The Charity Trap: Brain Misallocation

By DavidNash @ 2025-10-23T12:04 (+181)

This is a linkpost to https://gdea.substack.com/p/the-charity-trap-brain-misallocation

In Ugandan villages where non-governmental organisations (NGOs) hired away the existing government health worker, infant mortality went up.

This happened in 39%[1] of villages that already had a government worker. The NGO arrived with funding and good intentions, but the likelihood that villagers received care from any health worker declined by ~23%.

Brain Misallocation

“Brain drain”, - the movement of people from poorer countries to wealthier ones, has been extensively discussed for decades[2]. But there’s a different dynamic that gets far less attention: “brain misallocation”.

In many low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), the brightest talents are being incentivised towards organisations that don’t utilise their potential for national development. They’re learning how to get grants from multilateral alphabet organisations rather than build businesses or make good policy. This isn’t about talent leaving the country. It’s about talent being misdirected and mistrained within it.

Examples

Nick Laing in northern Uganda describes the talent drain:

Last year, one of our best nurses left one of our rural health centres. With no warning and without telling anyone. It was the 3rd nurse that year who left for an NGO job. We rushed to replace him, but it put the only remaining nurse there under a lot of stress, and I’m sure patients weren’t cared for as well in the meantime. Our replacement wasn’t as good. I didn’t hear the nurse who left again until 6 months later, last week. He came to apologise for leaving abruptly. He said he felt really bad about it, that he had let his fellow staff and the patients down. He’s a great guy and it was good to catch up and reconcile everything. When I asked him why he left for the NGO job, he looked at me as if it was a stupid question.

“The money was too much, of course”

This same dynamic affects would-be entrepreneurs and private sector workers, not just government employees and local health centres.

The wage differential driving this is substantial. Ivan Gayton’s experience with Médecins Sans Frontières in Burundi illustrates the scale. In 2003, MSF paid unskilled labour $1/day when the local market rate was 25 cents.

Ivan: …I mentioned…this back of the envelope calculation that we were 75% of the local economy…we destroyed and distorted the local economy completely; as development practice that would’ve been utterly and completely unethical.

The only justification for doing something like that is an acute emergency, which it was, it was nigh on a hundred thousand people with literally no access to healthcare whatsoever. The amount of avoidable suffering and death that was going on that we could actually alleviate was something that, you know, in sort of humanitarian practice, I guess we arrogate to ourselves the idea that we can, in a sufficiently emergency situation, justify doing things that would be unethical development practice.

Elizabeth: Do you think the village was worse off for having the hospital located in their village?

Ivan: oh yeah. Because we obviously brought this flood of money in, but where does the money go? The doctors and nurses, they’re not even local. They’re from the capital city. So you’re bringing in people from the capitol who then lord it over the local people, price of food jumps up, price of accommodation goes insane. The trickle down opportunities are to be sex workers and cleaners and, you know, servants for these, for these newly created royalty.

Elizabeth: you might hope that if the price of food goes up, but their wages are also going up because they’re working for the hospital or tangentially, then that would compensate?

Ivan: Well yeah. For the people who are already, you know, have access to the labor market and are already able to sort of get in on that. Sure. I mentioned that I actually, I deliberately kind of rotated through the villagers to give lots of people a chance, but still, if you’re not one of the people who gets a chance or even ever had a chance, or was somebody who’s, you know, on the outs with the local powerful people, then we, as these foreigners providing these jobs, we never even see those people.

They don’t even get to apply for a job with us. We never even know of their existence. So those people, now, the price of everything is jumped. There’s a bunch of newly, much more wealthy people around them, and they’re excluded from that. They don’t see any of the benefit and all of the harm. So it’s, it’s terrible.

While MSF could justify this as an acute emergency response, the economic distortion was huge. These wage premiums, sustained over time across thousands of NGOs, fundamentally reshape who works where and develops what skills.

