The Lightcone solution to the transmitter room problem

By OGTutzauer🔸, MatthiasE @ 2025-01-29T10:03 (+8)

Introduction

At the GCP Workshop last weekend, we discussed what’s known as the “Transmitter Room Problem.” The transmitter room problem is a thought experiment developed by Scanlon:

“Suppose that Jones has suffered an accident in the transmitter room of a television station. Electrical equipment has fallen on his arm, and we cannot rescue him without turning off the transmitter for fifteen minutes. A World Cup match is in progress, watched by many people, and it will not be over for an hour. Jones’s injury will not get any worse if we wait, but his hand has been mashed and he is receiving extremely painful electrical shocks.”[1]

To make the argument stronger we extend the example to a hypothetical “Galactic Cup” where the number of potential viewers is arbitrarily large. Moreover, we assume Jones to suffer as much pain as a human can survive, to consider the most extreme case of the example.

If this individual is spared, the broadcast must be stopped, causing countless viewers across the galaxy to miss the event and feel upset. The question is whether, at some unimaginably large scale, the aggregated minor distress of countless viewers could outweigh one person’s extreme, concentrated suffering.

This dilemma is deeply counterintuitive. Below are two different approaches we’ve seen proposed elsewhere, and one which we found during our discussion that we'd like thoughts on.

1. Biting the Bullet

In an episode (at 01:47:17) of the 80,000 Hours Podcast, Robert Wiblin discusses this problem and argues that the suffering of the individual might be permissible when weighed against the aggregate suffering of an immense number of viewers. He suggests that the counterintuitive nature of this conclusion arises from our difficulty in intuitively grasping large numbers. Wiblin further points out that we already accept analogous harms in real-world scenarios, such as deaths during stadium construction or environmental costs from travel to large-scale events. In this view, the aggregate utility of the broadcast outweighs the extreme disutility experienced by the individual.

2. Infinite Disutility

Another perspective posits that extreme suffering of a single person can generate infinite disutility.[2] For instance, the pain of a single individual experiencing every painful nerve firing at once can be modeled as negative infinity in utility terms. Under this framework, no finite aggregation of utilities induced by mild discomfort among viewers could counterbalance the individual’s suffering. While this approach sidesteps the problem of large numbers, it introduces a new challenge: it implies that two individuals undergoing such extreme suffering are no worse off than one, as both scenarios involve the same negative infinity in utility. It might also be prudent to "save" the concept of negative utility for the true worst case scenarios.

3. The Light Cone Solution

This approach begins by assuming that the observable universe (“our light cone”) is finite with certainty.[3] Even the Galactic Cup cannot reach an infinite audience due to constraints such as the finite lifespan of the universe and the expansion of space, which limits the number of sentient beings within our causal reach. Given these boundaries, the number of potential viewers is finite, albeit astronomically large.

