What we owe the future (Will MacAskill)

By EA Global @ 2020-06-05T19:36 (+14)

This is a linkpost to https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vCpFsvYI-7Y

In this 2020 talk at Harvard University, Will MacAskill makes the case for "longtermism" — which he describes as the biggest realization he's had in the past 10 years — and explains how those motivated by this cause can help.

Below is a transcript of Will's talk, which we've lightly edited for clarity.

The Talk

Hi. Thank you all for attending this lecture, and thank you so much, Professor Pinker, for inviting me to speak. I'm sorry that we are in trying times and I'm not able to be there in person.

Over the last 10 years, I've spent pretty much all of my time focused on this question of effective altruism: How can we use our time and money to do as much good as possible? In this lecture, I'm going to talk about what I regard as the most major realisation I've had over that time period.

[00:00:35] It's what I call “longtermism”, which I'll say is the claim that if we want to do the most good, we should focus on bringing about those changes to society that do the most to improve the very long-term future. The timescales involved here are much longer than people normally think about. I'm not talking about decades. I'm talking about centuries, millennia, or even more. And in this lecture, I’ll make the case for longtermism. I'm going to do so on the basis of four premises.

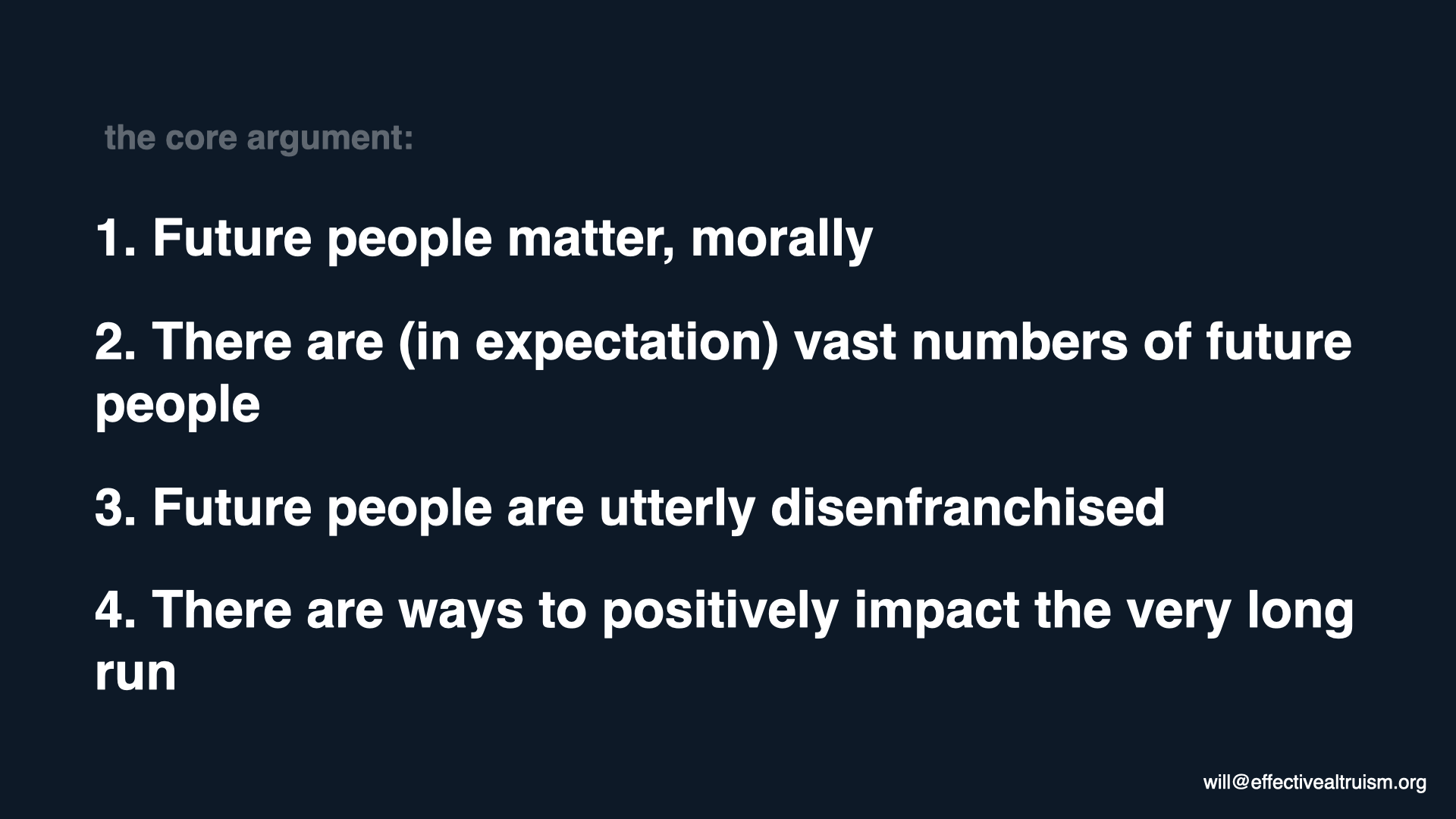

Four premises foundational to the case for longtermism

[00:01:09] So the first premise, I hope, is going to be relatively uncontroversial among this audience. It's the idea that future people matter, morally speaking. It doesn't matter when you're born; the interests of people in the future — in a century's time, a thousand year's time, a million year's time — count just as much, morally speaking, as ours do today. Again, I hope this is a relatively intuitive claim. But we can also conduct a little thought experiment to help show how intuitive it is.

[00:01:43] So imagine that you're walking on a hiking trail that's not very often used. And at one point, you open a glass bottle and drop it. It smashes on the trail, and you're not sure whether you are going to tidy up after yourself or not. Not many people use the trail, so you decide it's not worth the effort. You decide to leave the broken glass there and you start to walk on. But then you suddenly get a Skype call. You pick it up, and it turns out to be from someone 100 years in the future. And they're saying that they walked on this very path, accidentally put their hand on the glass you dropped, and cut themselves. And now they’re politely asking you if you can tidy up after yourself so that they won't have a bloody hand.

Now, you might be taken aback in various ways by getting this video call, but I think one thing that you wouldn't think is: “Oh, I'm not going to tidy up the glass. I don't care about this person on the phone. They're a future person who’s alive 100 years from now. Their interests are of no concern to me.” That's not what we would naturally think at all. If you've harmed someone, it really doesn't matter when it occurs.

[00:03:06] So that's the first premise. And where it gets real bite is in conjunction with a second empirical premise: that there are, in expectation (so not certainly, but with a significant degree of probability) vast numbers of future people.

