Literature Review: Distributed Teams

By Elizabeth @ 2019-04-16T17:57 (+66)

Introduction

Context: Oliver Habryka commissioned me to study and summarize the literature on distributed teams, with the goal of improving altruistic organizations. We wanted this to be rigorous as possible; unfortunately the rigor ceiling was low, for reasons discussed below. To fill in the gaps and especially to create a unified model instead of a series of isolated facts, I relied heavily on my own experience on a variety of team types (the favorite of which was an entirely remote company). This document consists of five parts:

- Summary

- A series of specific questions Oliver asked, with supporting points and citations. My full, disorganized notes will be published as a comment.

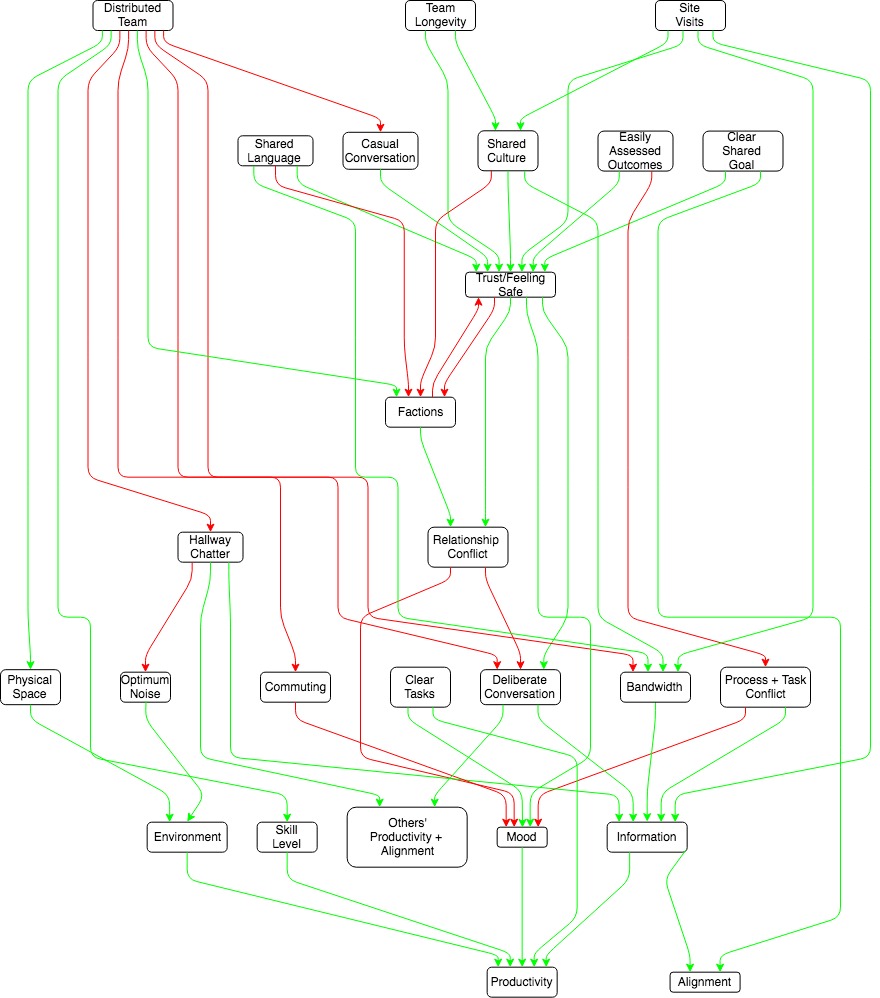

My overall model of worker productivity is as follows:

Highlights and embellishments:

- Distribution decreases bandwidth and trust (although you can make up for a surprising amount of this with well timed visits).

- Semi-distributed teams are worse than fully remote or fully co-located teams on basically every metric. The politics are worse because geography becomes a fault line for factions, and information is lost because people incorrectly count on proximity to distribute information.

- You can get co-location benefits for about as many people as you can fit in a hallway: after that you’re paying the costs of co-location while benefits decrease.

- No paper even attempted to examine the increase in worker quality/fit you can get from fully remote teams.

Sources of difficulty:

- Business science research is generally crap.

- Much of the research was quite old, and I expect technology to improve results from distribution every year.

- Numerical rigor trades off against nuance. This was especially detrimental when it comes to forming a model of how co-location affects politics, where much that happens is subtle and unseen. The most largest studies are generally survey data, which can only use crude correlations. The most interesting studies involved researchers reading all of a team’s correspondence over months and conducting in-depth interviews, which can only be done for a handful of teams per paper.

How does distribution affect information flow?

“Co-location” can mean two things: actually working together side by side on the same task, or working in parallel on different tasks near each other. The former has an information bandwidth that technology cannot yet duplicate. The latter can lead to serendipitous information sharing, but also imposes costs in the form of noise pollution and siphoning brain power for social relations.