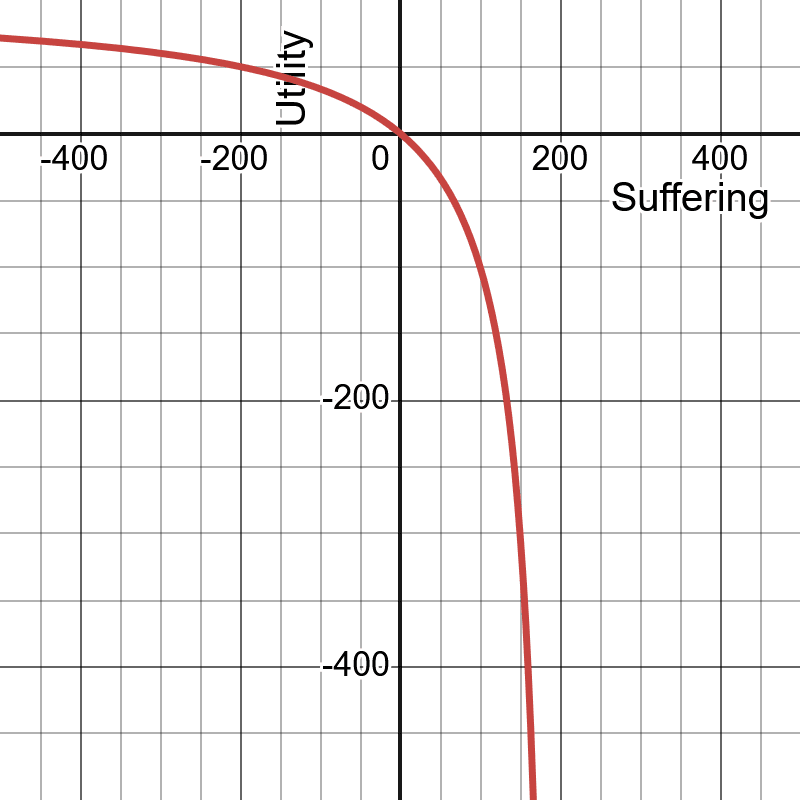

By assigning sufficient negative (but now finite) utility to the individual’s extreme suffering, this perspective ensures that it outweighs the aggregate discomfort of any audience whose size remains within physical limits. This approach avoids saying that multiple people in extreme suffering would be no worse than an individual under such conditions, since sufficiently large but finite negative utility of one individual can trump the mild discomfort of the largest physically possible audience. As the negative utility of this individual is finite, multiple individuals under the same conditions would be worse than one.

Considering that the observable universe being finite only solves the problem for the specific transmitter room problem, one can imagine a variation in which this broadcast doesn’t only affect people watching at the given moment. For the Light Cone Solution to hold, one must then give some reason why time is also finite, or why sentient beings can’t reach infinite numbers given infinite time. This calls into relevance the question of whether Heat Death is real, or other hypotheses for the universe becoming uninhabitable.

To sum up, assuming that the total number of sentient beings will be finite, both in time and space, and assuming that utility is sufficiently concave in suffering might lead to interesting conclusions relevant for EA. Regarding near-termist EA, the insight how the weighting of the intensity of suffering matters for cost-effectiveness analysis has probably been discussed elsewhere in detail. Regarding long-termism, the conclusion seems to be that one ought to prioritize existence and value of the long term future compared to avoiding suffering of small or medium intensity, but it is at least possible that there is a moral imperative to focus on avoiding large suffering today as compared to making the future happen. Alternatively, the proposed way out of the transmitter room problem made me find S-risks more relevant as compared to x-risks.

Open questions

We’d be interested to hear if this solution to the transmitter room problem has been discussed somewhere else, and would be thankful for reading tips Furthermore, we’re curious to hear others’ thoughts on these approaches or alternative solutions to the Transmitter Room Problem. Are there other perspectives we’ve overlooked? How should we weigh extreme suffering against dispersed mild discomfort at astronomical scales?

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Jian Xin Lim for loads of great comments and insight.

- ^

Scanlon, T.M. (1998). What We Owe to Each Other. Belknap Press.

- ^

To fix ideas, consider we analyse how bad a possible world by a (possibly weighted) sum of utilities. Then utilities are the measure how relevant suffering of an individual is for overall welfare. I assume one could weaken a number of assumptions and the argument might still work, but this would go beyond the scope of this post.

- ^

Dustin Crummett @ 2025-01-29T23:37 (+3)

I accept the bullet biting response. I think someone who doesn't should say the utility of the observers may outweigh Jones' utility but that you should save Jones for some deontic reason (which is what Scanlon says), or maybe that many small bits of utility spread across people don't sum in a straightforward way, and so can't add up to outweigh Jones' suffering (I think this is incorrect, but that something like it is probably what's actually driving the intuition). I think the infinite disutility response is wrong, but that someone who accepts it should probably adopt some view in infinite ethics according to which two people suffering infinite disutility is worse than one--adopting some such view may be needed to avoid other problems anyway.

The solution you propose is interesting, but I don't think I find it plausible:

1. If Jones' disutility is finite, presumably there is some sufficiently large number of spectators, X, such that their aggregate utility would outweigh his disutility. Why think that, in fact, the physically possible number of observers is lower than X?

2. Suppose Jones isn't suffering the worst torment possible, but merely "extremely painful" shocks, as in Scanlon's example. So the number of observers needed to outweigh his suffering is not X, but the lower number Y. I suppose the intuitive answer is still that you should save him. But why think the physically possible number of observers is below Y?