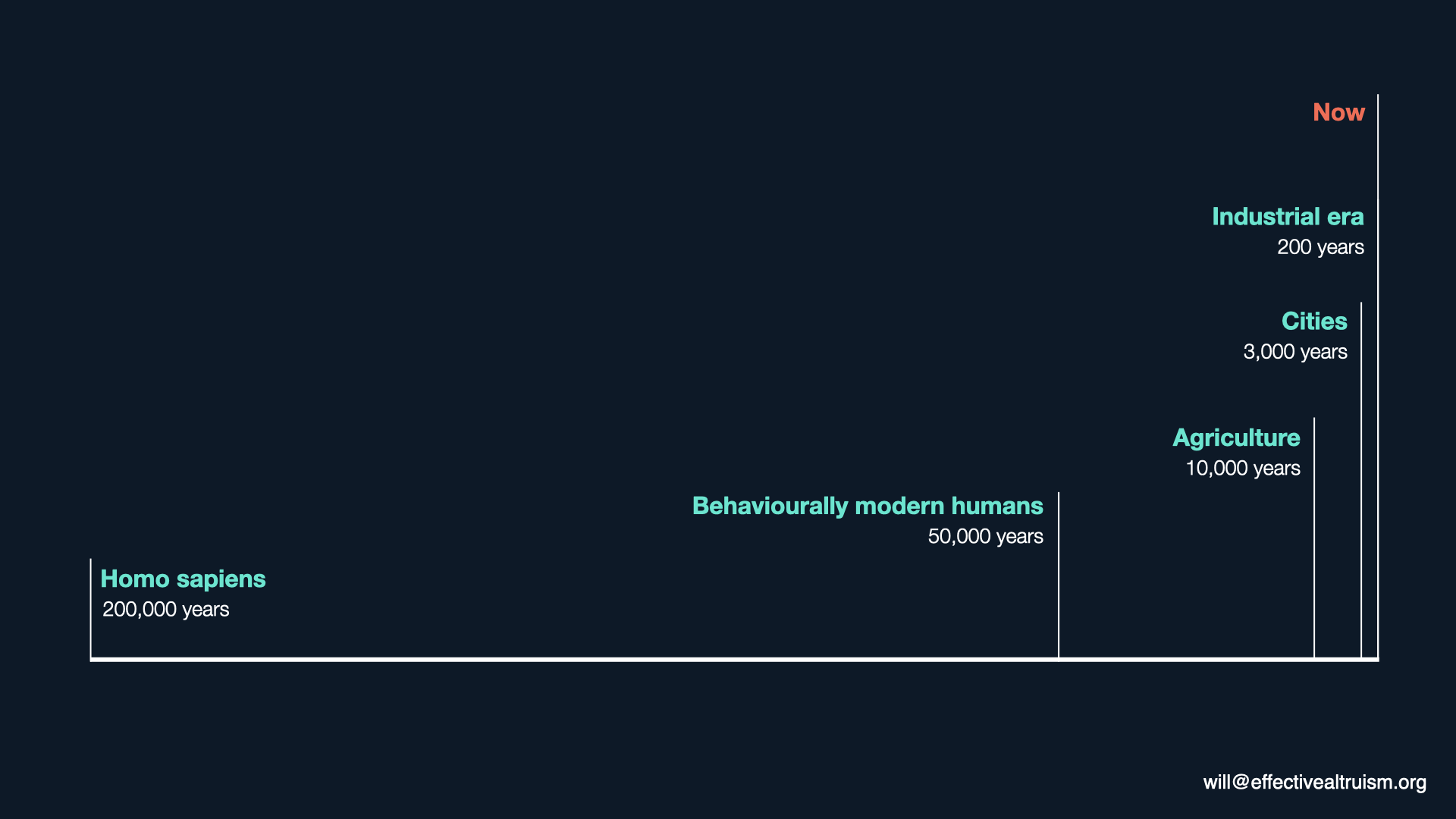

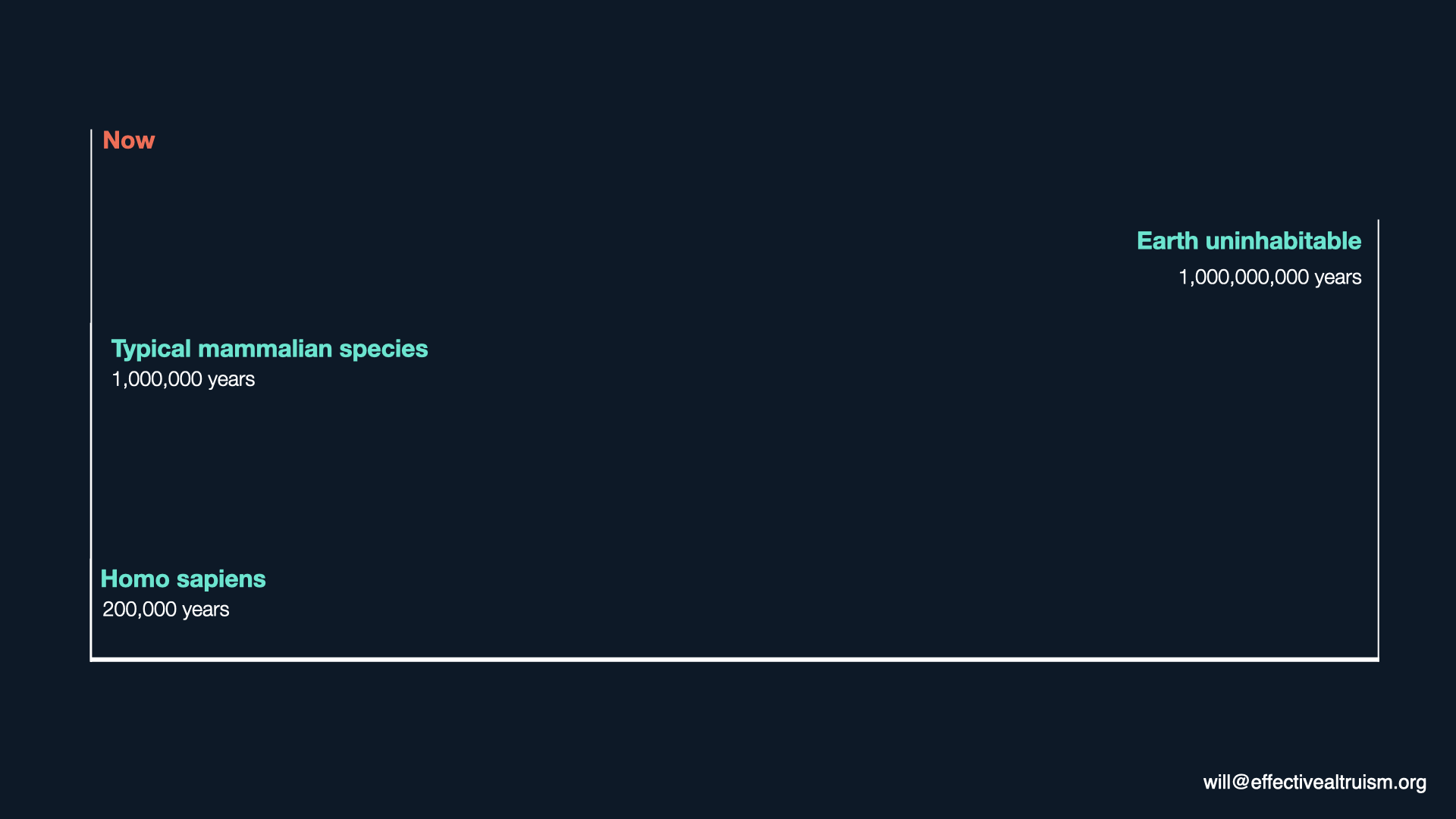

To see this, we can consider the entire history of the human race. Homo sapiens came on the scene about 200,000 years ago. We developed what archaeologists regard as behavioural modernity about 50,000 years ago, developed agriculture about 10,000 years ago, the first cities a few thousand years ago, and just 200 years ago — really the blink of an eye by evolutionary time scales — entered the industrial era.

[00:03:58] That's how much time is behind us. But how much time is there to come?

Well, the typical mammalian species lasts about a million years, suggesting we still have 800,000 years to come. That's the estimate for the typical mammalian species, but Homo sapiens isn't the typical mammalian species. We have 100 times the biomass of any wild, large animal to have walked the earth, across an enormous diversity of environments. And most importantly, we have knowledge, technology, and science.

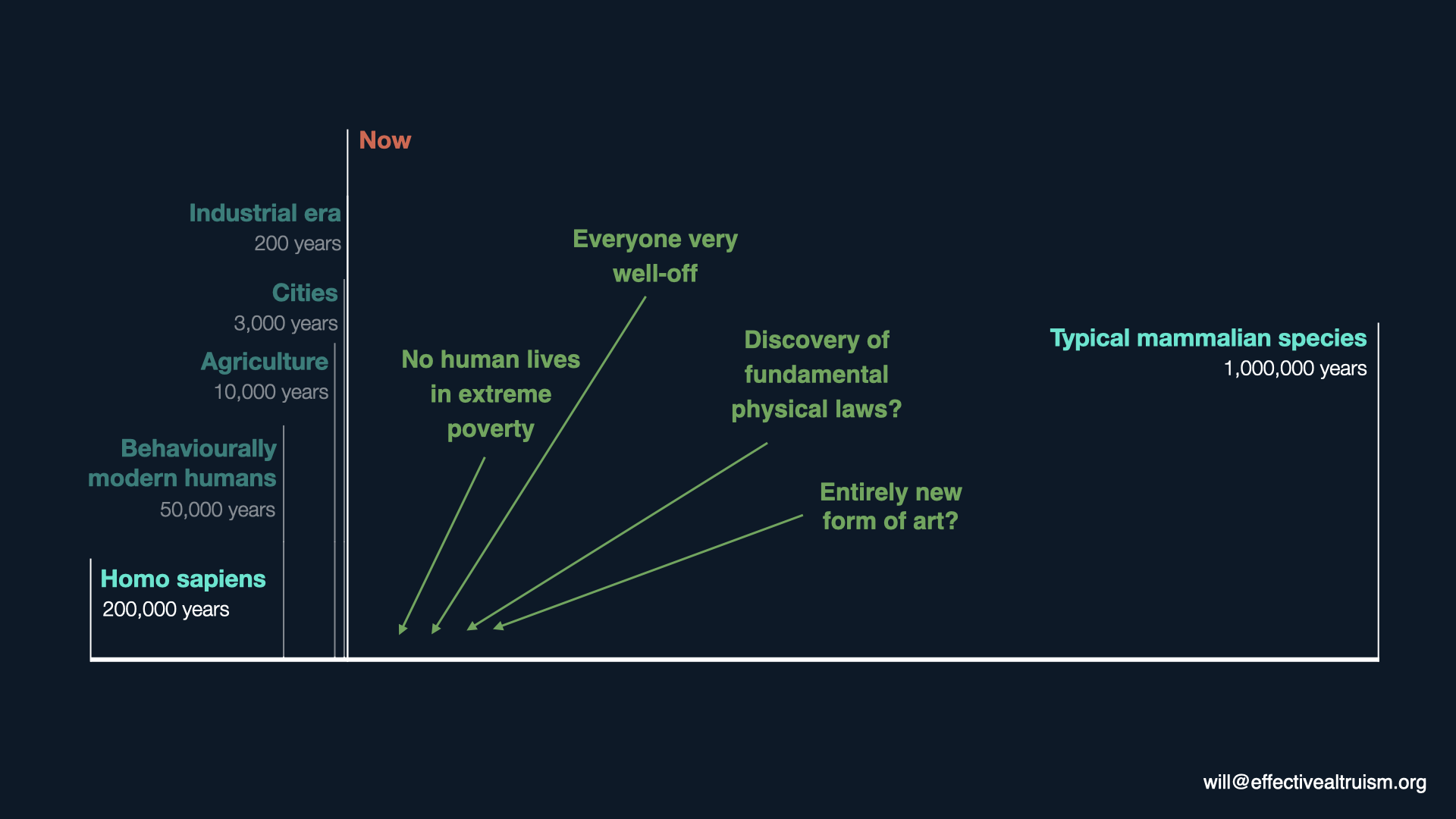

[00:04:35] There's really no reason why, if we don't cause our own untimely end, we couldn't last much longer than a typical mammalian species. Earth itself will remain habitable for about a billion years before the expanding sun sterilises the planet.

And if someday we took to the stars, then we would be able to continue civilisation for trillions more years.

[00:05:07] What's important for this argument isn’t any of the particular numbers. It's just the fact that, based on even the most conservative of these estimates, the size of the future is absolutely enormous. The number of people who are yet to come is astronomical.

