ERA's Theory of Change

By nandini, Tilman, MvK🔸 @ 2023-08-10T13:13 (+28)

This post is part of the “Insights of an ERA: Existential Risk Research Talent Development” sequence, outlining lessons learned from running the ERA Fellowship programme in 2023.

Executive Summary

- The ERA Cambridge Fellowship focuses on increasing awareness of existential risk, helping fellows develop critical skills useful to the field, and offering them chances for career exploration and networking. These opportunities come from hands-on research projects, interactive workshops and seminars, and networking events with leading professionals.

- The fellowship's success depends on the fellows' willingness to learn, the relevance of research projects, the effectiveness of practical experience, and the potential for meaningful networking and collaborations.

- In the short term, we aim to improve the fellows' research and communication skills and give them a clearer idea of their career paths.

- Over time, we hope the fellowship will encourage fellows to pursue careers in existential risk, improve the quality of research in the field, and stimulate active collaboration among researchers.

- In addition to knowledge and skill-building, the fellowship also works to instil in fellows a deep respect for truth-seeking and finding a balance in what can be an intense research career.

- We anticipate and respect that while the ERA Fellowship aims to foster a passion for existential risk research, individual career trajectories and alignment will naturally result in only a subset of fellows pursuing it as a primary focus post-fellowship.

- We recognise the potential challenges associated with running ERA, including the risk of fellows dissociating from existential risk research, not developing the necessary skills, not having enough opportunities for networking, not being satisfied with the fellowship, and dropping out. We have strategies in place to mitigate these risks the best we can. So far, we have not seen any evidence of this happening.

- We value and welcome feedback from fellows, researchers, and other stakeholders, and are always looking for ways to improve the programme.

Overview

The ERA Cambridge Fellowship, previously known as the CERI Fellowship, is an eight-week paid programme focusing on existential risk mitigation research projects, from July 2023 to August 2023, and aimed at all aspiring researchers, including undergraduates. More notes on the structure of the fellowship can be found here.

The rest of this post outlines our theory of change, key objectives, underlying assumptions, expected impact and failure conditions. We conclude by listing our key uncertainties, which we will highly appreciate the community’s input on. Note: this post errs more towards being qualitative, and tries to make our TOC transparent. Behind the scenes, we have a more rigorous set of OKRs that we are using to track our impact, and we will share further details on that in our impact eval post.

