don’t think this should be at all controversial. Whatever deontic constraints, prerogatives, and partialities you’re inclined to accept, you should also accept that More Good is Better (all else equal).

Spears & Geruso offer a powerful thought experiment to those who claim that there was no “shortage” of people when global population was just half what it is now: Imagine that half the people you know and love never existed. You wouldn’t miss them in particular; you wouldn’t know what you’re missing. But still, comparing our world to that imagined half-world, we are surely right to be glad that those extra good lives exist. (You would seem not to fully cherish them if you didn’t feel this way, and didn’t regard the preference as one that is warranted by the intrinsic value of your loved ones. Really, anyone who fully knew them ought to wish them well and be glad that they exist.)

Now generalize. Just like it isn’t only bad when you or your loved ones suffer (others’ suffering matters too), so it isn’t only good when you or your loved ones exist (others’ existence matters too). There is no good reason to deny this.[3]

Related Reading

While you wait for the book’s July 8 release date, I recommend also checking out:

- Victor Kumar on The Vanishing of Youth

- Alice Evans and Ross Douthat on the collapse of coupling as a possible (partial) explanation of fertility decline. (Go fall in love, people!)

- Noah Smith on ‘The dawn of the posthuman age’—on the trends of fewer families and ever-increasing time spent online.

Framing the Debate

Just a reminder that I particular welcome debate around the two key questions:

- Do people, on average, have positive or negative externalities (instrumental value)?

- Do people's lives, on average, have positive intrinsic value (of a sort that warrants promotion, all else equal)?

Two common pitfalls of low-quality public debate on this topic that I'd rather avoid:

- As per footnote 3, please don't conflate pro-natalism with procreative duties or opposition to reproductive freedom. (If you want to raise concerns in that vein, make sure you first read my post on the “No Duty → No Good” fallacy.) Part 2 of my review will share more from the book on why coercion is not the solution.

- Please don't conflate concern about global population decline with far-right obsessions about race, "great replacement", etc. I'm all for more immigration (I'm an immigrant myself), but moving people around does not address global depopulation. Its virtues lie elsewhere (increasing freedom and labor productivity, reducing poverty, etc.).

- ^

The precise gradients will vary depending on whether global average fertility rates are closer to 1.8 or 1.2, but the general shape of the exponential curve is surprisingly similar either way.

- ^

Though I’m skeptical that “# of births” is the right metric for partitioning the human story. Since infant mortality used to be vastly higher (and life expectancy in general much lower), we presumably have a higher proportion of life-years still to go than this passage might suggest. So the remaining births to come might yet contribute a disproportionately large amount to humanity’s story. It’s complicated :-)

- ^

Some bad reasoners, frightened by the false specter of procreative duties, commit the “No Duty → No Good” fallacy. So I was happy to see Dean & Mike run with my suggested kidney donation analogy to push back against this!

Larks @ 2025-07-03T02:57 (+24)

Some people believe that, while depopulation is bad, we're not at crunch time yet, so we can reverse it later. I worry that this under-estimates the extent of positive feedback loops. It seems to me that, as birth rates have fallen, policy and culture have become less supportive of parenting, which in turn makes parenthood less attractive. I worry that voters are not forward looking enough to recognize that, even though they may not have children at the moment, it is nonetheless good for the future for parenthood to be supported.

Some examples of anti-parenthood policies and cultural memes:

- Large transfers from young to old (e.g. unfunded state pensions).

- NIMBYism increasing the cost of additional bedrooms.

- Couples are the decision maker for reproductive choice, bear most of the costs of having children (both financial and opportunity cost) but few of the benefits (most go to the child or to the taxpayer).

- High prestige given to education and career success, low or negative given to parenthood.

- High risk aversion about children (CPS, car seats, stranger danger, etc.)

- Age stratification, media representation and fewer cousins reducing social salience of babies for young couples.

- Sex education and family planning focused on avoiding pregnancy, not on actually having families.

- Exclusion of families from recreational activities.

- Lack of support for young parents in education.

In general I expect falling birth rates to make most of these factors worse through de-normalisation of parenthood and reducing the young parent influence base, further reducing birth rates, absent some major change.

Alfredo Parra 🔸 @ 2025-07-02T06:28 (+24)

Depopulation is Bad

I remain unconviced by the arguments in the book (based on this post). My main disagreement is that it assumes that the main downside of a larger population is climate change (which I don't think it is), and then goes on to focus exclusively on all the great things we could have with more people. Perhaps not surprisingly, I think this debate is not complete without bringing up the problem of extreme suffering:

More Good is Better. It’s better if there is more good in the world, other things being equal, and worse if there is less. That includes good lives: It’s better if there are more good lives.

The above begs the question. Sure, more good is better, but the book title is not "the case for happy people." Doubling the population would mean:

- 560 million people living with depression instead of 280 million.

- 1.4 million people committing suicide every year instead of 700k.