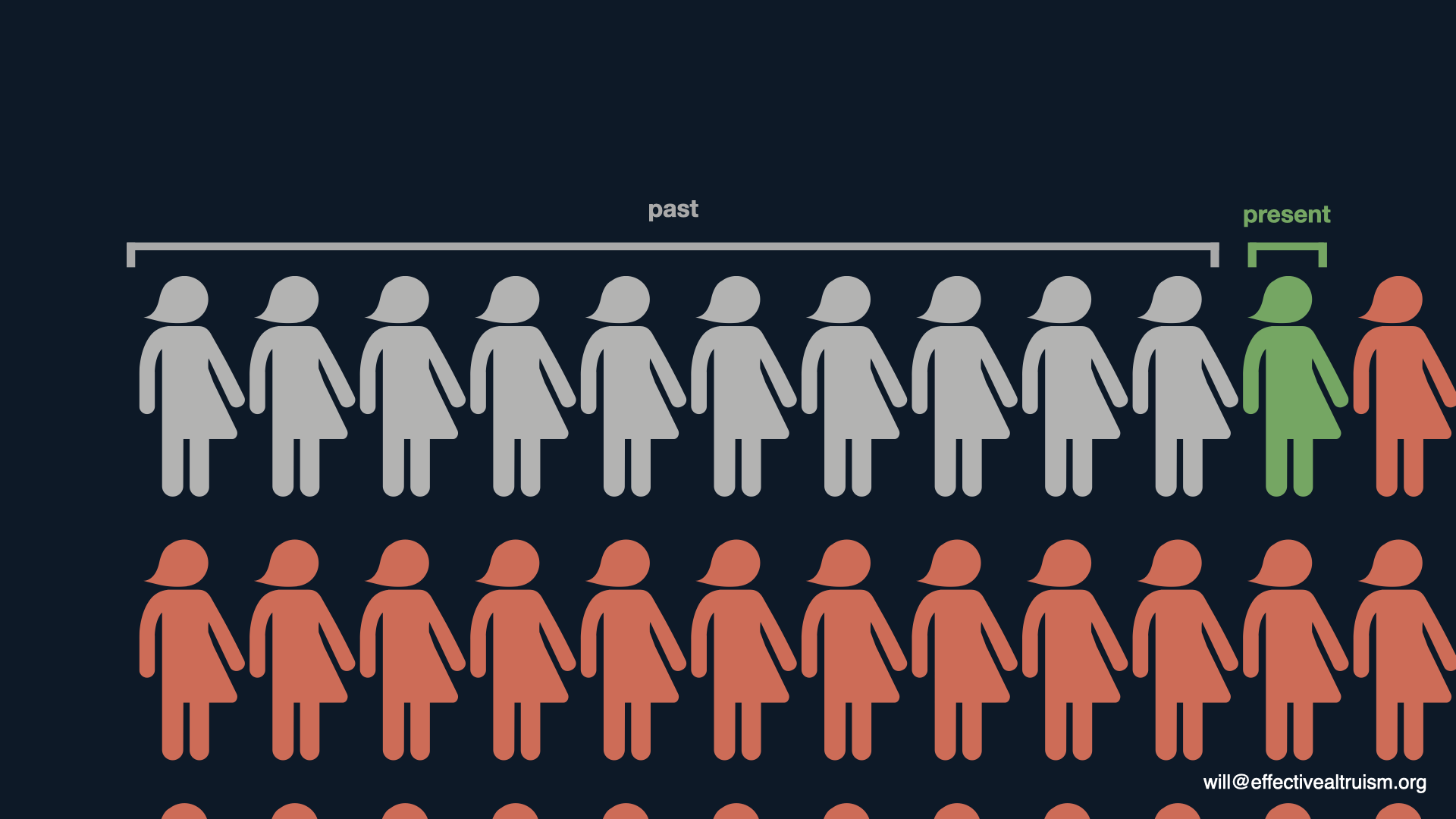

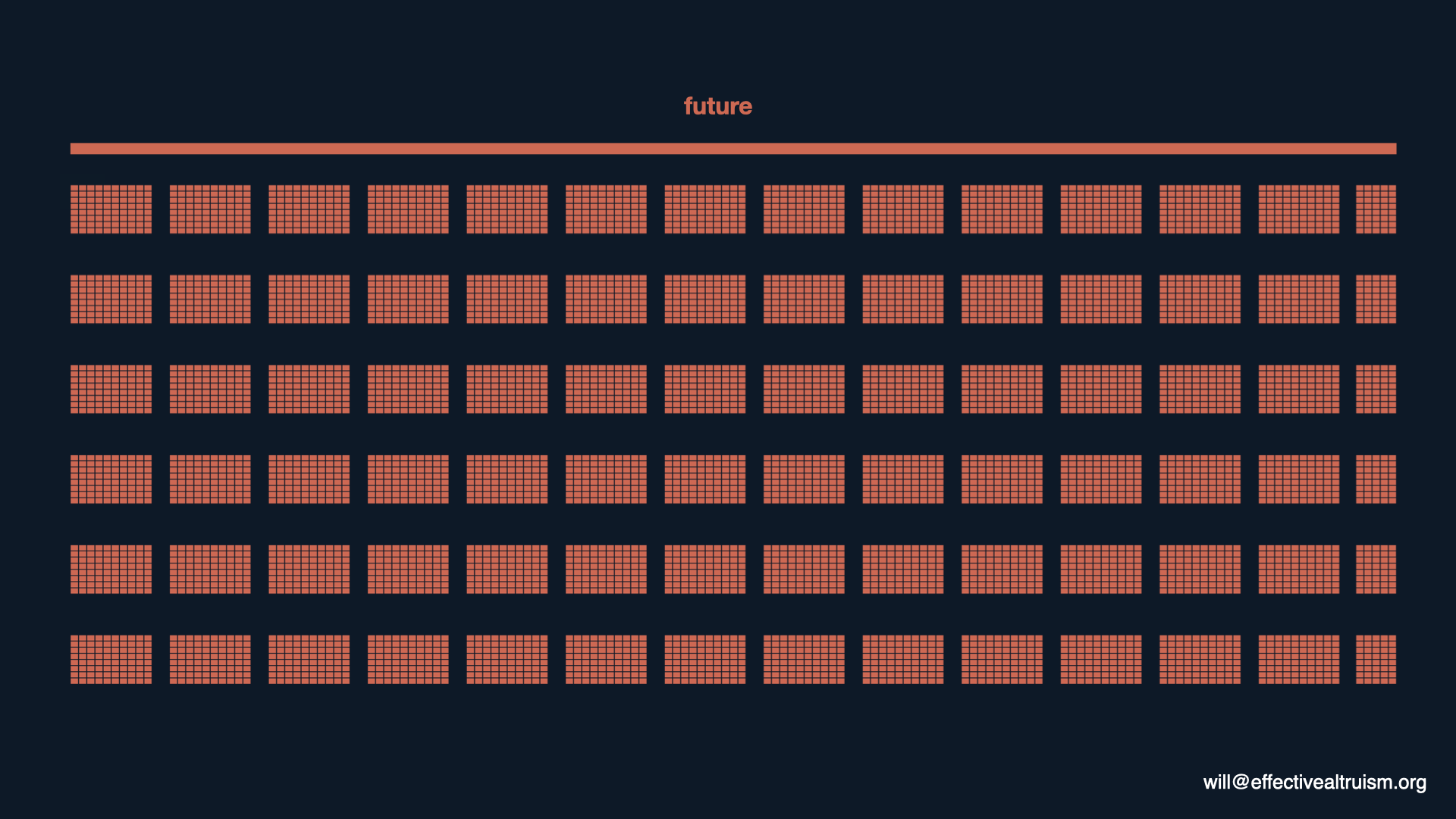

We can visualise this. Let's use one of these stick figures to represent approximately 10 billion people. So there have been about 100 billion people in the past. There are about eight billion people alive today. Even on the conservative end of these estimates, the number of people who are yet to come would outnumber us by thousands or even millions to one.

[00:05:52] So that's my second premise — that there are, in expectation, vast numbers of future people. And that's so important because, when combined with the first premise, it means that in the aggregate, future people’s interests matter enormously. Anything we can do to make future generations' lives better or worse is of enormous moral importance.

[00:06:15] The third claim is that society does not currently take those interests seriously. Future people are utterly disenfranchised. For example, they cannot bargain with us. It's not like those who will be harmed by our burning of fossil fuels and emissions of greenhouse gases can sue us, or send us a check for the liability.

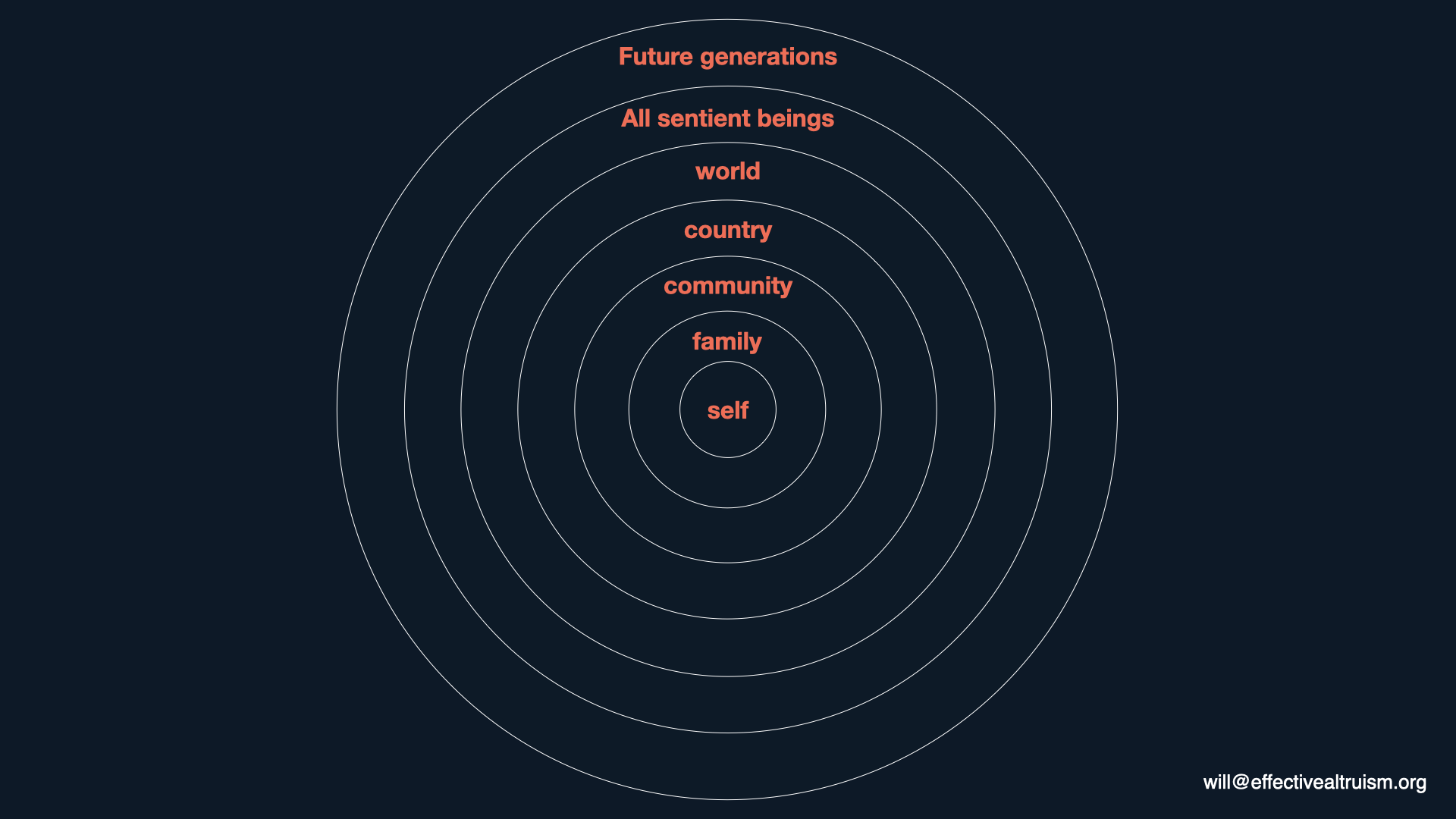

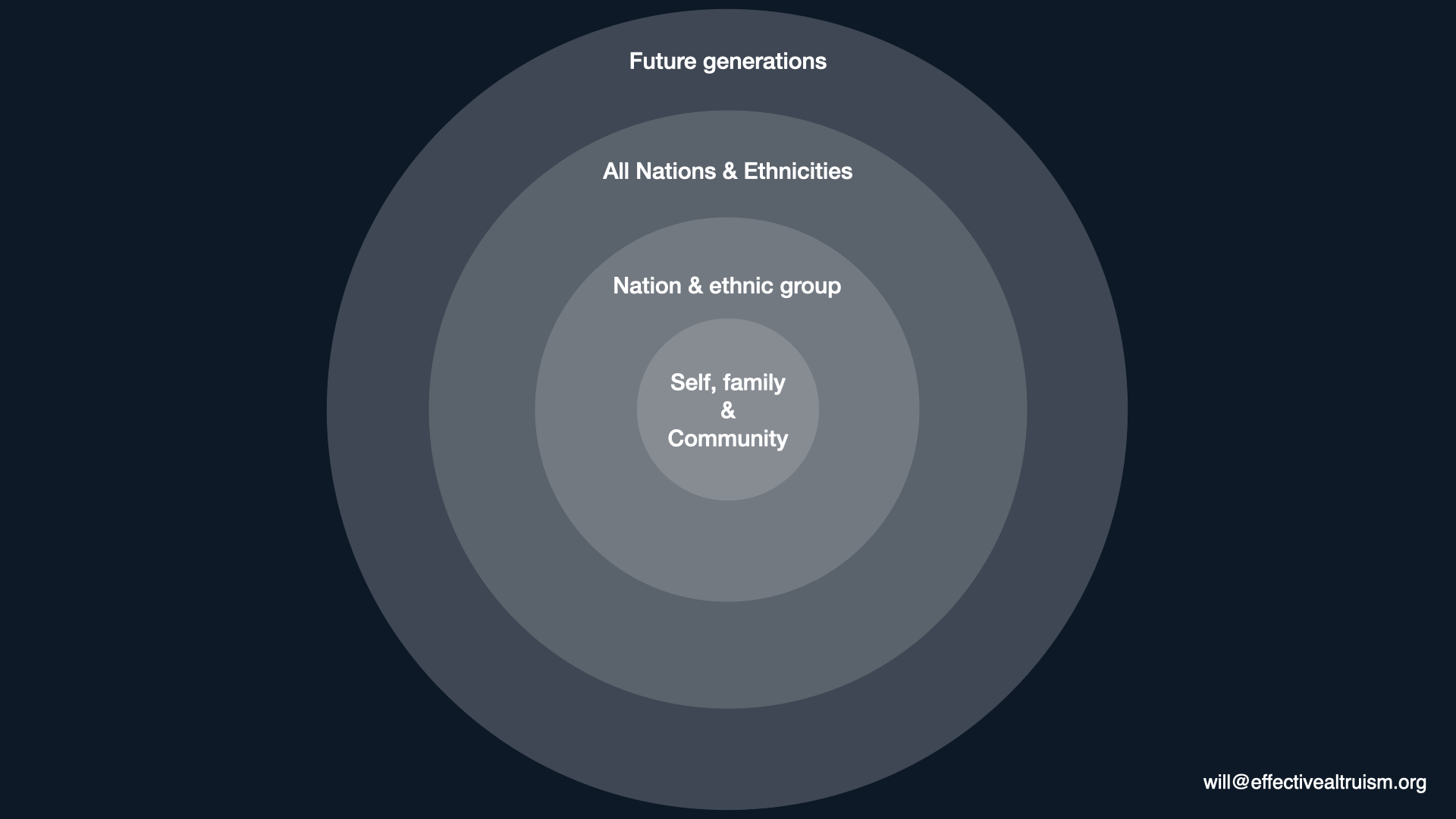

[00:06:42] More fundamentally, future people don't have a vote, so they can't affect the political decisions that we're making today that might impact them. Therefore, I think we can view concern for future generations as one step forward on the continuation of moral progress that we’ve seen for thousands of years. Peter Singer describes this as “the expanding moral circle”.

Perhaps in the hunter-gatherer era, our moral circle was confined just to ourselves, our family, and our community.

With the development of nation-states and religions, this expanded to concern for everyone of your nation, ethnic group, or religious group. In the last few centuries, this has expanded again. You start to take seriously the idea of cosmopolitanism — the idea that all nations and ethnicities, everyone in the world, is of equal moral value, no matter where they are or which country they’re born into.

[00:07:43] I think, then, that the final step in this progression is to care not just about everyone in the world, but everyone — no matter which generation they represent. And what we should be thinking is that it’s a great injustice that there are so many people who are yet to come, and who are entirely left out of the decisions we make, whether those decisions are in business, politics, or elsewhere.

[00:08:15] Those are my first three premises. I regard all of them as relatively uncontroversial.

I'll spend the rest of this talk on the final premise, which might be the most controversial. It's that there are ways, in expectation, to positively impact the very long run.

You might think that this is a very bold thing to think. You might think that it’s hard to predict events even a few decades out, let alone centuries or millennia in the future. But I think, as we'll see, we actually have good grounds for believing this. And even though it might seem like any effect we could have is very small, I think over the long run, those small effects can add up to an enormous effect overall.