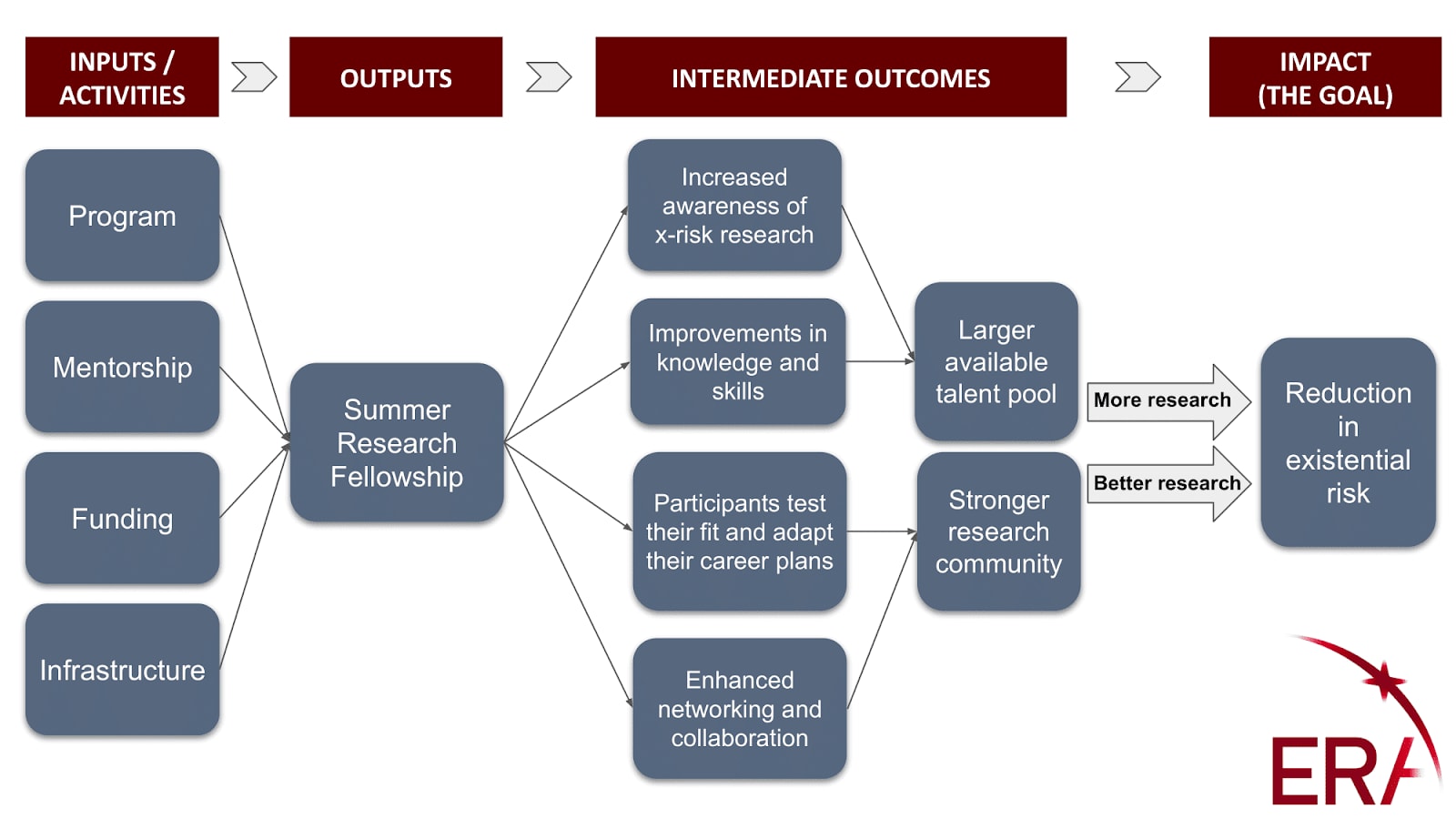

Our Theory of Change

The ERA Fellowship aims to grow the number of dedicated researchers focused on mitigating existential risks by providing training, mentorship, and community support for early-career researchers. Our theory of change posits that by recruiting promising candidates, enhancing their skills and knowledge, connecting them to a community of experts, and supporting them as they explore research roles, we can counterfactually impact their career trajectories and motivate more people to pursue and persist in existential risk research.

Crucially, we here at ERA believe that we will not have succeeded if we simply supply training and infrastructure to upskill researchers. Rather, we are convinced that in order to provide sustainable field-building value to a fast-paced and novel area of research, it is imperative to create a space where Fellows get to exercise autonomy and agency to develop their own research ideas, encounter their opportunities and limitations and constantly learn throughout this process. ERA’s vision - which is reflected in this Theory of Change - is to support future change makers who are motivated and capable to construct new research agendas, pursue impactful projects and lead the discourse rather than simply following it.

Strategic Planning

The primary objective of ERA is to contribute to the reduction of existential risks by cultivating a larger, more robust pool of talent within the research community. This feeds directly into our key objectives for the fellowship, which also inform our prioritisation for programme activities.

The key objectives of the Fellowship are:

- Enhancing awareness and understanding of existential risk among the fellows. This serves to expand the field and create more informed researchers and potential policymakers.

- Elevating the knowledge, skills, and competencies of the fellows in areas pertinent to existential risk research, ensuring they have the tools necessary to contribute meaningful and impactful work to the field.

- Providing fellows with the opportunity to test their fit for careers in existential risk research or mitigation, thus increasing the likelihood of long-term dedication and contribution to existential risk mitigation.

- Fostering strong connections between fellows and other researchers for future collaboration, thereby creating a vibrant network of dedicated professionals in x-risk research.

To achieve these objectives, ERA engages in the following strategic activities:

- Research Projects: As the cornerstone of the fellowship, participants are given opportunities to work on specific existential risk research projects. This hands-on experience is expected to provide them with valuable insights into what a career in this field would entail. The process starts with the fellows proposing a research topic, then working with a Research Manager to develop a proposal, and finally creating an actionable plan with a suitable research mentor. By creating a space for our fellows to conduct their own research, we enhance their understanding of existential risk (Objective 1) and help them develop the necessary skills and competencies (Objective 2). Throughout this process, fellows enjoy a large degree of autonomy, setting them up to conduct a project with minimal oversight, while still providing a sufficient safety net and ongoing support where it’s needed.