Distributed teams require information sharing processes to replace the serendipitous information sharing. These processes are less likely to be developed in teams with multiple locations (as opposed to entirely remote). Worst of all is being a lone remote worker on a co-located team; you will miss too much information and it’s feasible only occasionally, despite the fact that measured productivity tends to rise when people work from home.

I think relying on co-location over processes for information sharing is similar to relying on human memory over writing things down: much cheaper until it hits a sharp cliff. Empirically that cliff is about 30 meters, or one hallway. After that, process shines.

List of isolated facts, with attribution:

- “The mutual knowledge problem” (Cramton 2015):

- Assumption knowledge is shared when it is not, including:

- typical minding.

- Not realizing how big a request is (e.g. “why don’t you just walk down the hall to check?”, not realizing the lab with the data is 3 hours away. And the recipient of the request not knowing the asker does not know that, and so assumes the asker does not value their time).

- Counting on informal information distribution mechanisms that don’t distribute evenly

- Silence can be mean many things and is often misinterpreted. E.g. acquiescence, deliberate snub, message never received.

- Lack of easy common language can be an incredible stressor and hamper information flow (Cramton 2015).

- People commonly cite overhearing hallway conversation as a benefit of co-location. My experience is that Slack is superior for producing this because it can be done asynchronously, but there’s reason to believe I’m an outlier.

- Serendipitous discovery and collaboration falls off by the time you reach 30 meters (chapter 5), or once you’re off the same hallway (chapter 6)

- Being near executives, project decision makers, sources of information (e.g. customers), or simply more of your peers gets you more information (Hinds, Retelny, and Cramton 2015)

How does Distribution Interact with Conflict?

Distribution increases conflict and reduces trust in a variety of ways.

- Distribution doesn’t lead to factions in and of itself, but can in the presence of other factors correlated with location

- e.g. if the engineering team is in SF and the finance team in NY, that’s two correlated traits for fault lines to form around. Conversely, having common traits across locations (e.g. work role, being parents of young children)] fights factionalization (Cramton and Hinds 2005).

- Language is an especially likely fault line.

- Levels of trust and positive affect are generally lower among distributed teams (Mortenson and Neeley 2012) and even co-located people who work from home frequently enough (Gajendra and Harrison 2007).

- Conflict is generally higher in distributed teams (O’Leary and Mortenson 2009, Martins, Gilson, and Maynard 2004)

- It’s easier for conflict to result in withdrawal among workers who aren’t co-located, amplifying the costs and making problem solving harder.

- People are more likely to commit the fundamental attribution error against remote teammates (Wilson et al 2008).

- Different social norms or lack of information about colleagues lead to misinterpretation of behavior (Cramton 2016) e.g.,

- you don’t realize your remote co-worker never smiles at anyone and so assume he hates you personally.

- different ideas of the meaning of words like “yes” or “deadline”.

- From analogy to biology I predict conflict is most likely to arise when two teams are relatively evenly matched in terms of power/ resources and when spoils are winner take all.

- Most site:site conflict is ultimately driven by desire for access to growth opportunities (Hinds, Retelny, and Cramton 2015). It’s not clear to me this would go away if everyone is co-located- it’s easier to view a distant colleague as a threat than a close one, but if the number of opportunities is the same, moving people closer doesn’t make them not threats.

- Note that conflict is not always bad- it can mean people are honing their ideas against others’. However the literature on virtual teams is implicitly talking about relationship conflict, which tends to be a pure negative.

When are remote teams preferable?

- You need more people than can fit in a 30m radius circle (chapter 5), or a single hallway. (chapter 6).

- Multiple critical people can’t be co-located, e.g.,

- Wave’s compliance officer wouldn’t leave semi-rural Pennsylvania, and there was no way to get a good team assembled there.

- Lobbying must be based in Washington, manufacturing must be based somewhere cheaper.

- Customers are located in multiple locations, such that you can co-locate with your team members or customers, but not both.

- If you must have some team members not co-located, better to be entirely remote than leave them isolated. If most of the team is co-located, they will not do the things necessary to keep remote individuals in the loop.

- There is a clear shared goal

- The team will be working together for a long time and knows it (Alge, Weithoff, and Klein 2003)

- Tasks are separable and independent.

- You can filter for people who are good at remote work (independent, good at learning from written work).

- The work is easy to evaluate based on outcome or produces highly visible artifacts.

- The work or worker benefits from being done intermittently, or doesn’t lend itself to 8-hours-and-done, e.g.,

- Wave’s anti-fraud officer worked when the suspected fraud was happening.

- Engineer on call shifts.

- You need to be process- or documentation-heavy for other reasons, e.g. legal, or find it relatively cheap to be so (chapter 2).

- You want to reduce variation in how much people contribute (=get shy people to talk more) (Martins, Gilson, and Maynard 2008).