- Doubling the number of people being tortured in prison camps, living in totalitarian regimes, living in war zones, living with cluster headaches, etc.

- Doubling the consumption of chicken, fish, etc.

Maybe one could argue that growing the population would also help us fix all of the above faster, but I seriously doubt it (and it would seem to me more like an instance of suspicious convergence).

The book authors seem to be basically saying "wouldn't it be awesome to have more people like us? Healthy, wealthy, happy-go-lucky, living in a free democracy, and with such high IQ that we might invent a new vaccine?" (Sorry, this might be unfair, but that's at least the vibe I get from this post.) But I think we absolutely need to think about those living in agony too. Until then, I'm unconvinced.

Maybe less importantly (because it may be rather a matter of aesthetics), I'm also not moved much by the argument "aren't you glad to have more books, magazines, high-speed streaming, etc., and wouldn't it be great to have more of that?" There's something hungry ghost-y about it that goes against my striving to be content with less. Like, yes, I admit I really like vaccines, but maybe our goal should be "let's shift our societal priorities such that fewer people go on to become TV producers and instead become vaccine researchers."

Something similar applies to this:

Imagine that half the people you know and love never existed.

I think the thought experiment is trying to evoke a feeling of sadness at the thought of never having met half the people in your life, but to me it also implies that, right now, I should be sad that I don't have twice the friends I have. I reject this implication.

Anyway, I still appreciate the book summary and will be thinking about the topic more as a result. And I'm still open to changing my mind if there are other arguments related to the problem of extreme suffering.

Jack_S @ 2025-07-02T14:52 (+17)

I'm very torn on this question, so let's shoot for 60%.

Many people are probably thinking about the impact on animals, which most EA forum readers will probably agree is a far stronger argument for anti-natalism than climate.

There's a set of arguments, recently articulated by Bentham's Bulldog, which looks like this:

- High birth rates are good because human lives tend to be good

- But humans kill animals for food and incentivise factory farming, which clearly overwhelms the positives of a human life, therefore high human birth rates might be bad (meat-eater problem)

- But humans also incidentally prevent the lives of billions of insects and fish, and insect lives are net-negative, therefore this clearly overwhelms both farmed animals and the value of a human life, therefore high birth rates are actually good!

- And more humans are likely to make the far future even better for animals, so high birth rates are even more good!

Of course we should take this argument seriously, but:

1) Having children seems an incredibly inefficient way of maximising your destruction of insects! If insect suffering does overwhelm other effects, this fails to provide an effective utilitarian argument for human pronatalism.

2) Based on current human values and preference for environmental protection/rewilding, it seems plausible to me that the marginal human may not decrease wild insect numbers. Similarly, I can see a far-future where more humans make the world worse for both farmed and wild animals.

3) Practically, I suspect you'll lose most ethically minded individuals, or people who have very low estimates of insect/fish consciousness, at step 2 - the meat-eater problem. Step 3 requires taking quite a bitter pill in terms of cross-species anti-natalism and the disvalue of existence more generally. "Open Phil-brand EA", which generally disregards insect and wild animal welfare, would also have to reject step 3, and may therefore have to conclude that anti-natalism is good.

4) More personally, it does seem a bit weird feeling that my wonderful little baby's main source of value in the world is his insect-destroying potential.

Ian Turner @ 2025-07-01T13:27 (+13)

Not addressed by this article is that growing the human population isn't that expensive, if you target your intervention. Like, we could probably incentivize births in (for example) Uzbekistan for a tiny fraction of the cost of doing so in (for example) South Korea.

Jack_S @ 2025-07-01T14:27 (+5)

Maybe you read it, maybe just a coincidence, but I wrote a blogpost that (using a toy model) found Uzbekistan to be the most promising country for incentivising birth rates!

Ian Turner @ 2025-07-01T14:43 (+2)

Not a coincidence! I remembered reading this but couldn't find the link.

vandermude @ 2025-07-03T00:03 (+12)

Overpopulation is one of the driving forces of the climate crisis. We relieve the pressure on the environment with less people. If there are too many old people because of it, they can work longer, there can be more resources spent on them, or there can be more automation. We are on the way to defusing the population bomb. Why stop now?

Yes, I am one of those fuddy-duddies in my 70s who went to college in the hippie era. And I never really bought into the Population Bomb hype, to be honest. I am also a big fan of Julian Simon ever since the early 1990s. This "depopulation is bad" argument smacks of "quantity over quality" to me. I agree with Simon about "The UItimate Resource". But we don't really need to keep growing to achieve it. We need to get the best quality of life for everyone, regardless of the total population. I just happen to think that stopping population growth is not bad in and of itself.

Richard Y Chappell🔸 @ 2025-07-03T00:17 (+5)

Just to clarify: Spears & Geruso's argument is that average (and not just total) quality of life will be significantly worse under depopulation relative to stabilization. (See especially the "progress comes from people" section of my review.)