- Workshops and Seminars: Our structured workshops and seminars aim to increase the fellows’ awareness and understanding of the nuances of existential risk. Topics range from x-risk-specific aspects, like the “History and Ethics of x-risk,” “Governance in x-risk,” and “Approaches to Existential Risk Studies” to additional events tailored to the interests of the fellows, as organised by our Research Managers. This covers socials with relevant figures and talks from researchers. We also offer workshops focused on self-care, work-life balance, and career development. These include sessions on topics like time management, avoiding burnout, and mapping long-term career trajectories. Our goal is to support our fellows not just in their technical work, but in developing sustainable, fulfilling careers. By deepening their knowledge base, we again contribute to Objective 1, as well as providing opportunities for skill and competency development (Objective 2).

- Skill-enhancement sessions: These dedicated sessions focus on developing both general research capabilities and those specific to existential risk research. Workshops in this category include “How to Create a Theory of Change”, “Workshop on Writing”, and “Forecasting”. Equipping fellows with these skills bolsters their ability to contribute effectively to the field (Objective 2).

- Networking Events and Group Projects: We both organise networking events and support group projects to help foster connections between the fellows and the broader research community. These interactions encourage future collaborations and ensure the fellows remain involved in existential risk research even after their fellowship ends. Planned events are with relevant research orgs in London, Kruegers Lab, CSER and others! By doing so, we encourage future collaborations (Objective 4) and give fellows a clearer idea of their fit within the existential risk research community (Objective 3).

- Reading Groups: We have both organised and facilitated the fellows organising or participating in reading and discussion groups, to allow fellows to more deeply learn and develop ideas in relation to XRisk as a field. This contributes to Objectives 1 and 2, and in the cases of some reading groups with participants from outside ERA, Objective 3 as well.

By linking our activities to the programme's objectives in this way, we hope to provide a clearer picture of how the ERA Fellowship plans to achieve its goal of increasing the pool of dedicated existential risk researchers.

Assumptions and Evidence

The following analysis tracks the different steps of our Theory of Change and examines each link, outlining our respective confidence in each assumption. Notably, one crucial link is excluded from the following section: The assumption that more & better[1] research leads to the reduction of existential risk. We have decided to acknowledge that the strength of this link could be contested, but that opening the debate around the tractability of x-risk research is beyond the scope of this post. For interested readers, we recommend the following ressources: Democratising Risk, How tractable is changing the course of history, How much does new research inform us about existential climate risk?, How tractable are global catastrophic risks? and The Epistemic Challenge to Longtermism.

Assumptions of our Activities and Interventions include:

- There is a demand for this kind of Fellowship: If our programme does not serve an unmet need, resolves a key bottleneck or fails to attract the kind of candidates we are looking for, it would not be the most effective use of our resources. Confidence: High - Conversations with funders and organisers of other programmes lead us to believe that the space is still largely talent-constraint, and that ERA fills an important gap in providing opportunities for junior researchers. We have also confirmed our assumption about our ability to attract suitable talent in our most recent hiring round, which attracted >600 applicants.

- ERA possesses the necessary resources to plan, run and evaluate this Fellowship: Ressources here include funding, infrastructure and human resources. Connecting this to assumption #1, it becomes obvious that a demand needs to be met by an adequate supply, and our eventual success relies on our ability to provide the necessary structures for the Fellowship to succeed. Confidence: High - ERA has previously successfully raised money for its programs and is now running the 3rd iteration of this Fellowship. Thanks to our cooperation with the University of Cambridge and close ties with EA Cambridge, structures have been put into place to provide a nurturing environment for Fellows, including access to a co-working office, accommodation etc. We were able to attract suitable talent to lead ERA’s efforts on operations, community management, research management, and executive leadership.

- Fellows are receptive to learning: The effectiveness of workshops, seminars, and skills-enhancement sessions is predicated on the assumption that the fellows are not only eager and open to learning about existential risk and related research methodologies, but they actively engage in the process. Confidence: High - We infer from our pre-Fellowship survey that at least 81% of the fellows made learning to research or improving knowledge in their respective cause area one of their top priorities for the Fellowship. We also feel that our application process both intentionally and indirectly selects for traits such as “openness to new ideas” and “quick learner,” which further increases our confidence in this assumption. [2]

- Existential risk projects are suitable for fellows: We assume that projects are appropriate for the fellows' skills and interests. These projects should provide an accurate representation of the field of existential risk research. Confidence: Medium - While we try to help fellows with their research proposals in making SMART goals, ultimately, the research mentor has more leverage on giving feedback on the research and thus effectively steering the direction. However, we arrange mentors for each fellow based on personal fit to try our best to safeguard against this failure mode.