- Your work benefits from long OODA loops.

- You anticipate low turnover (chapter 2).

How to Mitigate the Costs of Distribution

- Site visits and retreats, especially early in the process and at critical decision points. I don’t trust the papers quantitatively, but some report site visits doing as good a job at trust- and rapport-building as co-location, so it’s probably at least that order of magnitude (see Hinds and Cramton 2014 for a long list of studies showing good results from site visits).

- Site visits should include social activities and meals, not just work. Having someone visit and not integrating them socially is worse than no visit at all.

- Site visits are more helpful than retreats because they give the visitor more context about their coworkers (chapter 2). This probably applies more strongly in industrial settings.

- Use voice or video when need for bandwidth is higher (chapter 2).

- Although high-bandwidth virtual communication may make it easier to lie or mislead than either in person or low-bandwidth virtual communication (Håkonsson et al 2016).

- Make people very accessible, e.g.,

- Wave asked that all employees leave skype on autoanswer while working, to recreate walking to someone’s desk and tapping them on the shoulder.

- Put contact information in an accessible wiki or on Slack, instead of making people ask for it.

- Lightweight channels for building rapport, e.g., CEA’s compliments Slack channel, Wave’s kudos section in weekly meeting minutes (personal observation).

- Build over-communication into the process.

- In particular, don’t let silence carry information. Silence can be interpreted a million different ways (Cramton 2001).

- Things that are good all the time but become more critical on remote teams

- Clear goals/objectives

- Clear metrics for your goals/objectives

- Clear roles (Zacarro, Ardison, Orvis 2004)

- Regular 1:1s

- Clear communication around current status

- Long time horizons (chapter 10).

- Shared identity (Hinds and Mortensen 2005) with identifiers (chapter 10), e.g. t-shirts with logos.

- Have a common chat tool (e.g., Slack or Discord) and give workers access to as many channels as you can, to recreate hallway serendipity (personal observation).

- Hire people like me

- long OODA loop

- good at learning from written information

- Good at working working asynchronously

- Don’t require social stimulation from work

- Be fully remote, as opposed to just a few people working remotely or multiple co-location sites.

- If you have multiple sites, lumping together similar people or functions will lead to more factions (Cramton and Hinds 2005). But co-locating people who need to work together takes advantage of the higher bandwidth co-location provides..

- Train workers in active listening (chapter 4) and conflict resolution. Microsoft uses the Crucial Conversations class, and I found the book of the same name incredibly helpful.

Cramton 2016 was an excellent summary paper I refer to a lot in this write up. It’s not easily available on-line, but the author was kind enough to share a PDF with me that I can pass on. My full notes will be published as a comment on this post.

Milan_Griffes @ 2019-04-16T19:03 (+8)

-Distribution decreases bandwidth and trust (although you can make up for a surprising amount of this with well timed visits).

-Semi-distributed teams are worse than fully remote or fully co-located teams on basically every metric. The politics are worse because geography becomes a fault line for factions, and information is lost because people incorrectly count on proximity to distribute information.

+1 to these two points. (Elizabeth & I both worked at Wave, which is distributed-first.)

Relatedly, Matt of Wordpress just published a nice piece on distributed work. (Wordpress is probably the biggest distributed-first company.)

Elizabeth @ 2019-04-16T17:57 (+6)

My disorganized, unformatted notes.

Understanding Conflict in Geographically Distributed Teams: The Moderating Effects of Shared Identity, Shared Context, and Spontaneous Communication

Pamela J. Hinds, Mark Mortensen 2005

- “t shared identity moderated the effect of distribution on interpersonal conflict and that shared context moderated the effect of distribution on task conflict”

- “spontaneous communication was associated with a stronger shared identity and more shared context, our moderating variables. Second, spontaneous communication had a direct moderating effect on the distribution-conflict relationship, mitigating the effect of distribution on both types of conflict. W”

Diversity in team composition, relationship conflict and team leader support on globally

distributed virtual software development team performance

Wickramasinghe, V.

Nandula, S.

University of Moratuwa, Sri Lanka.

- “diversity in team composition leads to relationship conflict, relationship conflict leads to team performance, and team leader support moderates the latter relationship”

- Never meeting in person is bad

- Diversity -> relationship conflict, but that’s probably not the problem here

- This is offshoring, which has class and quality implications

- “, a mean value of 3.67 suggests a considerably high level of conflict between team members. “

- Leadership is good

(PDF available on request)

Insights for Culture and Psychology from the Study of Distributed Work Teams

Catherine Cramton

- Screw you google books and your disabling of copy/paste and hiding of pages

- The mutual knowledge problem: people act on disparate knowledge without knowing the knowledge is disparate

- Note: I skipped descriptions of problems for which I had already described the paper they were based on.

- “Language asymmetries” are a big deal.