Kenya alone has over 11,000 NGOs employing 70,000+ people. That’s roughly equivalent to staffing 15 mid-sized hospitals, 700 secondary schools or hundreds of larger companies. Instead, it’s distributed across thousands of small projects, many of which are likely less effective than the services they replace.

The Incentive Trap

This isn’t about NGOs being malicious, they’re responding to incentives. So are workers. But rational individual decisions can create collective dysfunction.

No one is making deliberately bad choices. A talented graduate earning $150/month gets offered $600/month by an international NGO. She takes it. Why wouldn’t she? An NGO needs skilled staff and can afford to pay. Why wouldn’t they hire her?

But multiply this by thousands of decisions, and you get a system where the brightest people learn to write grant proposals instead of build businesses and satisfy donor reporting requirements instead of navigating local politics.

When a significant chunk of a country’s most educated young people end up in the NGO ecosystem, several patterns might emerge.

- Accountability runs upward, not downward

- Staff learn to focus on reporting metrics, not respond to community needs or political/business realities. The skills for navigating aid bureaucracy don’t transfer to navigating citizen or customer demands

- Scattered impact

- Rather than concentrating intellectual capital in sectors that could drive economic growth, talent gets distributed across numerous small initiatives with limited scale

- Skills mismatch

- The skills NGOs cultivate such as grant writing, donor reporting, international frameworks, aren’t the ones most needed for building competitive local enterprises or effective public institutions

- Wrong networks for local impact

- Career advancement in NGOs means building relationships with other international organisations, donors and expatriate staff. The connections that matter for building local institutions are less developed

- Sector hopping following funding waves

- When donor priorities shift from health to education to climate, talented people follow. There is less deep expertise in one sector because career incentives reward flexibility to chase funding trends

When Help Becomes Harm

A study in Ghana found that when NGOs entered communities, government funding decreased by 6.8% in NGO-active sectors (even as it increased by 7.4% in areas where the NGO was not focused). Money flowed away from government institutions that villagers had previously relied upon and into new programs sponsored by the NGO.

This les to overall villager well-being (measured across food security, education, health, nutrition, environment and economic livelihood) decreased by 0.1 standard deviations after the NGO’s arrival. These villagers had historically relied more on government institutions, so when the NGO displaced those without providing better alternatives, they suffered most.

One theory for the underperformance was that the NGO encouraged citizens to spend more time engaging with relatively powerless local authorities rather than the higher-level political work that could actually improve wellbeing.

Conclusion

This could be wrong. Maybe NGO experience provides valuable skills people later use elsewhere. Maybe in contexts with few good jobs, NGOs are the best available option for keeping talented people in-country and employed.

There are also variations in government pay as well with some countries having relatively high pay for government workers with very little extra productivity to show for it.

But if there’s something to the idea of brain misallocation, it could reframe how we think about development aid effectiveness. Not just “does this project work?” but “what is this doing to local human capital allocation?”

I think NGOs and donors need to ask uncomfortable questions. When you pay staff 2x local rates, where are those people coming from? What would they be doing otherwise? Are you strengthening or weakening regional capacity? What role are you playing in the broader talent ecosystem?

Also job seekers in LMICs facing this choice deserve better options. The problem isn’t that NGOs pay too much, it’s that private sector opportunities pay too little or don’t exist. This is ultimately about governance and economic development failures, with NGO salaries as a symptom not a cause.

- ^

Deserranno, Erika, Aisha Nansamba, and Nancy Qian. 2020. “Aid Crowd-Out: The Effect of NGOs on Government-Provided Public Services.”

- ^

In some cases, such as Filipino nurses working abroad, it likely creates positive outcomes through remittances, skill development and international networks, but this may not hold for smaller countries or those affected by conflicts.