- Hands-on experience can help career assessment: There is an underlying assumption that allowing the fellows to work on existential risk research projects will allow them to evaluate their fit and interest in a career in this field. Confidence: Medium - In the post-Fellowship survey last year, fellows ranked “testing fit” as one of the highest-valued parts of the fellowship. There is also an extensive body of literature from adjacent fields that supports this assumption (Schnoes et al. 2018, Inceoglu et al. 2019, Krauss/Orth 2021, Rothman/Sisman 2016). [3]

- Networking leads to collaboration: Our strategic plan assumes that by fostering connections between the fellows and the broader research community, these relationships will translate into future collaborations. Confidence: High - According to responses from the post-Fellowship survey, participants overwhelmingly indicated that the highest value derived from their fellowship was the opportunity for networking. This is corroborated by the majority of scientific inquiry into this subject (see e.g. Vermont et al. 2022, Kyvik/Reymert 2017, Burt/Kildoff/Tasselli 2013, Ansmann et al. 2014), some of which highlights the outsized importance of networking particularly for early-career researchers, which is our main target group for the fellowship.

- Researchers and policymakers are willing to engage with fellows: The success of the networking events is dependent on the willingness of established researchers and policymakers to interact with and mentor the fellows. Confidence: Medium - Since it was the most valued part in the last year, we assume at least some of the established professionals engaged meaningfully with the fellows. Our ability to source a variety of speakers from across academia, industry, think tanks, and the government is further evidence to support this assumption.

- Fellows will stay engaged in existential risk research after the fellowship: One of the fundamental assumptions of the fellowship is that the experience will inspire the Fellows to continue contributing to existential risk research even after the fellowship ends. Confidence: Low [4]- Since part of the motivation for some fellows is to “test fit” in this career, we assume that some fellows will decide not to pursue x-risk research after the programme. Looking back at previous iterations of this fellowship, most of the alumni are still pursuing degrees. We assume, based on some personal contact and rough googling, that roughly 80% are still doing x-risk relevant work (research, community- or field-building), whereas roughly 60% do direct research. Our goal is to collect more data on this over time, as previous alumni of the programme start jobs and mature into positions of increasing seniority. A forthcoming post on some alumni stories will be a first step in this direction.

Each of these assumptions plays a significant role in the overall effectiveness of the strategic plan for the ERA Cambridge Fellowship. Monitoring the validity of these assumptions as the fellowship progresses can help us make any necessary adjustments to the strategy.

Expected Results and Impact

This section anticipates the outcomes of the ERA Fellowship, considering both immediate and long-term impacts, and how these contribute to broader goals within the field of existential risk.

Short-Term Outcomes

- Research Skills Development: In the short term, fellows will acquire and hone their research skills. They will learn to understand the nuances of existential risk research, including the methodologies and approaches typically used in the field.

- Effectively Communicating Research: We are committed to ensuring our fellows not just produce quality research, but also communicate it effectively. We place emphasis on presentation skills, guiding fellows on how to articulate their findings across diverse platforms - be it internal documents, forum posts, or potentially, published academic papers, and at our research symposium.

- Career Clarity: By the end of the fellowship, participants should have a clearer idea of their future career paths. The hands-on experience and exposure to the field will allow fellows to evaluate their interest and aptitude for careers in existential risk research and mitigation.

Long-Term Outcomes

- Pursuit of x-risk Relevant Careers: In the long term, we expect that many of our fellows will pursue careers that are relevant to existential risk. This could include research, policy development, or risk mitigation strategy roles. The fellowship will provide valuable data points for the fellows to consider in their career decisions.

- Improved Research and Collaboration: For those who pursue a research career, we anticipate they will produce higher quality research as a result of their participation in the ERA Fellowship. We also expect that they will actively collaborate with others in the field (including, but not limited to, ERA alumni, mentors, etc.) to work on existential risk mitigation, and we’re currently working on establishing a stronger and more collaboration-encouraging alumni community.

While these are the expected outcomes, the dynamic nature of research, careers, and the existential risk field might lead to different results. It is not uncommon for fellows to step off conventional paths, carving out distinct roles that align their personal growth with the shifting needs of the field.

An important part of the ERA Fellowship is our commitment to nurturing an environment that encourages epistemic virtues. We seek to foster more than competent researchers and critical thinkers; our goal is to imbue our fellows with an enduring respect for truth-seeking, the ability to appreciate nuanced perspectives, and a mindset of intellectual humility. We believe that navigating the complex field of existential risk is less about rigidly following a predetermined plan, and more about engaging deeply with the intricacies and nuances of the field.