David Mathers🔸 @ 2025-07-01T16:07 (+11)

"Below-replacement fertility is perhaps the simplest and most probable extinction risk around"

For it to present a significant extinction risk, you'd need current demographic trends to persist way past the point where changes in population have completely transformed society to the point where there's no reason to think current demographic trends will hold.

Derek Shiller @ 2025-07-01T20:43 (+4)

I would think the trend would also need to be evenly distributed. If some groups have higher-than-replacement birth rates, they will simply come to dominate over time.

Richard Y Chappell🔸 @ 2025-07-01T21:55 (+3)

The authors discuss this a bit. They note that even "higher fertility" subcultures are trending down over time, so it's not sufficiently clear that anyone is going to remain "above replacement" in the long run. That said, this does seem the weakest point for thinking it an outright extinction risk. (Though especially if the only sufficiently high-fertility subcultures are relatively illiberal and anti-scientific ones - Amish, etc. - the loss of all other cultures could still count as a significant loss of humanity's long-term potential! I hope it's OK to note this; I know the mods are wary that discussion in this vicinity can often get messy.)

Richard Y Chappell🔸 @ 2025-07-01T16:13 (+3)

What reason is there to think that demographic trends will suddenly reverse? If it isn't guaranteed to reverse, then it is an extinction risk.

David Mathers🔸 @ 2025-07-01T16:22 (+6)

The risk is non-zero, but you made a stronger claim that it was "the most probable extinction risk around".

EDIT: As for reasons to think they will reverse, they seem to be a product of liberal modernity, but currently we need a population way, way above the minimum viable number to keep long term modernity going. Maybe AI could change that I guess, but it's very hard to make predictions about the demographic trend if AI does all work.

Richard Y Chappell🔸 @ 2025-07-01T16:41 (+5)

I wrote "perhaps the simplest and most probable extinction risk". There's room for others to judge another more probable. But it's perfectly reasonable to take as most probable the only one that is currently on track to cause extinction. (It's hard to make confident predictions about any extinction risks.) I think it would be silly to dismiss this simply due to uncertainty about future trends.

Ian Turner @ 2025-07-01T13:24 (+11)

I think those in favor of higher population should say what they think the ideal human population should be. Most of the hand wringing about population seems to be about whether it should be higher or lower than it is now, but that question seems to be anchored by the current population? If indeed "More Good is Better", does that imply that an Earth with a trillion people would be better than our Earth today? Because personally, I don't really agree with that.

Richard Y Chappell🔸 @ 2025-07-01T14:53 (+9)

As a general rule, it isn't necessary to agree on the ideal target in order to agree directionally about what to do on present margins. For example, we can agree that it would be good to encourage more effective giving in the population, without committing to the view (that many people would "personally disagree" with) that everyone ought to give to the point of marginal utility, where they are just as desperate for their marginal dollar as their potential beneficiaries are.

The key claim of After the Spike is that we should want to avoid massive depopulation. Whether you'd ideally prefer stabilization, gradual population growth, or growth as fast as we can sustainably maintain without creating worse problems, isn't something that needs to be adjudicated -- and in fact seems a distraction from the more universally agreeable verdict that massive depopulation is bad and worth avoiding.

Zlatko Jovičić @ 2025-07-01T14:45 (+5)

In my opinion the trajectory of population might be more important than the sheer number you end up with.

Ideal trajectory is that of slow/moderate growth as long as the planets we occupy (Earth and whatever other planet we occupy in the future) can support increasing number of people without significantly compromising living standards and exhausting resources.

After that point population should stabilize. Neither grow nor shrink but stay constant.

Ideally population should stop growing at around 80% of the carrying capacity of the planets we occupy, as approaching 100% would be too risky.

Now population decline is typically a bad trajectory for 2 reasons:

- It is a symptom of some problems in society (unless intentional)

- Over the long term it leads to extinction

For this reason, I think population decline can only be good as a short term intentional / consensual process in overcrowded worlds.

If we're already overcrowded (which I doubt), in that case it wouldn't be too bad if population falls a bit, but it must be a short term and reversible decline.

And we're witnessing some concerning trends, like TFR staying well below replacement for long term and failing to recover in most of the developed nations. And the developing nations are also on the same track, just lagging a couple of decades.

Even if population decline improves sustainability, that would be a good consequence, but the process itself might still be bad, because it's not result of intentional decision, but of increasing number of people failing to reproduce in sufficient number due to various limitations of our society. So population decline, even if it improves sustainability (which would be a beneficial side effect), would still reveal some structural problems of our current society and economic system, and these problems would likely still need some fixing even if we decide it's OK for population to fall a bit for a short while.

The point is that we should be able to reproduce in sufficient number if we want to. It seems that right now we aren't even able to do it. Most of the people end up with smaller number of kids than what they wanted.

NickLaing @ 2025-07-01T18:02 (+9)

If anyone wants an 8 minute podcast version, they do a pretty good job here!

https://www.npr.org/2025/07/01/1255040246/why-economists-say-we-should-have-more-babies

Ariel Simnegar 🔸 @ 2025-07-01T22:09 (+8)

Depopulation is Bad

Assuming utilitarian-ish ethics and that the average person lives a good life, this follows.