NickLaing @ 2025-10-24T21:56 (+62)

Thanks so much for writing this @DavidNash. I think that this awkward but important negative externality is little discussed in EA Global health circles, and I've never seen seen this included as a negative adjustment in a cost-effectiveness analysis (would be tricky tho). Hiring the best people away from their burgeoning new business or a government job could cause a horrendous counterfactual of lost value - that of course you'll never see or know.

I think many NGOs unfortunately see their hiring situation a kind of failure of game theory. For the individual NGO the best option seems to be to hire the best worker they can for a high salary. NGOs don't co-operate and pay market wage, so most NGOs just defect and they all pay more. You then get a weird NGO world which operates on a different plane from the local market. When I talk to NGO leader and they mostlyadmit that paying so much is bad for the reasons you outline, but then shrug and respond.

"what choice do we have to get the best staff"

I think in general though the NGOs are wrong even about having to pay this much to get super capable people. Unemployment rates are so high in LMICs, that there are thousands of super talented and capable people that would happily take a 30% or 50% lower salary that than they are paying - and with support and guidance would often do a great job. This might not be the case at top management level, but holds at most other levels of an organisation.

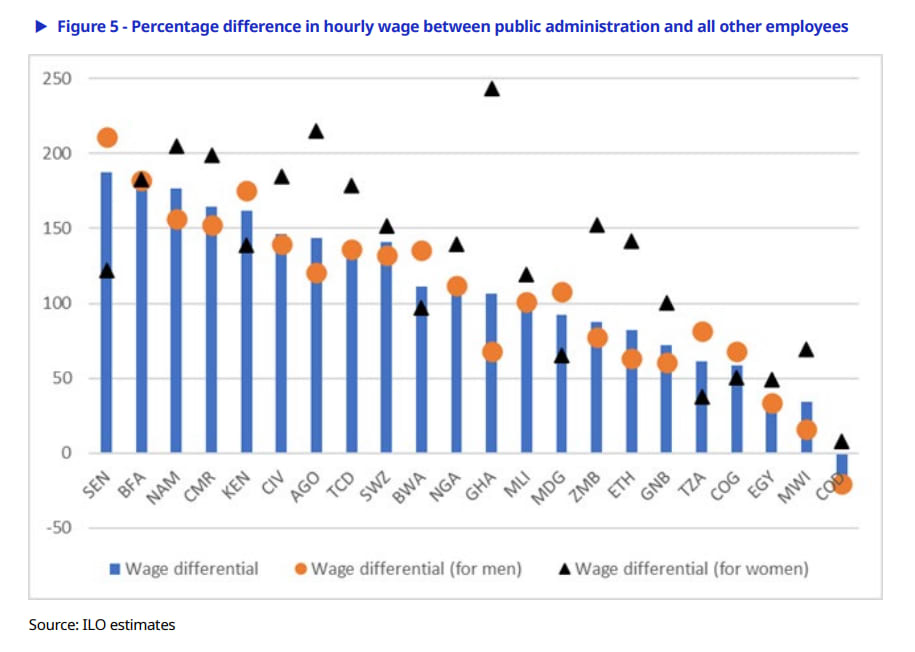

Pushback - Government pays HIGH

One pushback I have, is that "There are also variations in government pay as well with some countries having relatively high pay for government workers" misrepresents the situation - government pay is usually much higher than the market. In Uganda, government jobs are seen as the "Mecca" because they pay so much more than the market, and often at least as much as NGO jobs. Many NGOs then make the mistake of benchmarking to government salaries even though that doesn't represent market salaries at all. I think many government salaries are absurdly high in Uganda, and this matches the situation in other countries. This International Labour Org listshows that in most Sub-Saharan African countries government salaries average more than double the private market, which is kind of crazy...

And to back that up here's my experience of certificate nurse salaries in Uganda.