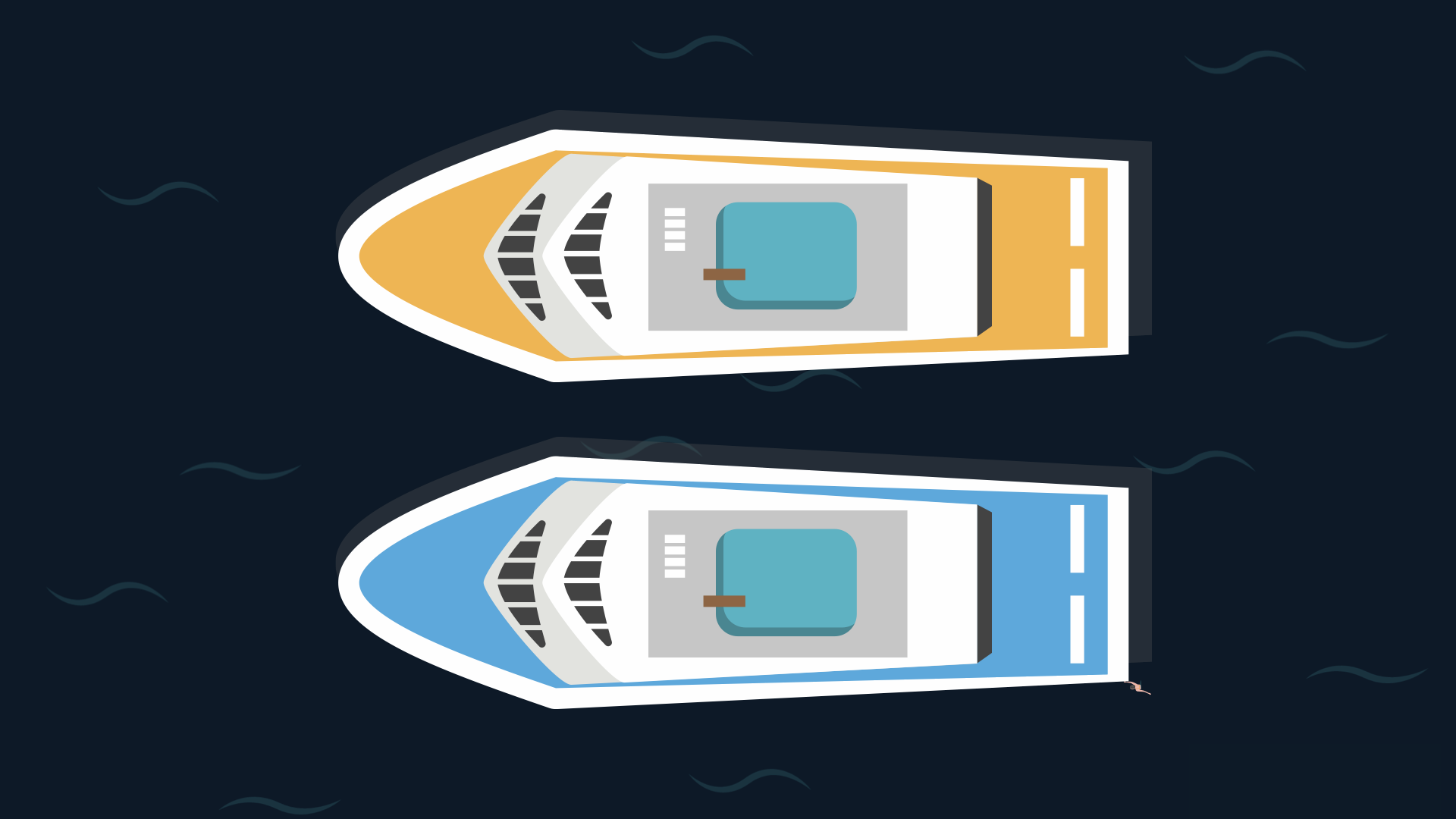

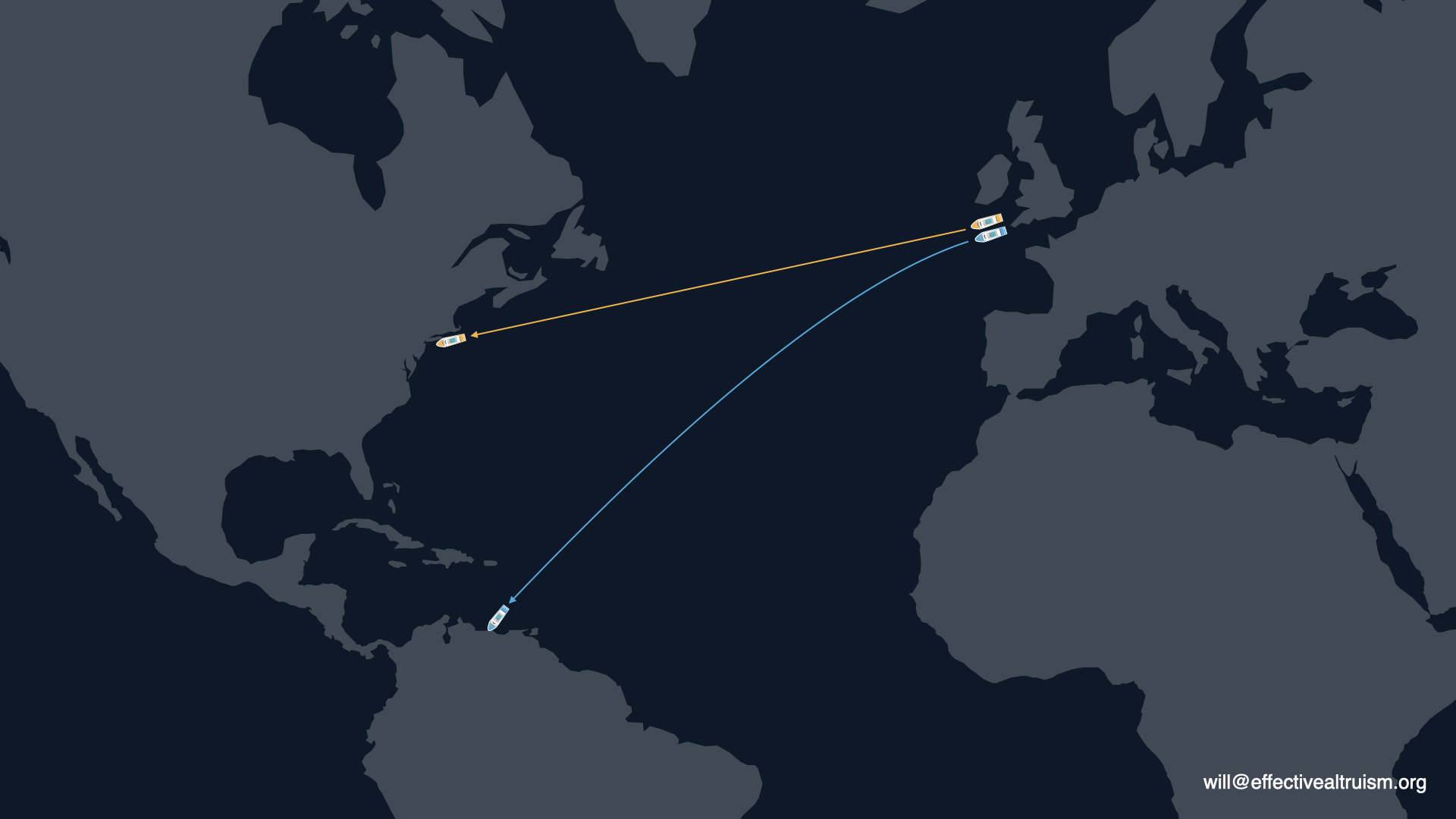

[00:09:07] The analogy I want you to have in mind is this: There's a cruise liner that's leaving from London and heading to New York. This cruise liner represents civilisation. And we [in the effective altruism movement] are just this little entity — a group of people trying to make a difference, like a swimmer trying to push on the cruise liner and alter its trajectory.

With such a small amount of force and such a large ship, you might think you couldn't possibly make a difference. But with about a day's worth of swimming and pushing on the ship (I asked some physicist friends to do the math on this for me), you could make it end up in Venezuela instead of New York.

Three categories of ways to influence the very long run

[00:09:59] I'm going to talk about three categories of ways in which we can influence the very long run. The first is the most familiar to you. It's climate change. I'm only going to cover that very briefly. Second is the idea of civilisational collapse — some very negative event that could result in us going back to the industrial era and never recovering. I'll particularly focus on how that could happen as a result of war or pandemics. Finally, I'll talk about values change.

Climate change

[00:10:38] Climate change is the future-impacting issue that's obviously most well-known today. The thing that's striking about climate change, though (if you look at the economic and policy evaluation), is that most evaluations approximate impacts in the next century. They tend not to look at impacts later than that date.

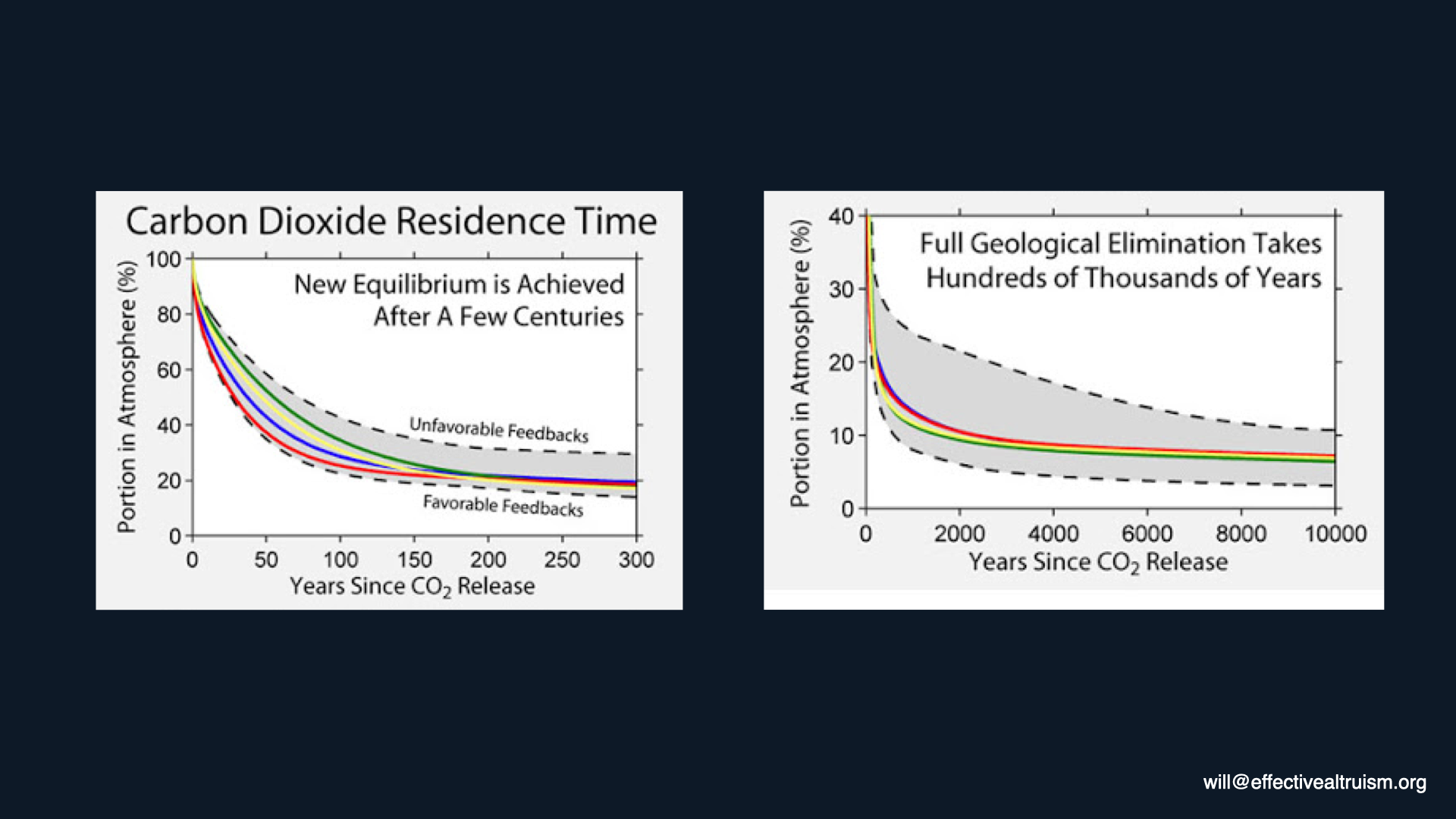

[00:11:02] From a longtermist perspective, that's completely unjustified. The CO2 that we emit currently has an average atmospheric lifetime of 30,000 years. So even though most carbon dioxide is reabsorbed into the oceans after a few centuries, there's a very long tail. Even after 100,000 years, 7% of the CO2 that we emit will still be in the atmosphere.

[00:11:28] Also, there are many long-lasting impacts of climate change. The irrevocable changes include species loss; climate change will undoubtedly lead to the loss of many types of species. If we don't preserve their DNA, then we can't get them back.