The question gets much more uncertain once you account for wild animal effects, but it seems likely to me that the average wild animal lives a bad life, and human activity reduces wild animal populations, which supports the same conclusion.

Joel Tan🔸 @ 2025-07-01T16:20 (+8)

I think the most plausible meta-ethical view grounds objective moral value in preferences (which presuppose people/sentient creatures with preferences), so there's no non-circular way of solving the non-identity problem (and I would bite the bullet). The corollary is that mere addition isn't atemporally good.

In other words, the benefits/costs of depopulation is entirely in the impact of the people who would exist anyway, and there's a pretty clear economic case (e.g. need to maintain a stable working age to dependent ratio, and to avoid vicious cycles relating to escalating pension costs and gerontocracy)

ben.smith @ 2025-07-03T04:46 (+7)

Depopulation is Bad

When I pit depopulation against causes that capture the popular imagination and that take up the most time in contemporary political discourse, I think depopulation scores pretty high as a cause and I am glad it is getting more attention.

When I pit it against causes that the EA movement spends the most time on, including AI x-risk, farmed animal welfare, perhaps even wild animal welfare, and global poverty, I find it hard to justify giving it my considered attention because of the outsized importance of the other problems.

AI x-risk is important because the long term future could be at stake in the next few years or decades. The other two causes are important because billions of people and trillions of animals are experiencing needless suffering now. It's hard to see depopulation holding a candle to those cause areas.

I would like to see more mainstream funding and attention given to working on depopulation. On the other hand, unless I'm missing something, I would not like to see any funding or human capital diverted from ai x-risk, animal welfare, and global poverty.

Catherine Low🔸 @ 2025-07-03T00:50 (+7)

Depopulation is Bad

I think humans are good. And larger groups of people can do a lot more (more innovation, more cultural activities, more variety of human experiences).

Right now, in 2025, I would not advocate for more people due to animal welfare and environmental costs of having more people.

But looking at the many countries that have gone through a very demographic transition to less-than-replacement fertility (and all the other countries that seem to be following a very similar trajectory), I'm worried that the population will plummet shortly after it hits peak.

I'm not sure what to do about it. And I'm worried about governments/other people in influence increasingly trying to increase fertility in ways that reduce individual freedom.

Henry Howard🔸 @ 2025-07-02T00:24 (+7)

Depopulation is Bad

When parents have fewer children it means their attention and resources are stretched across fewer kids. I think this is, on average, gives these kids better opportunities.

Also generationally, wealth will accumulate among a few descendants rather than being diluted.

I think the concerns about lower workforce aren't a big deal because of increased mechanisation and the huge numbers of people in the world that don't currently have the opportunities to work productively.

I think the concerns about fewer people meaning less innovation/lower chance of geniuses emerging neglects that currently 90% of the world is locked out of these opportunities anyway because of poverty.

Kevin Kuruc @ 2025-07-01T17:35 (+7)

Depopulation is Bad

I think this is directionally likely to be true, and I agree with the main claims of the book that Richard nicely summarizes here. That shouldn't be too surprising -- I work with Mike and Dean and helped with a bunch of the research! Thanks for sparking this debate :)

My main uncertainty has to do with a further idea I've been developing (with Loren Fryxell). The thrust of it can be seen with an oversimplified example. Suppose it will take 200 billion human-lives worth of progress to get to the technology that is so dangerous that we go extinct soon after its invention. The effect of adding people today is to accelerate the arrival of this dangerous tech in a way that undoes all of the purported benefits of the earlier people (ie, the exact same number of lives with the exact same average quality are lived). The model we write down is in agreement with essentially all of the important claims in the book, it just layers on an explicit extinction assumption that turns out to generate a negative effect that exactly offsets the positive ones.

This toy example isn't enough to move me to be completely uncertain about whether depopulation is bad (I put 60% agreement, after all). But we show that additional people in the near-term can be harmful, neutral, or beneficial depending on assumptions made about the shape of the people-progress relationship and the types of existential risks we face. I am not very confident that our world is one where those parameters are such that people today are beneficial--there's too little evidence imo.

Zlatko Jovičić @ 2025-07-01T22:55 (+7)

This reminds me of doomsday argument, and even more of "black balls" from Bostrom's Vulnerable World Hypothesis.

But I find some issues with it:

First of all there's no guarantee that there is such a technology that inevitably leads to extinction.

Second, even if there is such a technology, there's no guarantee that we will ever develop it, regardless of how many people are born in the future. (We might use proper safety measures and avoid it forever, or until we go extinct from some other cause)

Third, even if we do develop it eventually, the speed of its arrival probably depends on many of factors of which the total number of human lives probably isn't most important. (As more important factors I'd mention, presence/absence of AGI/ASI and whether they are aligned, whether we are pursuing differential technological development or not, how robust our institutions are at preventing existential risks, how good is global coordination and cooperation, how closely the development of potentially harmful technologies is monitored, etc.)