One of the ways we have tried to achieve this is by exposing fellows to views from those across the existential risk field. This has been done chiefly through the programming, with talks and workshops given by people from a wide variety of perspectives, and through the reading groups, which have also exposed fellows to a diverse range of viewpoints. To set a mentality of this, we spent the first two days of the fellowship with a variety of talks and workshops that explored very different views of x-risk, to hope to set a norm that alternative ways of viewing the problem were encouraged. We also explicitly ask them to set goals (both long-term and short-term), and employ robust feedback mechanisms within the fellowship itself to create a culture of openness.

Failure Conditions

In this section, we examine potential conditions that would indicate failure and provide an assessment of our certainty in detecting these conditions, given the evidence and mechanisms at our disposal.

Failure Condition | Explanation | Mitigation Strategy | Key Factors | Risk Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dissociation from Existential Risk Research Post-Fellowship (this is more of a downstream result of earlier failure conditions, but felt worth mentioning) | This relates to fellows actively moving away from x-risk research post-Fellowship due to a negative perception of x-risk research because of the programme itself. | Regular follow-ups with fellows post-programme to continue the discourse, offering resources, encouraging participation in research projects or discussions in the field. | Individual career trajectories, job market conditions and shifts in the funding landscape, personal circumstances, and shifting interests, counterfactual opportunities. | Moderate |

| Inadequate Development of Crucial Skills | If the fellowship does not significantly improve crucial skills such as research methodology, critical thinking, reasoning transparency, etc., it could indicate shortcomings in our programming and present a bottleneck to our fellows’ future impact. | Implementing a rigorous and continuous assessment and feedback system for skill development. Regular reviews of the workshops to keep them relevant and effective. Employing best practices in skill development, i.e. project-based learning, spaced repetition etc. | Quality and quantity of educational modules, effectiveness of mentors, fellows' pre-existing skill levels and learning capacity, ability to secure leaders for workshops. | Low |

| Limited Networking and Collaborative Opportunities | If the fellows do not form substantial collaborative relationships or a robust network during the programme, it could reflect a deficiency in our networking facilitation or social events. This is of particular concern for remote fellows. | Organising more engaging networking events, fostering a collaborative culture through team projects, promoting active participation in academic discussions and community engagement. | Individual networking skills, time constraints, availability of opportunities, fellows' willingness to participate, other logistical and financial constraints. | Moderate |

| Fellowship Satisfaction Below Expectations | This refers to if satisfaction scores fall below our set standard, suggesting a mismatch between the fellows' expectations and the programme's delivery. [There is an opposite failure mode of “goodharting” for better survey scores.] | Regular surveys to gauge satisfaction, fostering an open dialogue for feedback, implementing improvements based on feedback. Get additional input from other Fellowship organisers on best practices (SERI MATS, CHERI, etc.). | Quality of programme execution, alignment with fellows' expectations, effectiveness of feedback mechanism. | Low |

| Sparse Research Outputs | If fellows do not produce relevant and impactful outputs, this could indicate gaps in our research guidance or a lack of resources dedicated to supporting them in this regard. | Additional resources and guidance for research and publication opportunities, facilitating collaborations with established researchers, time management training, clear expectation management. | Individual research capabilities, availability of resources, time constraints, complexity of research topics, ToC of a given fellow’s project, infohazards. | Moderate |

By associating a tentative risk level with each potential failure condition, we aim to honestly represent our current understanding and acknowledge the inherent uncertainties involved in deciding when to pivot our strategy considerably.

Key Uncertainties

As part of our mission to cultivate a robust, collaborative environment within the existential risk research community, we invite you to think about and potentially address several open questions and uncertainties we are considering internally. Your perspectives and insights on these topics are invaluable and could substantially impact the trajectory of the ERA Fellowship and the wider field:

- Understanding Impact:

- What are the best indicators of success for an initiative like the ERA Fellowship?

- Are we sufficiently capturing the true impact through our current metrics and evaluation methods, or are there other less tangible, yet meaningful measures we should consider?

- Balancing Breadth and Depth:

- How do we strike the right balance between offering a broad overview of existential risk topics versus providing in-depth, specialised training?

- Should the fellowship be tailored more towards generalist or specialist training?

- What sorts of specialist training is even appropriate in the x-risk context?

- Mentorship and Networking:

- How can we ensure that the mentorship and networking opportunities provided are of the highest quality and most beneficial for the fellows?

- Are there novel approaches or methods that could enhance these aspects of the fellowship?