[00:11:50] Second is the loss of coral reefs. It's likely that coral reefs will die off, even just within a few decades, from existing climate change. It takes tens of thousands of years for these to replenish themselves.

[00:12:04] Another category is the loss of ice sheets and sea-level rise. Even if we were to entirely stop fossil fuel emissions, fossil fuel burning, and carbon dioxide emissions today, sea levels would continue to rise for thousands of years. The Greenland ice sheet is possibly already past the tipping point. Certainly, if we get to three degrees of warming, then there will be this very slow, positive feedback loop, where the melting of the Greenland ice sheet leads to more melting, which leads to more melting. And over the course of about 1,000 years, it will entirely melt away, raising sea levels by about seven metres.

[00:12:46] The final category is the impact on us. We can see that in terms of impact on the economic growth rate. Economists normally think of climate change as just reducing our level of economic productivity, rather than impacting how fast we're growing. But recent analyses have called that assumption into doubt. This makes a really big difference. So even the difference between the economy growing at a rate of 2% per person per year and 1.8% per person per year as a result of climate change, will become the equivalent of a catastrophe that wipes out half of the world's wealth in a few centuries.

[00:13:32] I'm not going to dwell on this too much, but it's pretty clear that, from a longtermist perspective, climate change is among the very most important issues.

Civilisational collapse

[00:13:46] The second category I want to think of is civilisational collapse, whereby an event has an extremely negative impact on civilisation that could potentially persist indefinitely.

This could happen in one of two ways. At the most extreme, if there was an event that literally killed everyone on Earth, then Homo sapiens would be like those species that we're driving to extinction. Once we go extinct, that's not something we can come back from. Or if the catastrophe put us back sufficiently far — to a kind of pre-industrial state — perhaps that could be a significant enough catastrophe that we would not be able to recover.

[00:14:35] With this category, looking at history is the most natural way to explore answers to the question “What are the most likely ways that civilisational collapse could occur?”

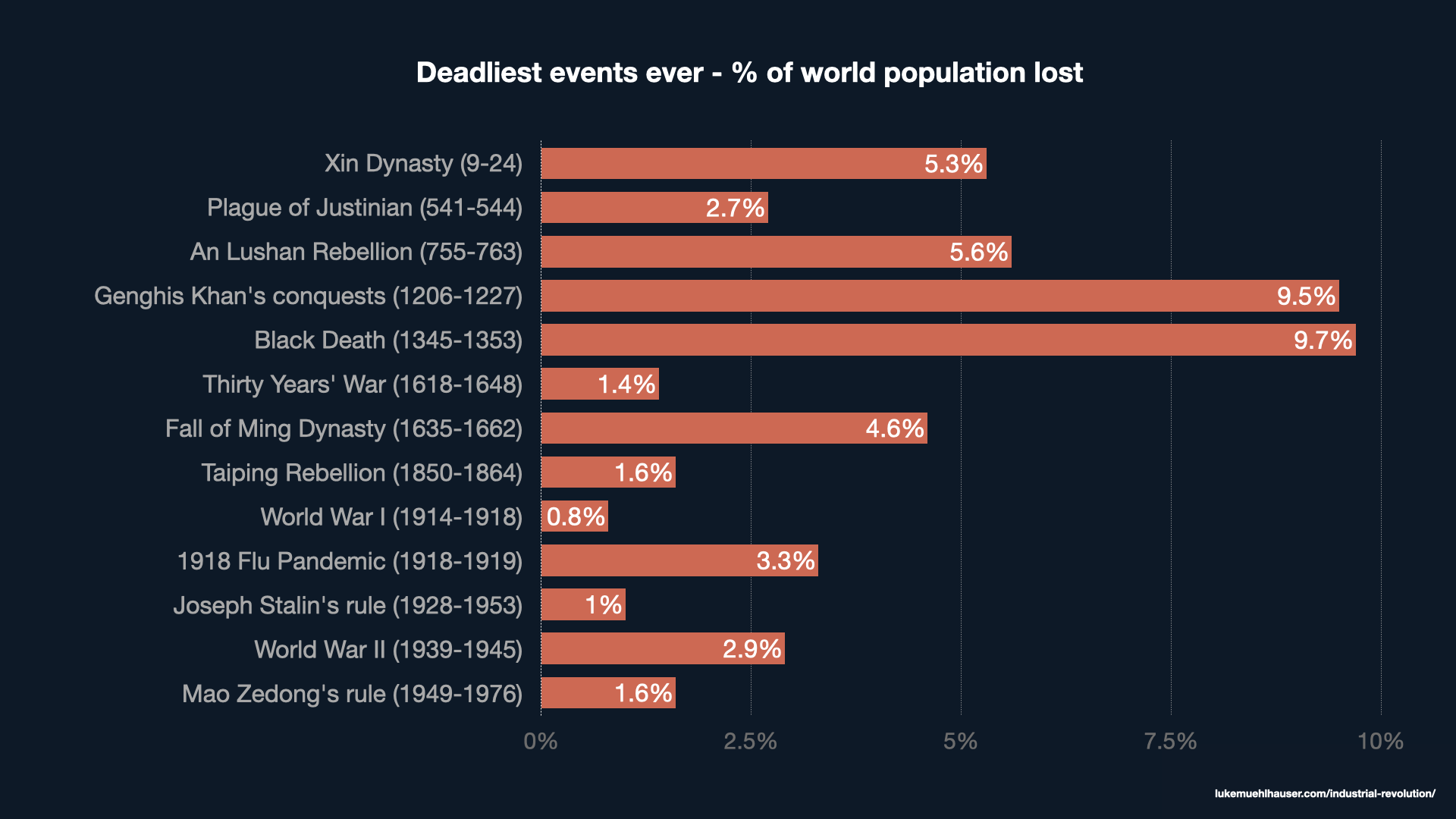

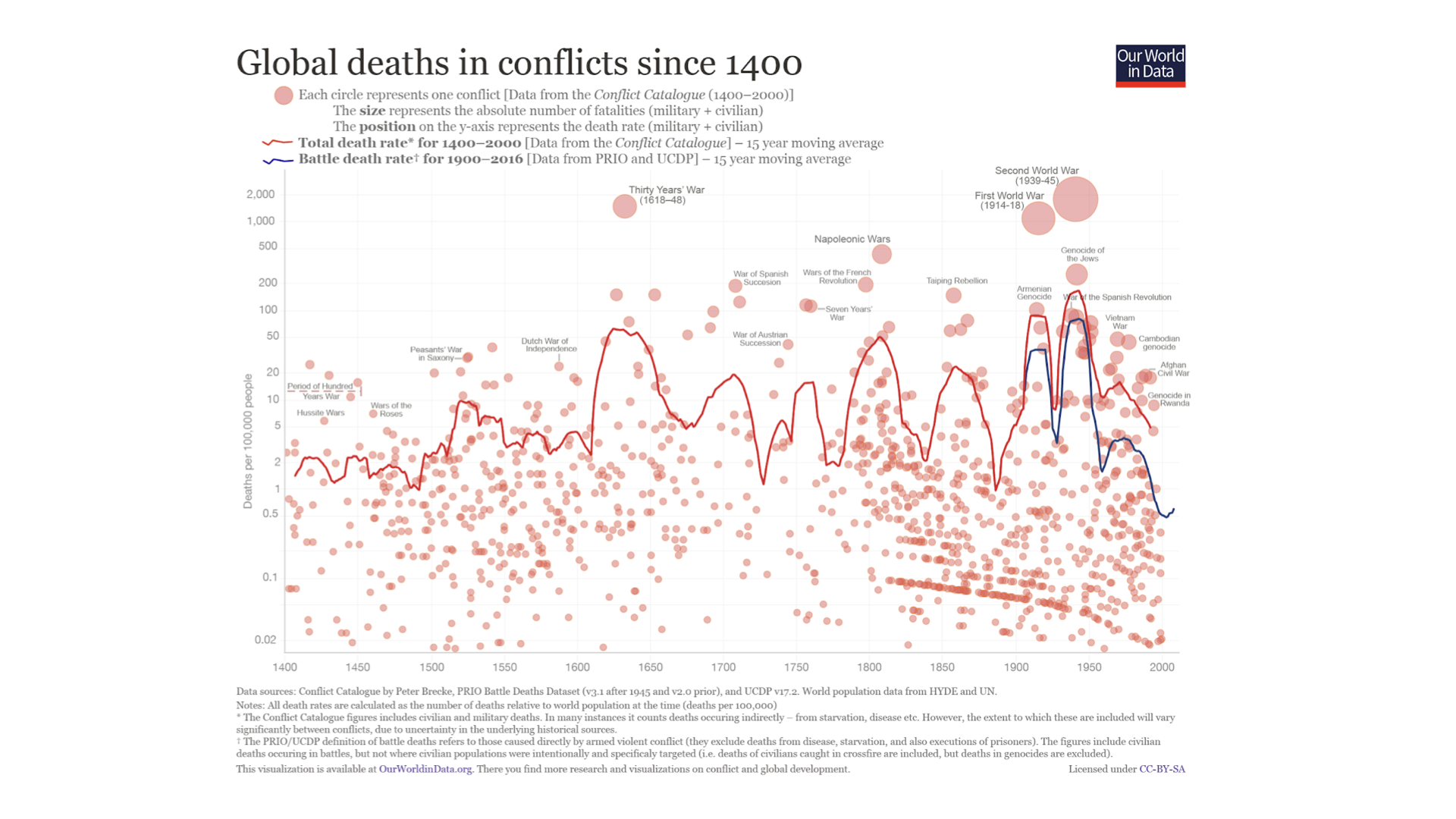

If we look at the deadliest events ever — the worst things that have ever happened — as measured by death count (and this is the death count as a proportion of the world's population), it's actually quite striking.

Two categories really leap out. The first is war. The second is pandemics. Genghis Khan was responsible for killing almost 10% of the world's population. So I'm going to use these as the two possible causes of civilisational collapse that could occur within our lifetimes, or within the zone of influence. I want to emphasize that I'm not claiming that these are likely — just that the consequences would be so enormous that even a low probability means that we should be paying close attention.

[00:15:43] The first category is war. It may seem unimaginable that there could be another war between great powers of the magnitude of World War I or II — or even greater — within our lifetimes. After all, we've lived through what historians call “the long peace”: 70 years of unusual levels of peace and stability on an international level.

[00:16:10] But I don't think we can be too optimistic; I don't think we can rule out the possibility of another war between great powers, perhaps between the US and China or the US and Russia, in our lifetimes. Part of the reason for this is just that war between the major powers in the world is absolutely a fixture of history. And if you look at how the death rate from war over time has changed, there's not much of a trend.

It looks pretty flat. The reason it goes up and down is only because the death toll from wars is driven by the very worst ones. This is what statisticians call a “power-law distribution” or “fat-tailed distribution”. We’ve had 70 years of peace and I really, really hope that continues. I hope it’s due to deep structural factors. But from a statistical perspective, we can't rule out that we haven't just gotten lucky.