Fourth, even if such a deterministic relationship does exist, and 200 billion human lives inevitably leads to development of such a technology, from utilitarian point of view it doesn't seem to matter much when we'll reach 200 billion humans who have ever lived, as whenever we reach it, the total amount of humans who have ever lived will be the same.

Lorenzo Buonanno🔸 @ 2025-07-02T18:04 (+6)

Depopulation is Bad

Even the most pessimistic estimates expect the global population to actually start declining only in ~2050 and to reach the 1960 population levels well after 2100.

If this actually becomes an issue by 2100, I'm optimistic it will be relatively tractable by then

Tobias Häberli @ 2025-07-02T18:56 (+2)

Interesting that 80% disagree can mean "depopulation is pretty likely good" (e.g. this seems to be Alfredo Parra's view) or "depopulation likely hardly matters" (which I think is your view).

Toby Tremlett🔹 @ 2025-07-02T13:54 (+6)

Depopulation is Bad

I'm really not sure. I want the population of our (hopefully) long future to be large and full of flourishing, but I don't know if or how a projected population decline over the next century is likely to affect that. My guess would be that we are fairly comprehensively uncertain at this point. So my current reaction is, I'll pay some attention but I'm not currently concerned.

Plasma Ballin' @ 2025-07-01T15:26 (+6)

Depopulation is Bad

I don't know of any plausible axiological theory on which this is false. On the total view, an increased population is good as long as each person's life is good, and they aren’t such a burden on everyone else so as to drag down the overall welfare. That seems quite obviously true in the modern world. On the average view, depopulation is bad as long as it lowers average welfare, which it almost certainly will due to the inability to run institutions built in the higher-population age, the loss of economies of scale, etc. Even on a person-affecting view, depopulation is bad - it doesn't just negatively affect people who never come to exist as a result, but also the people who do exist.

Toby Tremlett🔹 @ 2025-07-01T13:34 (+6)

Discussion of this topic can be heated or emotionally difficult for some. We would like to remind everyone to adhere to forum norms: be respectful, interpret others' comments charitably, and avoid personal attacks. Please don’t assume other people’s values or backgrounds.

As Richard notes at the end of the post, reproductive rights are an orthogonal conversation — you can be worried about low fertility rates and population decline without it affecting your view on abortion, contraception, or social conservatism.

However, some readers may come from contexts where severe restrictions have been placed on their ability to make personal decisions — for example, related to family formation, reproduction, or identity — under the justification of managing population trends. This means that this isn’t a purely theoretical debate for everyone.

We ask that posts avoid inflammatory claims, particularly those that touch on gender, race, ethnicity, or geography in ways that could be harmful or exclusionary. Moderators will be closely monitoring this thread for norm-breaking comments.

Personally, I’d be most interested in a conversation focused on Richard’s argument — i.e. the case for and against a lower population being a bad thing.

P.S. – The best-case scenario (and the most likely one, based on my understanding of the Forum community) is that this comment ends up looking pretty unnecessary/ overkill.

P.P.S – I like Kelsey Piper’s piece can we actually be normal about birth rates?, which highlights a few ways this conversation can get weird/ hateful/ impractical, in ways it really doesn’t need to.

Larks @ 2025-07-01T18:34 (+16)

This means that this isn’t a purely theoretical debate for everyone.

Most forum readers are continually surrounded by factory farmed meat. Some will live in areas with Malaria or other problems associated with global poverty, some will experience the debilitating pain of severe headaches and other conditions. All readers live in a world facing the risks of nuclear war, global pandemics, and the rise of unaligned artificial intelligence. Most debates we have here are not purely theoretical for everyone! That doesn't mean we can't approach them logically.

Toby Tremlett🔹 @ 2025-07-02T08:17 (+2)

You're right! Maybe it's a bit of a lazy phrase. Another way of phrasing it is that this debate can very quickly become very personal, in ways the other debates you list in practice do not. From my read of the comments, it hasn't so far, so I'm hopeful (as I mention in P.S.) that this mod comment is an overreaction.

Jason @ 2025-07-01T13:52 (+4)

[vote comment, very shallow take waiting for train] Moderate depopulation isn't bad, at least not right now. The limiting factor on climate change is more likely political will / willingness to make financial sacrifices, not a lack of people in 25-30 years to propose and execute new ideas. Lowering the percentage of the population that consists of productive workers (and thus increasing pressure on those workers) seems likely to increase resistance to making the economic sacrifices necessary for addressing climate change.

On the flip side, I would assume that the persistence of reduced fertility rates is the result of the continuance of the factors that led to them in the first place, rather than an irreversible consequence of rates dipping below replacement value. Therefore, it seems this issue can be deferred until we see improvement on climate.