Goverment - $350 monthly

NGO - $300 monthly (and you have to work harder than in government)

Us - $130 monthly (junior staff)

Other private - $100 monthly

I think your arguments against the problem are weak, you say "This could be wrong. Maybe NGO experience provides valuable skills people later use elsewhere. Maybe in contexts with few good jobs, NGOs are the best available option for keeping talented people in-country and employed. This seems like a straw man to me, because the counterfactual isn't hiring no-one, its paying people less. Why not just hire 2 people at slightly above the market rate rather than one for double the rate as is common practice. Then more people get the skills to later use elsewhere and more people get decent jobs which could keep them in-country.

I think NGOs could largelty solve this problem through benchmarking against similar private sector salaries, then maybe add 20%-30% to that. This should be a good balance where you can

1. Hire great staff

2. Retain your staff

3. Avoid misallocation of staff from other more (or similarly) important work

One positive development is that NGO salaries have reduced over the last few years, in Uganda at least. I think that NGO budgets have been tighter, and also NGOs have realised they don't actually need those high salaries to retain staff. Post USAID I hope this situation improves even more.

One area salaries are still stupid-high is in research projects run by foreign universities/institutions. I think foreign researchers are usually so far removed from local realities they have even less of a clue about the local economy than NGOs. At OneDay Health we've been involved in a couple of research projects recently, and salaries people in this field have been wanting are even higher than I've seen in NGOs - sometimes close to on par with Western Salaries. I actually cracked up laughing on the phone at one salary request (probably rude of me).

A parting shot

I want to call out EA-affiliated orgs as often no better than the average here. GiveWell funded Orgs like Clinton Health Access Initiative (CHAI) and PATH follow the pattern @DavidNash describes. One time a staff from (i think, can't remember 100 percent( one of these orgs exclaimed...

"we have this amazing ex-government worker who really knows how government works and can help us make change there".... Sad story...

When I balked at the high salaries in a CHAI Project here, @GiveWell responded with their unusually wonderful transparency.

"Our understanding is that salaries are set based on globally-benchmarked salary ranges and localized equity adjustments to account for organizational equitable pay standards and differential cost of living across different geographies. A portion of the compensation costs is also due to benefits (such as health insurance) that may be standard to each location.

To which I would respond - yes if that's the approach, you'll end up paying extremely high salaries and often pinch staff from similarly/more important work. Better to benchmark against the market, not "Organisational equitable pay standards". Also (by the by) I would doubt that health insurance is "standard" in any Sub-Saharan country.

Elena Ciobanu @ 2025-10-27T18:36 (+3)

Interesting, are there NGOs in LMICs that pay their staff 20% more than the market pay?

NickLaing @ 2025-10-28T05:19 (+5)

hey there interesting question! As a policy I would doubt it. interestingly sometimes NGO policies pay as minority of jobs at or below market rate. for example a NGO hospital close to my home pays everyone with a degree the same amount. So most of their staff then get 50 to 100 percent more than they market rate, but they struggle to even hire radiographers (there's a shortage) who get paid double other degree holders on the open market. The health center I work at (which pays 20% more than market) recently had to hire a radiographer paid twice as much as the in-charge of the facility!

At OneDay health we do something like that, although it's not an official policy. Although In management positions I'll be honest that we pay a bit more and say I'm partially guilty of my own accusations. Not even in the ballpark of many NGOs though.

Elena Ciobanu @ 2025-10-28T06:18 (+1)

Interesting. Thank you for explaining!

MattJ @ 2025-11-06T20:53 (+12)

Thank you David, for an important and well-argued piece. The "brain misallocation" trap is a concept that resonates deeply for me.

I previously worked in an HQ role at MSF, and I can confirm that the central tensions you highlight from 2003 are not only real but continue to be a subject of active, near constant, and often painful debate within the organization.

Your post and Ivan’s account captures two of the most difficult ethical binds that organizations like MSF face:

1. Pay Inequity: The challenge of "equity" between internationally-hired and locally-hired staff is a massive, unresolved issue. It's a challenging knot to untangle. If you pay a global "fair" wage, you completely distort the local market, becoming the "trap" you describe. If you pay purely local wages, you struggle to deploy specialized international staff, and you create a deeply visible and demoralizing "caste" system within the team. This isn't an excuse, but it's a constant source of moral injury and operational challenge.