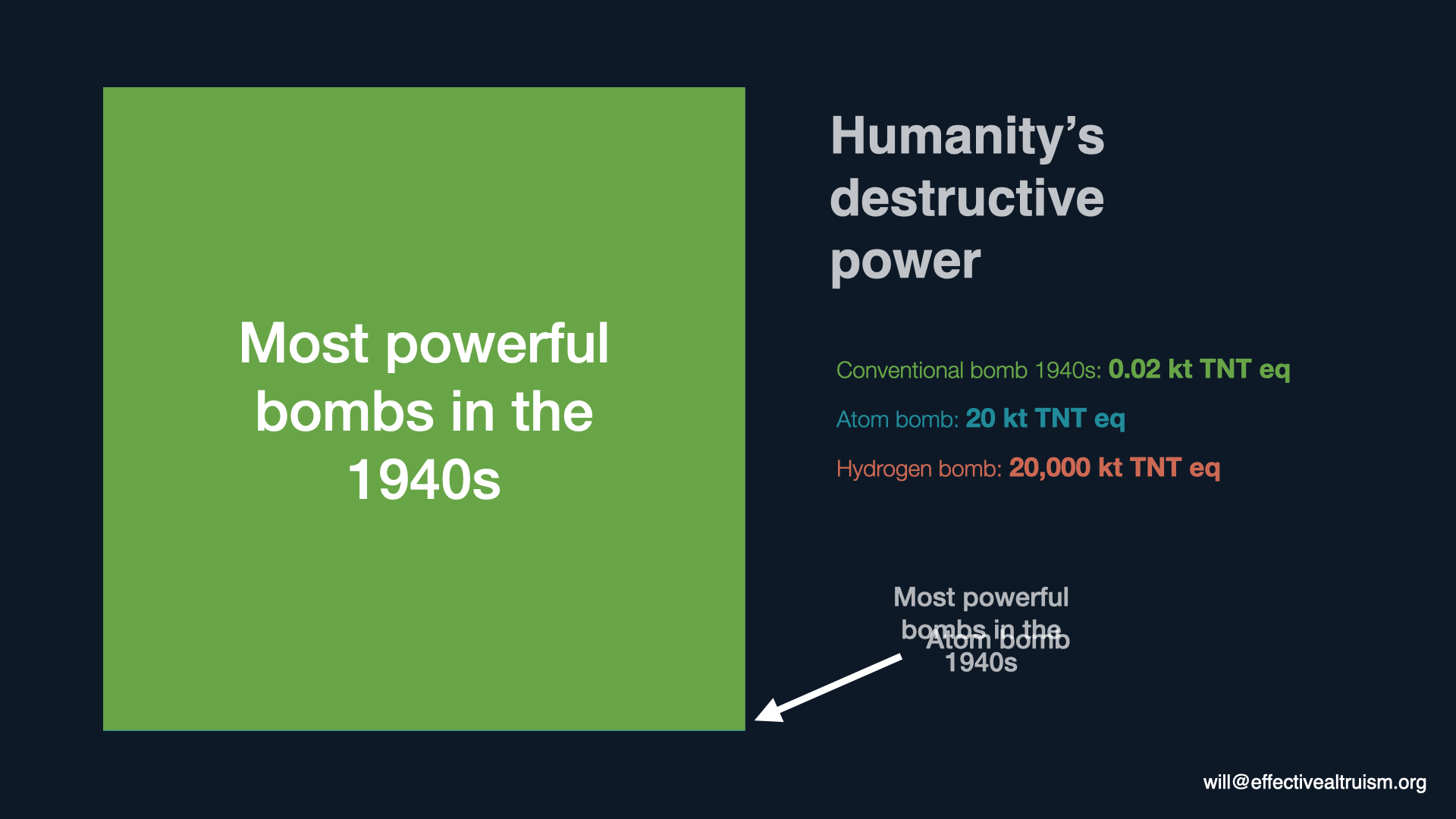

[00:17:18] This becomes particularly important because, since 1945, the potential destructiveness of the worst wars has increased quite significantly. This is because of the invention of nuclear weapons.

In the 1940s, this green box represents the yield of a conventional bomb: 0.02 kilotons. When we invented the first atomic weapons, we developed weaponry that was a thousand times more powerful. And what is much less well-known is that the move from the atom bomb to the hydrogen bomb was just as great a leap forward in destructive power as the move from conventional weaponry to the atomic bomb.

So the atomic bomb was a thousand times more powerful than conventional weaponry. The hydrogen bomb was a thousand times more powerful again.

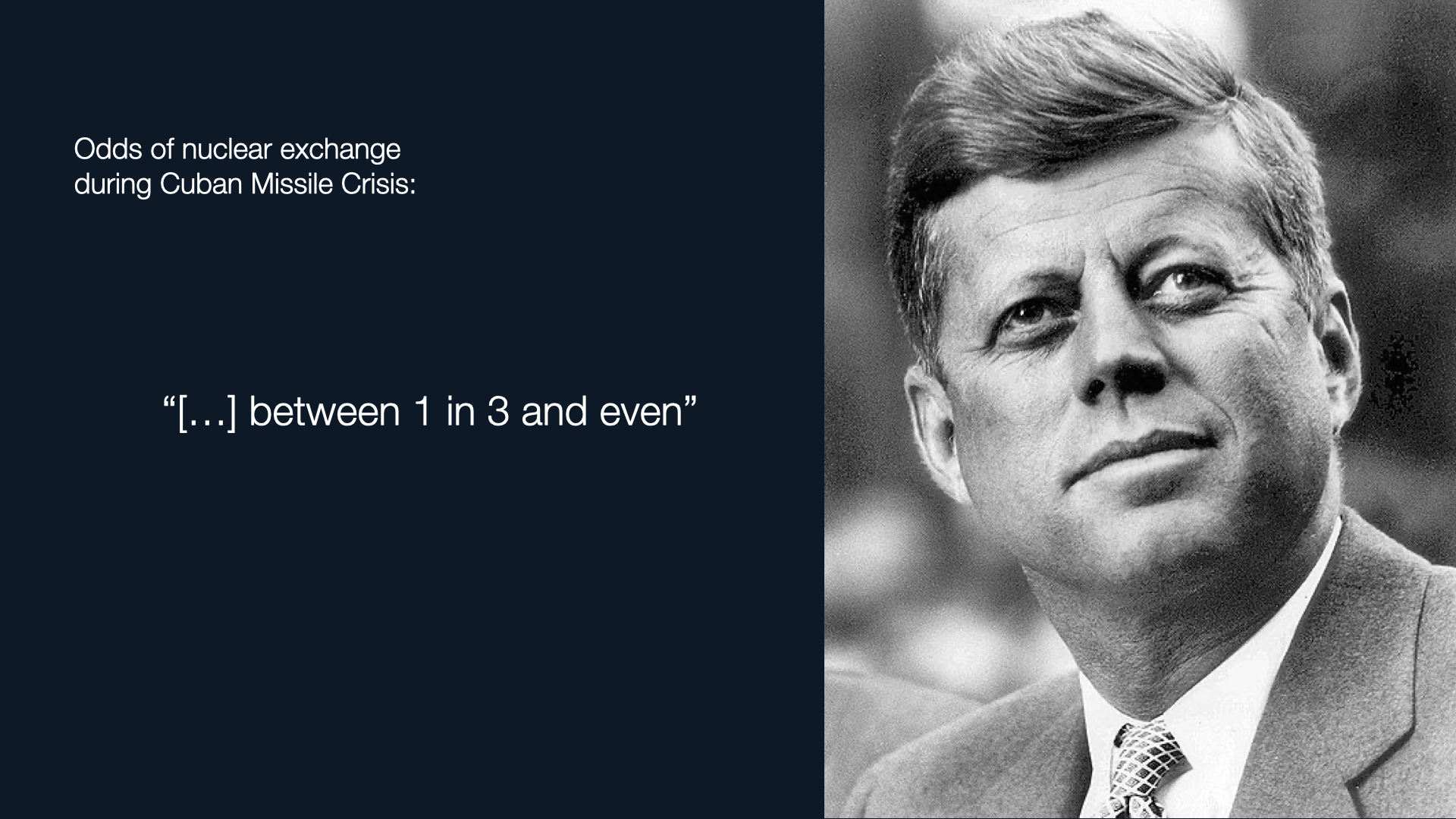

[00:18:17] We subsequently built many, many thousands of such weapons and still have many thousands. And we really did come close to using them. During the height of the Cuban Missile Crisis, John F. Kennedy, for example, put the odds of an all-out nuclear exchange between the US and USSR at somewhere between one in three and even.

If there were an all-out nuclear exchange, there's a significant probability (although not a guarantee) of nuclear winter, where temperatures would drop five to ten degrees for a period of about a decade. We really don't know with any degree of confidence what would happen to civilisation and society after that point. And this, of course, is a potential result with the weapons that we have today. Insofar as we're thinking about the events that might occur in our lifetimes over the next 40 years, we have to think about the next generation of weaponry, too. And I'll come to that in a moment.

[00:19:19] I think that the possibility of war in our lifetimes is potentially one of the most important events from a longtermist perspective.

The second category I'll talk about is pandemics, which is obviously very timely at the current moment. We in the effective altruism community have been championing the cause of pandemic preparedness for many years. It's very clear that we are not sufficiently prepared for a pandemic. That’s just a sad fact that is now quite evident. And pandemics are like wars in that they follow a fat-tail distribution, such that the worst wars are far worse than a typical war. The very worst pandemics are much, much worse than merely bad pandemics.

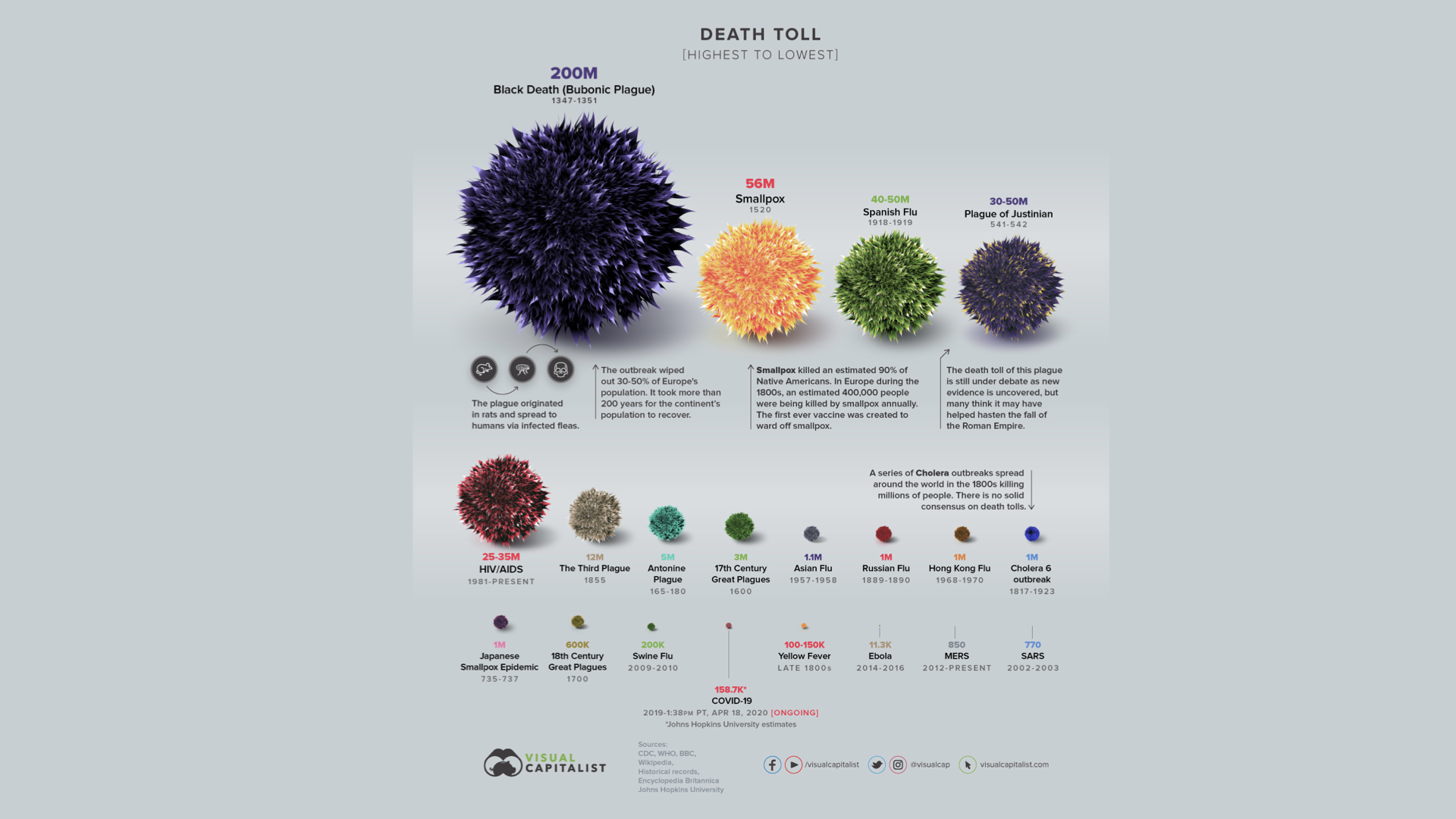

[00:20:11] And strange though it is to say at this time, COVID is actually not one of the worst-case outcomes. The infectiousness of the disease could have been much higher. The fatality rate could have been much higher. To put this in perspective, here is a visualisation of the worst pandemics over time.

Here is where COVID-19 fits in [see the bottom row, fourth dot over from the left]. Obviously, this is just the death toll [as of June 2020]. It will increase a lot over the coming year. But this helps us appreciate how huge the death toll of the worst pandemics have been over time. The Black Death killed something like 50% of the population of Europe. The Spanish Flu killed about as many people as World War I and World War II, had they occurred at the same time.