3. Even if, in fact, the physically possible number of observers is lower than X, presumably the fundamental moral rules should work across possible worlds. And anyway, that seems to be baked into the thought experiment, as there is in fact no Galactic Cup. But even if the physically possible number of observers is in fact lower than X, it could be higher than X in another possible world.

4. Even if the possible number of observers is in fact finite, presumably there are possible worlds with an infinite number of possible observers (the laws of physics are very different, or time is infinite into the future, or there are disembodied ghosts watching, etc.). If we think the solution should work across possible worlds, the fact that there can only be a finite number of observers in our world is then irrelevant.

5. You assume our lightcone is finite "with certainty." I assume this is because of the expected utility concern if there is some chance that it turns out not to be finite. But I think you shouldn't have epistemic certainty that there can only be a finite number of observers.

6. The solution seems to get the intuitive answer for a counterintuitive reason. People find letting Jones get shocked in the transmitter case counterintuitive because they think there is something off about weighing one really bad harm against all these really small benefits, not because of anything having to do with whether there can only be a finite number of observers, and especially not because of anything having that could depend on the specific number of possible observers. Once we grant that the reason for the intuition is off, I'm not sure why we should trust the intuition itself.

*I think your answer to 1-3 may be that there is no set-in-stone number of observers needed to outweigh Jones' suffering: we just pick some arbitrarily large amount and assign it to Jones, such that it's higher than the total utility possessed by however many observers there might happen to be. I am a realist about utility in such a way that we can't do this. But anyway, here is a potential argument against this:

Forget about what number we arbitrarily assign to represent Jones' suffering. Two people each suffering very slightly less than Jones is worse than Jones' suffering. Four people each suffering very slightly worse than them is worse than their suffering. Etc. If we keep going, we will reach some number of people undergoing some trivial amount of suffering which, intuitively, can be outweighed by enough people watching the Galactic Cup--call that number of observers Z. The suffering of those trivially suffering people is worse than the suffering of Jones, by transitivity. So the enjoyment of Z observers outweighs the suffering of Jones, by transitivity. And there is no reason to think the actual number of possible observers is smaller than Z.

Jim Buhler @ 2025-01-29T14:29 (+3)

Mogensen and Wiblin discuss this problem in this podcast episode, fwiw. That's all I know, sorry.

Btw, if you really endorse your solution (and ignore potential aliens colonizing our corner of the universe someday, maybe), I think you should find deeply problematic GCP's take (and the take of most people on this Forum) on the value of reducing X-risks. Do you agree or do you believe the future of our light cone with humanity around doing things will not contain any suffering (or anything that would be worse than the suffering of one Jones in the “Transmitter Room Problem”)? You got me curious.

SummaryBot @ 2025-01-29T20:54 (+1)

Executive summary: The Light Cone Solution proposes a resolution to the Transmitter Room Problem by asserting that the universe's finiteness imposes limits on the aggregation of mild discomfort, ensuring that extreme suffering of an individual should take priority over collective but minor distress.

Key points:

- Biting the Bullet Approach: Some argue that extreme suffering can be outweighed by the aggregate discomfort of a vast number of individuals, though this is counterintuitive and relies on our difficulty grasping large numbers.

- Infinite Disutility Approach: This perspective suggests that extreme suffering has infinite negative utility, making it impossible to be counterbalanced by any finite aggregation of minor discomfort, though it raises issues like treating one and two extreme cases as equally bad.

- The Light Cone Solution: This approach assumes a finite observable universe, ensuring that even an arbitrarily large audience remains finite, meaning extreme suffering can still be assigned sufficiently negative finite utility to outweigh dispersed mild discomfort.

- Implications for Effective Altruism: The solution suggests that prioritizing the avoidance of extreme suffering may be a more immediate moral imperative compared to ensuring a valuable long-term future.

- Unresolved Questions: The argument depends on the assumption that sentient beings remain finite in number over time, raising questions about the universe’s future habitability and whether suffering should take priority over future-oriented existential risks.

- Call for Further Discussion: The post invites input on whether this resolution has been discussed elsewhere and welcomes alternative perspectives on balancing extreme suffering against dispersed minor discomfort.

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.