2. The "Slippery Slope": Your post also hits on the tension between emergency and development. MSF's identity is built on emergency response: show up, treat the cholera (or malaria, or measles, or…) patch the wounds, and leave. The problem is that you often come for the emergency but stay because there is no or a poorly functioning health system. This is the true "slippery slope." The team and support on the ground often can't ethically leave, there is no option for a transfer of care, so they know people will die the day they pack up. But by staying, the organization becomes a parallel or de facto health system, which does contribute to the long-term distortions and dependencies the original post critiques.

This is where I think we need to draw a distinction, and where I find an EA-informed justification for the emergency component of this work.

The critique of "brain misallocation" is most powerful when applied to the development sector, which operates in relatively stable (even if low resource) environments. In that context, long-term, systemic change is the goal, and misallocating the best local minds to aid bureaucracy is a crucial (and often neglected) negative externality.

However, "pure" emergency work (like in an active conflict, a natural disaster, or a major outbreak) operates under a different ethical framework.

• Tractability & Neglectedness: In a true emergency, the "local system" is not just weak; it it may be relatively non-existent, overwhelmed, or actively hostile. The counterfactual is not "this nurse would be working for the local government." The counterfactual may be "this nurse would be a refugee, dead, or working with no supplies or medicine."

• The Triage Model: The value proposition of an organization like MSF is not systemic change; it is immediate, tractable, and measurable harm reduction. It is a triage model. The goal is not to fix the country's economy or governance (the needed underlying solutions). The goal is to stop this specific person from dying of this specific bullet wound or this specific case of cholera, today.

From an EA perspective, this is a powerful justification. The intervention is highly tractable (we know how to treat cholera) and serves a highly neglected population (those who will die in the next 24 hours without intervention).

The moral and strategic tragedy is when the triage (emergency) is forced to become the long-term ward (development) because the "underlying solutions" - stable governance, peace, infrastructure - are so often in retreat.

This doesn't invalidate the original post's critique. In fact, it reinforces it. The "Trap" is what happens when the emergency response model is incorrectly or indefinitely applied to a development problem. It highlights the immense difficulty of working in a world where the problems are so deep that even the solutions can cause harm.

P.S. I also want to humbly acknowledge that critiques of aid's unintended consequences are not new, and are most powerfully articulated by economists with direct experience in the Global South. This is a central thesis of Dambisa Moyo’s "Dead Aid," where she specifically details how the aid industry can siphon talent and distort local markets and governance.

Lucas Lewit-Mendes @ 2025-10-29T21:47 (+11)

This is somewhat troubling. Do you think this makes some of GiveWell's grants potentially net negative?

DavidNash @ 2025-10-29T23:36 (+5)

I haven't looked into it, I think GiveWell recommended charities make up a very small percentage of most countries NGO workforce, so it seems unlikely to be much of a difference.

NickLaing @ 2025-10-30T03:45 (+9)

i agree that is unlikely to make a paradigm shifting different to their cost effectiveness, but i doubt see how the "percentage of an NGO workforce" employed is important to answer this question? i would think about it something like (good done - this negative externality).

Lucas Lewit-Mendes @ 2025-10-29T23:44 (+1)

That makes sense, thanks David. I note that GiveWell often works with governments to scale up a program (e.g. CHAI), which seems like it would protect against the risk of a decrease in government funding.

On the other hand, New Incentives is opposed by government.

NickLaing @ 2025-10-30T03:45 (+4)

great question Lucas! i think it's highly unlikely (verging on implausible) that this could make a GiveWell grant net negative - those particular charities do so much good, that even in the unlikely scenario that a GiveWell charity plucked many of their staff from high good-yielding jobs i struggle to imagine it could pull their work to net negative.