NickLaing @ 2025-07-01T12:53 (+4)

Depopulation is Bad

I don't think a modest reduction in population is bad in the medium term - I think AI is likely to compensate on the economic growth front, which would be my biggest concern. I think less people might give us a bit more runway on climate change. I don't buy the climate change section above, and this statement "Reducing birth rates now doesn’t reduce emissions in the next 25 years" is factually wrong I think. Why would it not? There's decent evidence that families carbon consumption rapidly increases after having a kid (buying more stuff, driving more, bigger houses)

I'm not sure of the definition of "depopulation" though. I definitely don't think rapidly falling populations are good either. I think this article predicts too far into the future though some weird doomer conclusions - ironically it feels similar to environmental doomerism in a way. I think If populations dramatically drop and immigration doesn't compensate, I think states will just heavily incentivise having more kids and likely solve the problem. I don't think that's necessary at the moment.

Obviously I'm not the kind of utilitarian who thinks that more net-positive people automatically means a better world. Fair enough if you are - in that case I think its hard to argue that more people isn't just better.

WillemW @ 2025-07-01T14:36 (+6)

You're right that families emit more carbon once they have a child. But I think it's worth pointing out that that the marginal carbon cost of additional children in a family is likely sharply decreasing. This is due to within-family economies of scale and because a lot of carbon is embodied in durable goods.

Richard Y Chappell🔸 @ 2025-07-01T15:57 (+5)

I'd guess that (for many readers of the book) less air travel outweighs "buying more" furniture and kids toys, at least. But the larger point isn't that the change is literally zero, but that it doesn't make a sufficiently noticeable change to near-term emissions to be an effective strategy. It would be crazy to recommend a DINK lifestyle specifically in order to reduce emissions in the next 25 years. Like boycotting plastic straws or chatgpt.

Updated to add the figure from this paper, which shows no noticeable difference by 2050 (and little difference even after that):

NickLaing @ 2025-07-01T17:18 (+2)

There have been a couple of studies showing that families with kids emit more than those without. Including this one from Sweden, where they emit 25 percent more.

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2020/04/200415152921.htm

That graph just shows that IF we manage to get emissions to plummet late in the century then a difference of 15 percent in population by 2100 might not make much of a difference to climate change. That's fine but there are many assumptions there.

I don't think having a few less people changes the game in climate change, but nor do I think it's very bad in other ways either.

Kevin Kuruc @ 2025-07-01T17:44 (+7)

I'm not sure that empirical data point about families is as telling as you think it is. Emissions are tied to total economic production. If total economic production doesn't go up, its hard to see how emissions go up much. The story by which an extra baby causes more economic production has to run through something like a demand-constrained economy (eg we're in a recession where more demand really does translate to more production).

In reality my best guess is that total production is ~unchanged when a new baby is born (or maybe even falls a bit, if a parent pulls back from the labor force), which means the additional purchases of a household with a baby are offset by slightly fewer purchases elsewhere in the economy. (Obviously once that baby is old enough to themselves work, that does increase production and emissions).

Zlatko Jovičić @ 2025-07-01T13:33 (+3)

Depopulation is Bad

Since I believe that humans have positive both instrumental and intrinsic value, I believe that depopulation in principle is bad, because if it's an entrenched long term trend, it would lead towards extinction. That being said, short term population decline is not necessarily the worst thing in the world, and could even be beneficial in certain extreme scenarios, such as severely overpopulated and resource depleted world, which I don't believe to be the case for our world.

Regarding instrumental value - I think we have a potential to have an extremely positive instrumental value in the Universe. If things go in a proper direction we could populate the Universe with sentient beings who live in utopian conditions. We could create digital worlds also filled with beings who live in delightful conditions. We definitely have potential for this, and I believe we have enough wisdom to actually achieve it. Not achieving this would be, as Bostrom points out, an astronomical waste. Right now we're the only known species with such potential.

On the other hand we're also causing a lot of farm animal suffering (but perhaps we're also reducing wild animal suffering even more), and there's a risk that we could export suffering to other worlds in the Universe, which would be astronomically bad.

But none of this is given or guaranteed. It depends on us. We have agency. Since we have agency, we can use this agency to produce enormous amounts of positive value both for ourselves and other sentient beings. So, I root for us, and I believe that we can and we should fulfill our potential for doing good.

Regarding intrinsic value - I also believe we have positive intrinsic value. Most of people are glad that they are alive, and they always seek to prolong their life if they can. That's the default attitude of most of the people towards life. Not only is life filled with many pleasures (food, music, art, sunsets, reading, philosophy, friendship, love, sex, etc...) but we find many aspects of it meaningful. Even our struggles and challenges can sometimes be seen as meaningful, such as in case of mountain climbing or marathon running. This, of course, is not to say that suffering is good - the types of suffering that can be "good" and meaningful are very rare and very specific, and generally mild. (Very few people would consider marathon running to be torture)

Now to go back to depopulation itself. By default it's bad. But it's not only bad because it reduces population, but it's also bad because it's a symptom of dysfunctional society in which people struggle to fulfill one of their most basic biological functions, to reproduce. There must be something deeply wrong about society in which people struggle to reproduce. Sub-replacement fertility is one of the symptoms of such social pathology.