Now, I think risks from pandemics have, in one sense, gone down a lot over the last few centuries for various reasons. We have the germ theory of disease now. We understand how they work. We have modelling. We have the ability to design vaccines and antiretrovirals. All of these things make us a lot safer.

[00:21:28] But there is another trend that potentially undermines that: developments in synthetic biology — namely, the ability to create novel pathogens. There are evolutionary reasons why the largest possible death toll from a pathogen is capped. If you're a virus, you don't want to kill your host because that stops you from spreading as much. Therefore, viruses have, in general, a tendency to become less virulent over time. Twenty percent of you in the audience, though you might not know it, have herpes. That's a very successful virus and is partially successful by not killing its host.

[00:22:24] And so you'll generally see an anticorrelation between how deadly a virus is and how well it spreads. But, if we're able to create viruses in the lab, that correlation no longer needs to hold true. It'd be perfectly possible, from a theoretical perspective (and increasingly from a practical perspective), to create a virus that has the following three combinations of properties:

- The contagiousness of the common cold

- The lethality of Ebola

- The incubation period of HIV

If you were to create such a virus, or perhaps hundreds of such viruses, you could infect everyone in the world with a virus that's 99% fatal, and we'd only start finding out when people started dying, at which point it would already be too late.

[00:23:11] This is technology that is really just around the corner. We're already able to make pathogens more infectious or more deadly. It's called “gain-of-function research”, and this is one of the most rapid areas of technological progress.

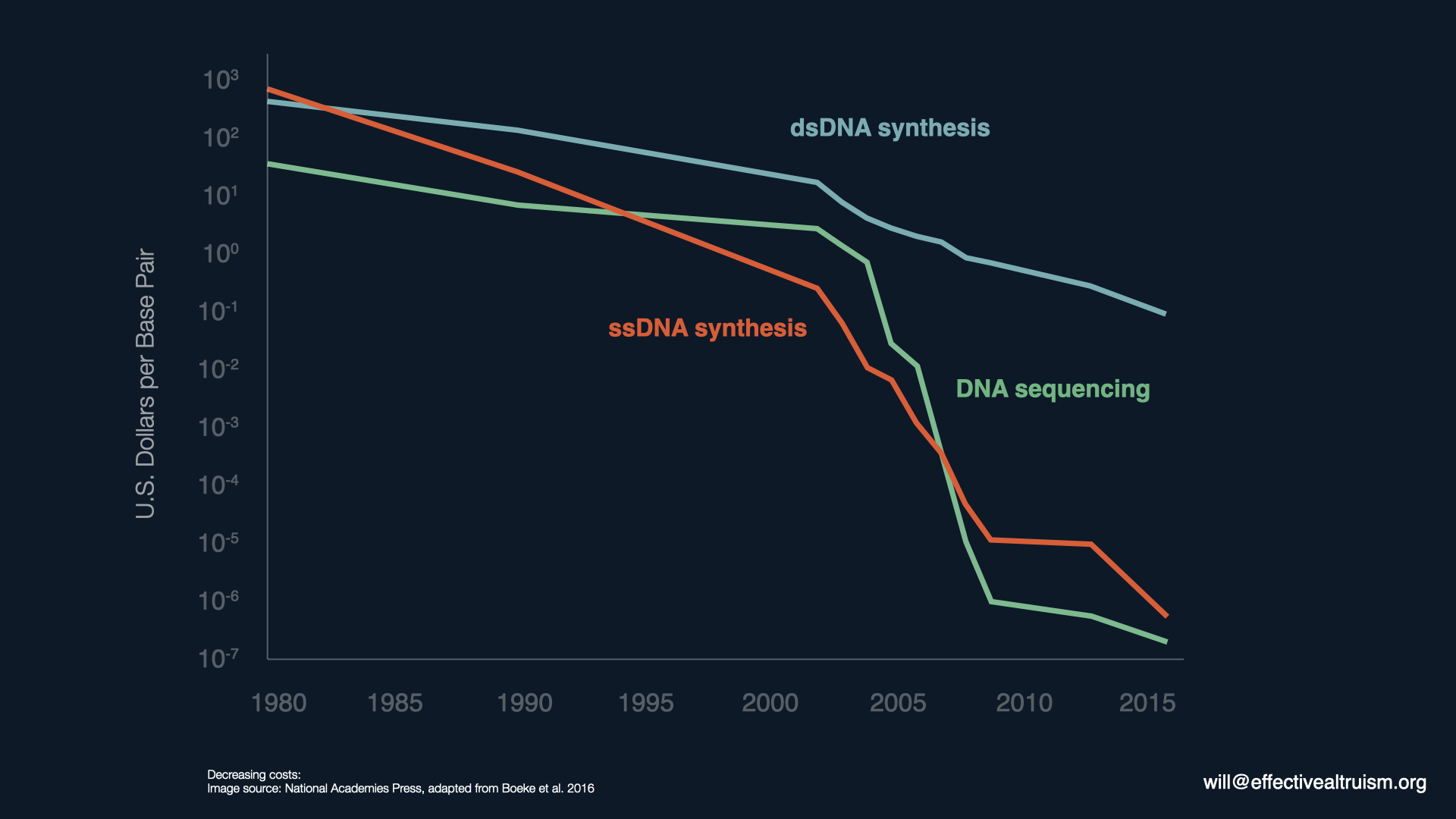

Here is a graph that represents just how cheap it is to do sequencing and synthesis over time. Note that on this side there's a multiple of 10 as we go up, so it's known as a logarithmic scale. If progress were exponential, then it would be a straight line, as double-sided DNA synthesis is, but it's super-exponential. It's actually faster than that. So if you compare it to Moore's law, progress in synthetic biology is considerably faster.

[00:24:06] This creates the possibility of malicious use of such viruses. We've been very thankful to have seen very little in the way of biological warfare. But that could change in the future. Perhaps bio-weapons will be the next generation of weapons of mass destruction.

[00:24:28] Again, I want to emphasise that if you look through history, you do find that civilisation is surprisingly resilient. I actually don't think it's very likely that there will be an event that would cause such a large catastrophe that we would never come back from it. But I also don't think we should be very confident that that wouldn't happen. I don't think it's something we can rule out given the magnitude of the stakes.

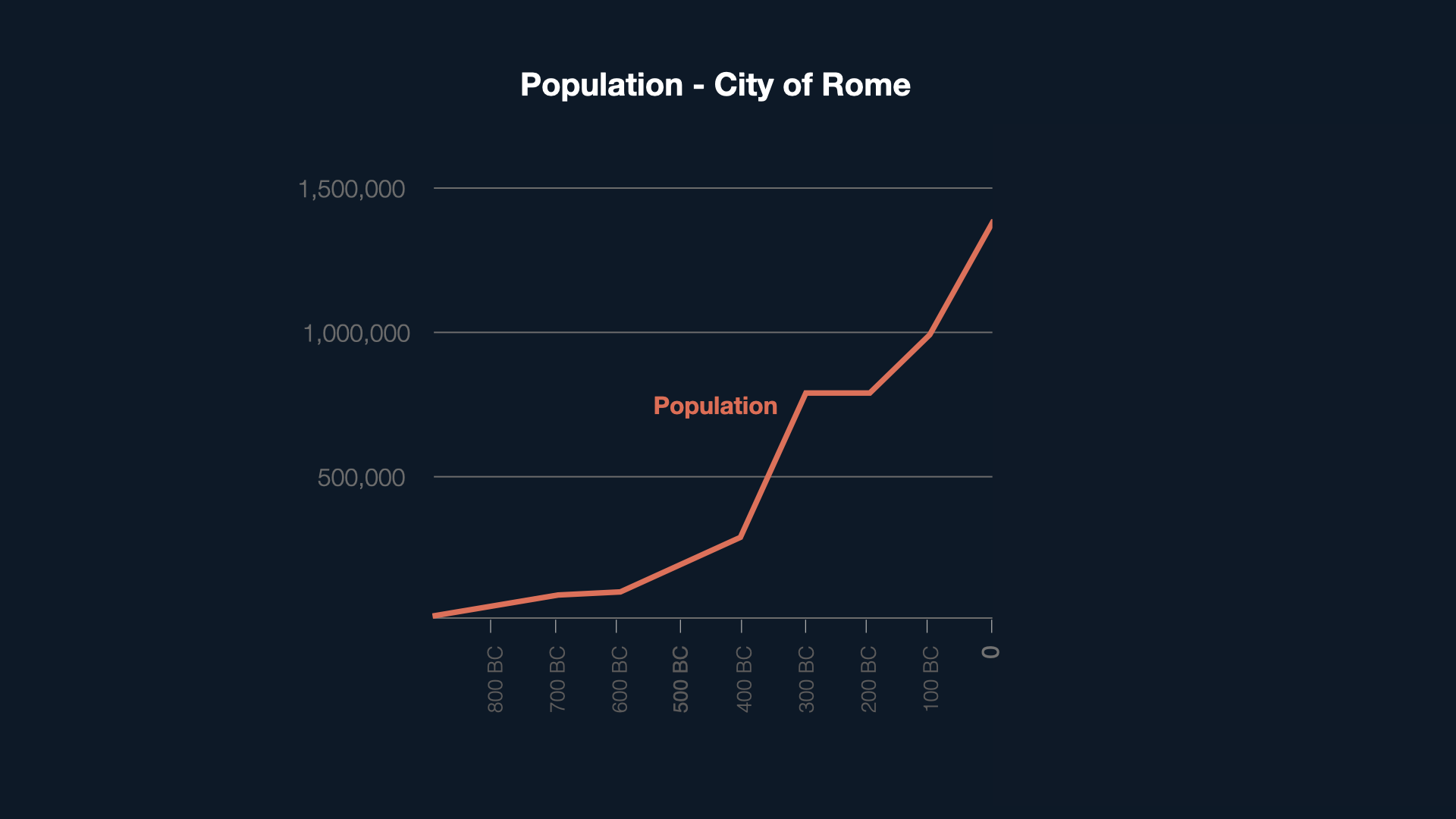

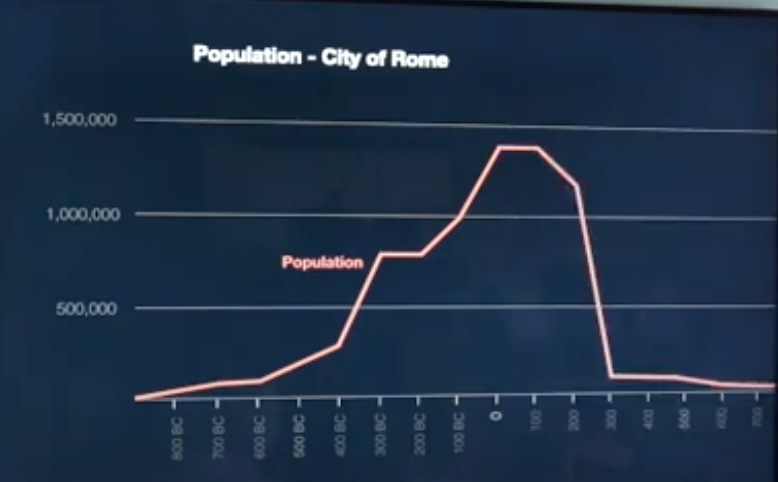

[00:24:57] As an analogy, you might think if you're living in this society, things are going well. The population is booming. We could also put incomes over time in the same graph. They’ve increased a lot. You might think we're on a steady, exponential trend. Things are going to keep getting better and better.

[00:25:17] But this graph represents the population of the city of Rome up until 0AD, which then plateaued and collapsed. It only regained its population at its peak in 1930. There were 1,900 years of collapse.

Values change

[00:25:38] That's the possibility of civilisational collapse. The final category I want to talk about is values change. I think this might be the most important of all. It's one I started learning about only very recently. And the key idea here is that the moral norms that a society holds are very important in terms of how valuable we think society is. If a society owns slaves, we might think it'd be better if that didn't even exist.

What’s crucial is that changes to values seem to be surprisingly persistent over time. Just ask yourself the question “What’s the best-selling book this year?” And the answer is not 50 Shades of Gray. It's not Harry Potter.

It's the Bible, as it is every single year, and by a large margin. And the second best-selling book every year is the Koran. And this is just astonishing. The book that sells the most and potentially has the most influence was written between 1300BC and 100AD. And obviously, the interpretation of the Bible has changed dramatically over time. But it's still evidence that there are certain moral norms that got locked in as a result of Christianity, rather than other religions, becoming so successful. Some of these norms have been so successfully promoted that we might even take them for granted now.