I also doubt it could lower their cost effectiveness by more than say 2x, but this is intuition. A 2x negative multiplier though would be significant and important.

Those staff they hire will also be replaced in time as well to some extent, which mitigates some of the harm

like I mentioned above in my reply though this problem could be remedied relatively easily by GiveWell chaities in most cases by making sure they pay less than high government salaries for most of all positions.

Lucas Lewit-Mendes @ 2025-10-31T11:29 (+1)

This makes sense, thanks Nick! I suspect the larger positive/negative externality is the long-run effect on the strength of government health systems, which seems likely to be positive for most GW-funded programs (since those programs usually leverage government staff and funding).

NickLaing @ 2025-10-31T12:02 (+2)

hey Lucas i think you are often right, although there can be issues with dependency created too. i think factoring in post- program externalities is tricky but definitely worth thinking about qualitatively at the very least

Lucas Lewit-Mendes @ 2025-11-01T23:59 (+1)

Thanks Nick, what do you mean by issues with dependency? Is that the government becoming dependent on an NGO?

bhrdwj🔸 @ 2025-10-24T11:41 (+6)

100%. This is what is happening kwa ground in LICs and LMICs.

Nithya @ 2025-11-06T20:15 (+4)

This is an important subject, thanks for writing about it. I want to share a couple of points, I don't usually write long posts or comments, so please excuse any misplaced brevity.

- NGO jobs are not all targeting grant writing and networking with other NGOs. The paper you cite - Desarrano et al is discussing a case where community health workers move from govt to NGO. It is not that the skills they learn aren't valuable. The findings of the paper are far more nuanced about what is causing negative impact on health outcomes. In this specific case, the NGO actually doesn't pay the community workers with aid money, they pay them a commission on sales of products. This raises an important question too: are NGOs being forced to rely on sales to pay their staff.

- There are so many private organizations where staff are not employed in a manner that is productive for the society - including increasing profit margins despite negative externalities and networking, so the counterfactual is not automatically "more productive" for the economy. But you make an important point about needing to think about local impact beyond the health outcomes. That is a difficult and expensive enterprise but some researchers are doing that e.g., long term followup studies on deworming and cash.

These salaries are high partly because of lack of skilled workforce, so programs focused on capacity building could alleviate some of those concerns.

DavidNash @ 2025-11-07T09:48 (+2)

Thanks for adding this Nithya, I agree with both points. This post was more about raising a question I hadn't seen discussed much in EA spaces and so there is likely research that supports or weakens the argument I didn't come across.

My general impression is that non profits tend to teach skills that are less valuable longer term when globally 90% of jobs are in the private sector, even if the skills are valuable to some extent.

It's also about who is learning the skills, if the people who would have been the top 5% of entrepreneurs/leaders/scientists are not working in those spaces that seems like a loss for those countries.

Rasool @ 2025-11-03T00:25 (+4)

There's a transcript of the Ivan Gayton podcast, and other discussion, here

Kerry Nasidai @ 2025-12-08T08:58 (+3)

Love this, David! It really resonates with an article I read recently (different context, same principle -- (https://www.ft.com/content/f01c0d6d-9546-4c3d-b1f0-18adc301ce11)): the brightest minds often start out highly ambitious and mission-driven, convinced they’ll change the world. But over time they become locked in by the “golden handcuffs.” It’s partly the money (salaries, allowances, school fees), but also the prestige and proximity to global power circles i.e. flying to international conferences, the perceived legitimacy and intelligence of colleagues from the US/Europe, and the social capital that comes with these roles.

Having smart people in the development/NGO sector isn’t the issue, in fact, it’s essential, as long as they are able to work effectively and drive real outcomes. The problem is that much of the development world has fallen into the very traps it criticizes governments for: bureaucracy, slow decision-making, inconsistent strategic direction, and limited transparency on use of funds and results. That’s when the sector risks becoming a place of misallocated talent/“brain waste”, despite the good intentions.