In my opinion, for a society to be considered healthy, it must have at least stable population. Growth isn't the prerequisite for health of society, but stable population is.

The only exception to that rule would be an extremely overcrowded world in which people intentionally and consensually try to reduce their numbers by procreating less, until they reach a sustainable population. But that's an exception.

As a rule, depopulation is pathological, especially if it's unintentional, which I believe is the case in our world.

I also believe that recognizing depopulation as a symptom of social pathology could be a starting point in our efforts to improve our societies - not only in order to bring TFR above 2.1 again, but also for its own sake (as everyone prefers to live in a healthier society)

calebp @ 2025-07-02T08:23 (+2)

Depopulation is Bad

Though I don’t think it’s as big a deal as x-risk or factory farming. Main crux is probably the effect on factory farming, as is the case with many economic growth influencing interventions.

Paula Amato @ 2025-07-02T03:30 (+2)

We have a poor track record for predicting the impact of long term population changes e.g. the Population Bomb (Ehrlich).

The consequences of trying to control reproduction (especially women’s) are historically bad e.g. China’s one child policy.

What is the evidence that fertility rates won’t spontaneously reverse at some point, at least to replacement levels, even without incentives or restrictions on reproductive autonomy?

Why not concentrate on adapting to a lower population instead? E.g. increase productivity, automation, increased healthspan, etc.

I am skeptical of surveys that ask people “how many children they want.” Does this desire change over time depending on the age of the respondent? I think this needs to be qualified - under what certain circumstances would one want to have their ideal number of children? I.e. adequate resources including for child care, a stable partnership or community, no career penalty for women, etc. The answers to the latter question are likely to yield more insight to potential addressable solutions.

Most species go extinct within 1 million years or “speciate” into a different species eventually. Why should humans be different?

drbrake 🔸 @ 2025-07-03T18:02 (+1)

Depopulation is Bad

There are some realities about the problems caused by populations of the size we have now that simply cannot be "technologied around". The wealth of the world is profoundly unequally distributed and if we address this, overall consumption would radically increase as would the burden on the planet's resources. And there are limits to our ability to move around and find space for this many people to live (mainly in cities) in a comfortable way. Population decline needs to be managed to ensure it does not happen too quickly for our systems to cope and will eventually need to be encouraged to "level out", but only once we have established a path is set towards a human population which can live without overstraining the planet's finite resources. We have been fairly fortunate that for the most part our productive capacity has more than matched our population growth but we have no convincing guarantee that this would continue indefinitely while reducing ecological damage at the same time.

Bary Levy @ 2025-07-03T08:07 (+1)

Depopulation is Bad

A larger population has network effects: scientific progress is faster because a discovery by one person affects the entire population, economies of scale allow for better standards of living. The market is more efficient, which makes society as a whole more resilient to adverse events (e.g. during covid masks and vaccines were produced en masse very rapidly)

Manuel Del Río Rodríguez 🔹 @ 2025-07-02T18:28 (+1)

Depopulation is Bad

I mildly agree that depopulation is bad, but not by much. Problem is I just suspect our starting views and premises are so different on this i can't see how they could converge. Very briefly, mine would be something like this:

-Ethics is about agreements between existing agents.

-Future people matter only to the degree that current people care about them.

-No moral duty exists to create people.

-Existing people should not be made worse off for the sake of hypothetical future ones.

I don't think there's a solid argument for the dangers of overpopulation right now or in the near future, and I mostly trust the economic arguments about increased productivity and progress that come from more people. Admittedly, there are some issues that I can think of that would make this less clear:

-If AGI takes off and doesn't kill us all, it is very likely we can offshore most of the productivity and creativity to it, denying the advantage of bigger populations

-A lot of the increase in carbon emissions come from developing countries that are trying to increase the consumer capacities and lifestyle of their citizens. If scientific breakthroughs do not allow for progress, more people with more Western-like lifestyles will make it incredibly difficult to lower fossil fuel consumption, so if technology doesn't make the breakthroughs, it makes sense to want less people so that more can enjoy our type of lifestyle.

-Again, with technology, we've been extremely lucky in finding low hanging fruit that allowed us to expand food production (i.e., fertilizers, the Green Revolution). Again, one can be skeptic of indefinite future breakthroughs, which could push us down to some Malthusian state.

- Do people, on average, have positive or negative externalities (instrumental value)?

I imagine both yes. Most current calculations would say the positive outweigh the negative, but I can imagine how this can cease to be so.

- Do people's lives, on average, have positive intrinsic value (of a sort that warrants promotion, all else equal)?

Can't really debate this, as I don't think I believe in any sort of intrinsic value to begin with.

Picklehead @ 2025-07-02T17:50 (+1)

Depopulation is Bad

The population of an intelligent species is broadly correlated with the power of the species as a whole (think: rate of scientific progress), and thus its ability to realize its moral values.