[00:27:25] Consider the idea of infanticide. Almost everyone in the modern world regards the killing of infants as utterly morally opprobrious, just beyond the pale. But at 0AD it was actually quite common practise in Greek and Roman society. It was regarded as just one of those things, part of life, and Christians were quite distinctive insofar as they had a very strong prohibition against infanticide. That became a norm as a result of the spread of Christianity.

[00:28:07] However, we have more than anecdotes, because there's a new and very exciting field of research. The leaders of this field, such as Nathan Nunn, are based at Harvard, and the field is called “persistence studies”. It involves looking at effects that have had a very long influence. And we find, over and over again, examples of moral change in the distant past still having impact even today.

[00:28:33] One example is the adoption of the plough in some countries as a method of agriculture. It turns out that those countries show lower participation from women in the labour force, even today. And why is that? Well, plough agriculture, as compared to the use of the hoe, a digging stick, involves large amounts of upper body strength and bursts of power. So countries that use the plough had a much more unequal division of labour between the genders, and as a result, less egalitarian gender norms.

That cultural trait seems to have persisted into modern times. And there’s not just lower participation of women in the workforce; there’s also lower ownership of firms by women and lower political representation for women. This phenomenon even seems to hold among second-generation immigrants in the US.

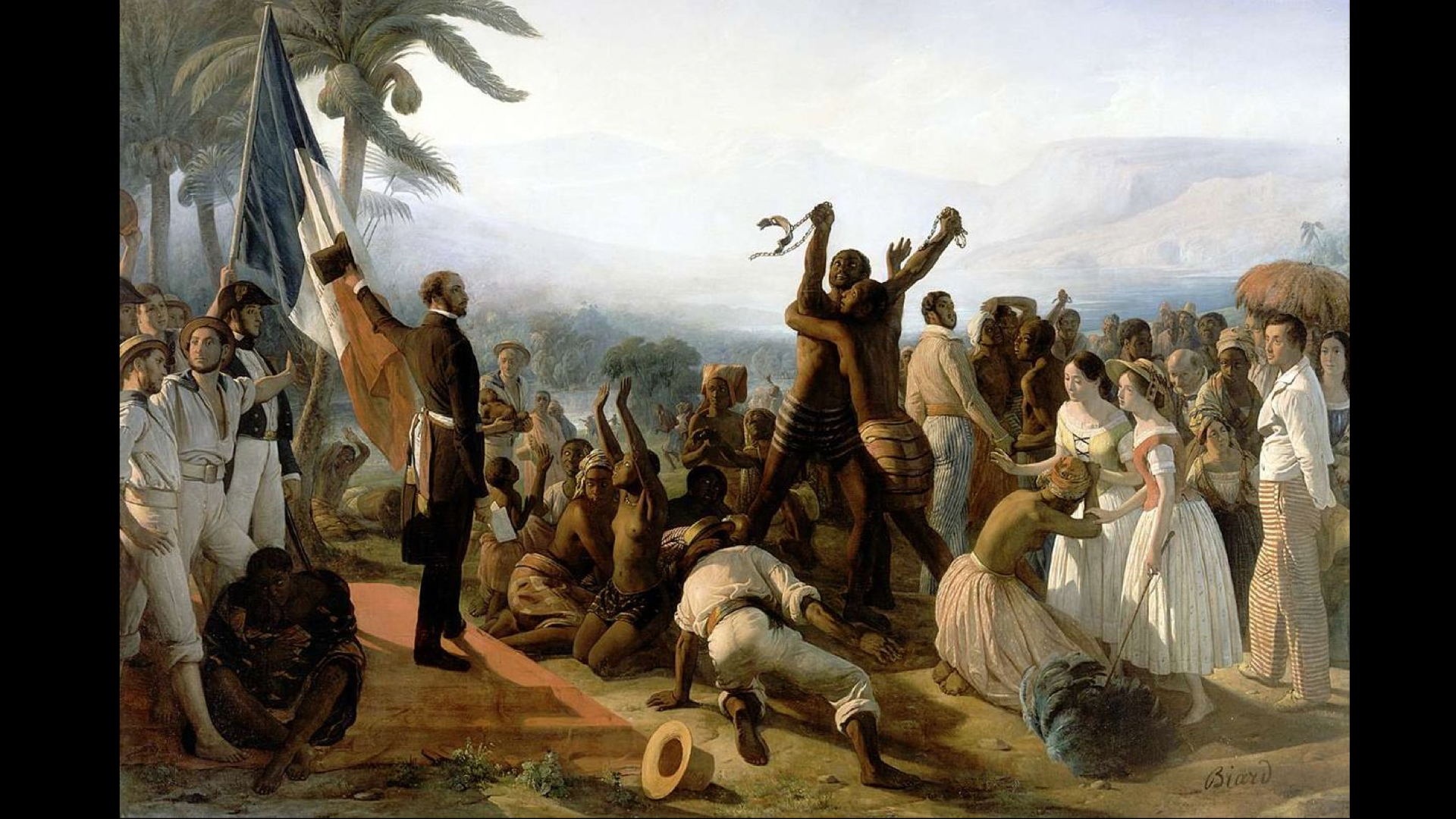

[00:29:41] That's one example, but there are many more, and I'll just mention two. Another is that if you look across countries in Africa, those countries that had a larger proportion of their population taken as slaves in the colonial era show lower levels of social trust and GDP per capita today. They're poorer today, in part because of the slave-trading that occurred during the colonial era.

[00:30:07] A third example is visible in Indian towns that were trading ports in the mediaeval era. There was a strong economic incentive to have a more cosmopolitan outlook. Those towns demonstrate lower levels of conflict between Hindus and Muslims over the 19th and 20th centuries. This religious tolerance, which was developed in those trading towns, is still present.

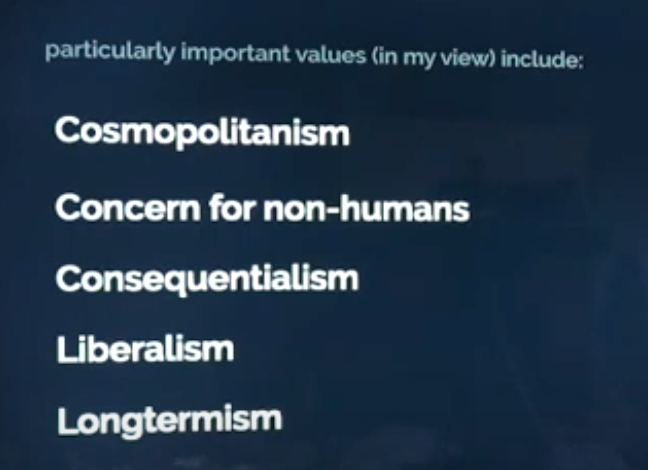

[00:30:36] When we look to the future, I don't think that the world has yet got its values right. Some particularly important values, in my view, include:

- Cosmopolitanism, which is the idea that everyone around the world has the same moral worth. From a global perspective, this is still a very niche perspective.

- Concern for non-human animals. This is another example where there are norms that we take for granted. We think this is the way it is, and therefore, the way it must be. But in India, a third of the population is vegetarian. Perhaps if Hinduism had become a more dominant religion and if India had had an industrial revolution, we would have much greater concern for non-humans than we have today. Perhaps factory farming, as we currently practise it, would not exist.

- Consequentialism. Most people around the world still think of morality in terms of following rules rather than the outcomes that we're trying to achieve. Liberalism is obviously much more widespread, but certainly not destined to continue into the future. It’s particularly important, if we have this long-term perspective, to be able to course-correct and engage in experiments in living. We need to figure out what the right way to live is, and to hopefully converge on morally better ways of structuring society.

- Longtermism itself. This is a realisation that has only come about in the last few years or decades. It’s a value that is not widely held at all.

[00:32:27] The gap between where we might like society's values to be and where they currently are is very great. And we have evidence that values persist for many centuries, even thousands of years, and that they could be even more persistent into the future.

[00:32:48] The analogy here is between cultural evolution and biological evolution. For 600 million years we had a wide diversity of species of land animals roaming the planet, with none particularly having more power than another — certainly, none being completely dominant. But then one species, Homo sapiens, arose and became the dominant species on the planet. And that resulted in a certain amount of lock-in; it means the future of civilisation is driven by Homo sapiens rather than bonobos that developed high intelligence, or chimpanzees that developed high intelligence.

[00:33:33] In terms of cultural evolution, we're at that stage where there is not yet a dominant culture. There's not yet one culture that's become sufficiently powerful to have taken over the globe. Francis Fukuyama suggested in his article “The End of History?” that it was liberal Western democracy, but I think he called it a little bit too soon. If, over the coming centuries, there is a convergence (for any number of possible reasons) on one particular set of values in the world, and one particular culture, then there becomes very little reason to deviate from that.

What can you do?

[00:34:13] The last thing I'll talk about is what you can do. If you're convinced of these arguments, and if you want to try to use your life to do as much good as you can, and in particular with an eye to the very long-run future, the most important decision you can make is what you do in your career.

Because of that, I set up an organisation called 80,000 Hours, whose purpose is to help you work out which career path is the one where you can have the biggest positive impact, and help you really think through this question. It's called 80,000 Hours because that's the number of hours you typically work over the course of your life. And for most decisions, it seems reasonable to spend 1% of the length of time you spend [on the activity] debating [what the activity should be] (i.e., the question of prioritisation). If you're deciding where to go out for dinner, you might spend five minutes looking up a restaurant. That seems reasonable. Well, applying that same logic to your career choice, if you spent 1% of the time spent on your career deciding how to spend it, that would be 800 hours. But I suspect that most people don't spend quite that length of time.

[00:35:45] I think they should. I think that it's sufficiently important. And so, via a podcast, via in-depth articles on the website, and via the small amount of one-on-one advising that they're able to do, 80,000 Hours is trying to give you the best advice they can in terms of how you can make a positive difference.

[00:36:05] I'll highlight four particular focus areas:

- Global priorities research. That's what I do. It entails researching this question of how we can do the most good. For example, is longtermism true? What are the arguments against it? If it is true, what follows? Which of these areas that I mentioned are most important, and what areas haven't I mentioned or even thought about that are even more important? The Global Priorities Institute is my institute at Oxford. It is interdisciplinary, involving both philosophy and economics. But this sort of research is conducted across the effective altruism community.

- Pandemic preparedness. Obviously, this is particularly important in the present moment, and 80,000 Hours has plans to make this their main focus over the coming year. As I mentioned before, the effective altruism community regarded pandemic preparedness as a top-tier cause for many years, and it is simply the case that if we were better prepared from a policy perspective, and if we had better technology, then we wouldn't be in the mess that we're currently in. And as I say, future pandemics could be even worse. I think the next few years could provide an unusual window of opportunity to make change in this utterly critical area, because what we should be saying after this pandemic is over is “never again”. And that gives us an unusual window of opportunity for leverage.

- Safety and policy around artificial intelligence. I didn't get to talk about this because it really warrants a lecture, or many lectures, of its own. I'll just highlight that it's not just about what you might have heard of — the scenarios like Terminator — although there are people who are concerned about takeover scenarios. There's actually a wide array of reasons why you might think that the very, very rapid progress that we're currently seeing in deep learning could be important from a long-run perspective. It could potentially lead to much faster economic growth, disruption of the existing balance of powers, and use as a vehicle for certain technological weaponry that affects the chance of war. You can also think about it simply in terms of the enormous benefits that we could potentially get from advanced artificial intelligence.

- Movement-building [00:38:50]. The final area I want to highlight is, I think, the most important of all. It relates to values change, as I was discussing before. Movement-building involves trying to increase the number of people who take the ideas of effective altruism and longtermism seriously. This is something that is accessible to you, too. It's something you can get involved with right away. And I believe it's the highest-impact volunteering opportunity that you have. And you can get involved through this organisation [where MacAskill’s talk took place], Harvard Effective Altruism, which is the local group of effective altruism that I think is endorsed by Professor Pinker himself.

[00:39:37] And why is this so high impact? Well, at Harvard, you have possibly the densest concentration of future leaders of anywhere on the planet. And you have access to them; you can influence how they might spend their 80,000 hours of working time. And if you can convince just one person to do as much good as you plan to do over the course of your life, you've done your life's work.

If you convince two other people, and then go on and do good yourself, you've tripled your lifetime impact. That's why promoting these ideas — trying to convince other people to think seriously about how they can do as much good in their life as possible — has enormous potential value.

Thank you again for listening.