- Long-Term Engagement:

- What are the most effective ways to maintain engagement with fellowship alumni and ensure their continued involvement in existential risk research post-fellowship?

- Outcome Interpretation Dilemma:

- How can we effectively measure and interpret the outcomes of the fellowship when both paths (pursuing x-risk research or choosing alternative impactful areas) are perceived as successes?

- This raises the challenge of assessing the true value and impact of our programme. Is there a reliable way to differentiate between genuine success and simply rationalising all positive outcomes?

The ERA Fellowship is just one part of a wider ecosystem. We see immense value in collaboration and open discussion, and thus we invite our fellows, researchers, and other stakeholders to bring their perspectives to the table. This dialogue helps us refine our approach, enhance our programme, and, ultimately, contribute more effectively to building the existential risk research community.

Please feel free to either leave a comment here or email us at nandini@erafellowship.org. You can also contact us via our anonymous feedback form.

Credits

This post was written by Nandini Shiralkar, Tilman Räuker, and Moritz von Knebel, part of the ERA team, a fiscally sponsored project of Rethink Priorities. We are especially grateful to Michael Aird and others who kindly shared their insights and provided constructive feedback on this post or related documents. However, it's important to note that their feedback doesn't imply complete endorsement of every viewpoint expressed in this post. Any inaccuracies, errors, or omissions are solely our responsibility. We encourage readers to engage critically with the content and look forward to incorporating further feedback as we continue to refine our understanding and approach.

- ^

A discussion on this topic would necessarily require some explanation and operationalisation as to what “better” research entails and how this could be monitored and evaluated, but we consider such a discussion to be out of scope for this post.

- ^

The remaining 19% either gave no answer or focused on more networking within the Fellowship.

- ^

There is also some evidence that suggests the link is overall not as strong as we claim: Callanan/Benzing (2004) find “that the completion of an internship assignment was linked with finding career-oriented employment, but was not related to a higher level of confidence over personal fit with the position that was selected.” However, the external validity of this particular study might be limited.

- ^

“Low” here is pointing more towards a “lack of evidence” rather than fundamental doubts about the assumption itself.

Moneer @ 2025-01-26T12:11 (+1)

I'd rank this article amongst top 10% of the +20 Theories of Change that I've co-developed/evaluated as an impact consultant.

Key Strengths:

-coherent change logic [output-->outcomes (short/med)-->impact]

-depth of thought on:

*assumptions (with evidence, cited literature, reasoning transparency)

*anticipated failure modes (including mitigation strategies and risk level)

*key uncertainties (on program, organisational, and field level)

Potential Considerations:

-Think about breaking down ERA's theory of change by stakeholder group, to expand your impact net. Stakeholder group examples: (Fellows) (Mentors) (ERA Staff) (Partners: Uni of Cambridge? Volunteers?). And then ask what are potential outcomes of ERA's activities for each group over time. The current ToC seems to focus mainly on Fellow-related outcomes. What about other groups? Although many Fellow-related outcomes may apply to other stakeholder groups, there may be other outcomes particular to a stakeholder group that is not yet fully understood/measured/improved upon. Speculative examples:

Outcomes

(ERA Staff) -->. Build program management and operations expertise

-->. Create sustainable/effective talent development models for AIS field

(Mentors) -->. Develop teaching and mentorship skills

-->. Gain recognition as field leaders

(Uni of Cam). --> Access talent pipeline for future researchers/students

. -->. Strengthen position as leader in emergin field

-Think about 'mechanisms' of change, which seeks to identify what about your activities 'cause' your intended outcomes? In other words, what about your outcomes would not occur if activities did not have qualities a, b ,c, etc. A fellowship doesn't just automatically lead to intended outcomes, right? So what about the location, timing, duration, content, messaging, format, application process, mentor matching process, alumni relations process, etc etc etc makes it more likely to produce intended outcomes? I've observed that organisations are better positioned to start thinking more intentionally about mechanisms once they've already developed a robust ToC and have some outcome evidence to support existing assumptions - which I think is where ERA are.

-For the benefit of the winder community (e.g. new fellowships in the making), it could be helpful to see your impact evaluation framework (bits and parts of which can already be assumed from your above blog), maybe even sharing specific indicators and tools used to gather evidence across outcomes.

-Your 'Key Uncertainties' section proposes such critical questions! I don't see comments from the wider community. I'm unsure if you've received individual emails/anonymous feedback. Perhaps a shared document would spark collaboration, and offer the community a live glimpse at how you (or others) are attempting to answer these questions?