In all but the most pessimistic cases, this outweighs any negative externalities of an increasing population: those concerned about humanity's contributions to animal suffering, for example, might imagine a future where we use our power to develop a way to eliminate natural predation (e.g. using lab-grown meat to feed carnivores), or autonomously deploy anaesthetics in the wild.

Yes, there might be short-term moral costs on the way to power. But stepping back to see the vast upside it will surely bring, I have to conclude that depopulation is bad—even if we ignore the (potential) inherent value of an additional human life!

MattJ @ 2025-07-02T17:29 (+1)

The “depopulation bad” framing - while helpful for engagement - misses key longtermist concerns in my opinion. The real question isn’t just how many people exist—but whether humanity (and other life) can flourish sustainably within planetary boundaries.

We’re already in ecological overshoot, degrading biosphere systems essential to all sentient life. Climate change is just one facet of a more complex set of systems facing challenges. A smaller, well-supported population—achieved via voluntary, rights-based policies—could reduce existential risk by stabilizing Earth’s life-support systems, supporting biodiversity, and improving welfare per capita.

Yes, demographic decline poses economic and institutional challenges. But these are solvable. Civilizational collapse from ecological breakdown is not.

Optimizing for total population without sufficient ecological resilience risks long-term value. We should aim for a population trajectory that preserves planetary habitability over the long run.

Thanks for the discussion!

M

Damilare @ 2025-07-02T15:12 (+1)

Depopulation is Bad, because it has a negative impact, sociall and economically. But we should try to avoid over population at the same time by regulating child birth.

mustaphasharif @ 2025-07-02T14:24 (+1)

Depopulation causes economic decline, labor shortages, and social strain as fewer workers support growing elderly populations. It leads to higher costs, reduced services, weakened national security, and declining community life, creating a cycle where more people leave and the situation worsens.

Jobst Heitzig (vodle.it) @ 2025-07-02T14:21 (+1)

Depopulation is Bad

It's kind of obvious to a sustainability scientist that fewer people eat up less of the remaining cake. It's a no-brainer. Only naive tech optimists can think some magical tech (maybe AI?) will allow us to decouple from resource use...

Zuzanna Matuszewska @ 2025-07-02T13:52 (+1)

Depopulation is Bad

Less people = less suffering, easier to divide resources, less strain on the planet

Miles Kodama @ 2025-07-02T13:42 (+1)

Depopulation is Bad

The only reasons I didn't vote farther to the right are (1) moral uncertainty, and (2) depopulation could interact with AI risk in ways that I only dimly understand.

Dave Cortright 🔸 @ 2025-07-01T23:13 (+1)

SummaryBot @ 2025-07-01T18:30 (+1)

Executive summary: This first part of a two-part review passionately argues that global depopulation poses a serious threat to human progress and well-being, emphasizing that more people mean more innovation, economic capacity, and moral value—while rebutting common concerns like climate change with the claim that technological solutions, not population decline, are what really matter.

Key points:

- Depopulation is an underrecognized existential risk: The world has passed “peak baby” and is on track for a steep population decline, which could lead to a premature end to humanity’s story if current fertility trends continue.

- Climate change won’t be solved by fewer people: Spears and Geruso argue that since we must decarbonize in the next few decades, depopulation occurring after 2080 is irrelevant or even harmful, as it reduces the capacity for innovation and infrastructure.

- Innovation is driven by population size: The book highlights how more people lead to more ideas, technologies, and economic specialization—benefits that shrink in a depopulated world, even if no one is exceptionally talented.

- People are not competitors for scarce resources—they are creators: The author pushes back on zero-sum thinking by emphasizing that having more people increases the chance that someone creates what you most value.

- Ethically, more good lives are better: The post endorses the principle that a world with more happy, flourishing people is better than one with fewer, so long as those lives are worth living.

- Debate should focus on externalities and intrinsic value—not coercion or racial anxieties: The author urges readers to steer clear of conflating concern about depopulation with reproductive authoritarianism or far-right ideology, emphasizing reproductive freedom and global well-being instead.

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.

Otto @ 2025-07-01T14:32 (+1)

Depopulation is Bad

Population has soared from 1 to 8 billion in 200 years and is set to rise to 10. There is no depopulation, there is a population boom. That population boom is partially responsible for the climate crisis, biodiversity loss, and many other problems. It would be quite healthy to have a bit more moderate amounts of people.

Plasma Ballin' @ 2025-07-01T15:37 (+7)

It's set to rise to ten and then fall precipitously. But even if it were the case that we are not on course for population decline, that wouldn't affect the question of whether or not population decline is bad. It would just mean we don't have to worry about it.

The results of a population collapse like what's being projected would probably be worse for society than climate change. But even if climate change is worse, depopulation won't help solve it, as the article mentions. We really should be looking for ways to go net-negative in the medium-term future, which will be easier with more people.