- “Strategies included avoiding conversations and meetings at which the lingua franca would be required, deleting correspondence unread, leaving meetings early, trying to control attendance at meetings to exclude speakers of the less familiar language, and switching languages in the middle of meetings.”

- “For example, on the Indian side, team leaders were active work monitors. The importance of tasks was judged by how often the team leader asked about progress. Lack of active leader monitoring indicated to Indian developers that a task was unimportant. This permitted developers to agree to all requests, while tacitly judging the true importance of a task by the level of team lead monitoring. Thus the timing of work was linked to leader monitoring. Work also was often carried out in bursts of activity after a stated deadline had passed. This was because the deadline was understood within culture to be nominal in deference to immediate instructions of superiors.” meanwhile, their German superiors expected to be proactively notified of delays.

http://sci-hub.tw/10.1145/2675133.2675199

In the Flow, Being Heard, and Having Opportunities: Sources of Power and Power Dynamics in Global Teams

Pamela Hinds

Daniela Retelny

Catherine Cramton

2015

- “Over the last 10-15 years, research on global teams has grown dramatically, including investigations of team dynamics [6, 8, 23, 33], communication structure [10, 19], conflict [20, 21], coordination [16, 18] and leadership [11, 40]. Scholars have also studied the use of technology to support [13, 17, 33, 38] and alleviate many of the challenges encountered by globally distributed teams [3, 27, 28]”

- “ Few studies, however, have examined the power dynamics in global teams, particularly the sources of power and how workers respond to power imbalances. This is despite the fact that the distribution of power can have profound and far-reaching effects on individual behavior [9] and team outcomes [2, 41]”

- “Social power has been defined as “asymmetric control over valued resources in social relations””

- “power is more objective whereas status is in the eye of the beholder.”

- “work by French and Raven [15] reported six sources (bases) of power – legitimate (positional), reward, coercive, informational, expert, and referent”

- “ O’Leary and Mortensen [32] who examined the configurational imbalance (relative numbers of team members) across two sites. They found that locations with (numerical) minority subgroups were at a disadvantage compared to locations with a relatively larger number of team members.”

- “They report that separation in time and space accentuated differences in sources of status (social capital), but that the onshore leaders of these teams sometimes shared their resources as a way to renegotiate status differences”

- 9 teams interviewed over 18 months

- “Our analysis suggests that team members at some locations felt that they had less influence and power than those at other locations. Interestingly, it was not only those at headquarters or those collocated with the largest number of team members who felt powerful, although both of these were factors. We found that the sources of power among these globally distributed professionals resided at different locations and fell into three categories; access to information (being in the flow), access to decision makers (being heard), and opportunities for growth. When team members perceived that they had access to these resources, they felt that they could work effectively, influence decisions of importance, and have career opportunities, but if few were present, they expressed frustration and dissatisfaction in their jobs.”

- “, having the expertise located elsewhere created a dependency on team members at another location, which reduced local developers’ sense of power”

- “Having direct access to customers was also a critical resource for developers and varied significantly by location”

- Factors that matter in likelihood of power struggle:

- Being near executives

- Numerical advantage

- Access to customers

- Access to decisionmakers (e.g. prod people)

- Opportunities for growth (terminal goal)

- Team with shared power had equal access to execs and other sources of power

- “Power Contested In 4 of the 9 teams in our study, power was contested, sometimes fiercely. Surprisingly, in all of these teams, the sources of power were relatively evenly split across locations.”

- “in the absence of a powerful organizational boundary (vendor-client), power contests may be less easily and quickly decided”

- “In our analysis, power contests seemed to be dominated by concerns over opportunities for capturing work and for growth.”

- “ perceiving opportunities for growth diluted power contests.”

- “individuals in power are less likely to share knowledge [26, 30]”

- Suggested fixes:

- “ two-way channel between leaders and distant workers that would provide more access to strategic information, more opportunity to contribute to decisions, and more visibility between leaders and distant workers. Visibility, in particular, would need to be bidirectional, “

- Move people to new sites

http://web.stanford.edu/group/WTO/cgi-bin/wp/wp-content/uploads/2014/pub_old/Cramton_Hinds_2005.pdf

SUBGROUP DYNAMICS IN

INTERNATIONALLY DISTRIBUTED

TEAMS: ETHNOCENTRISM OR

CROSS-NATIONAL LEARNING?

Catherine Durnell Cramton and Pamela J. Hinds

http://www.jimelwood.net/students/grips/man_group_comm/cramton_2001.pdf

The Mutual Knowledge Problem and Its

Consequences for Dispersed Collaboration

Catherine Durnell Cramton

- Group projects consisting of two students each from three different schools, sometimes international. Note that there was no control and students are just bad at things, and didn’t have as much time to gel.

- “Five types of problems constituting failures of mutual knowledge are identified: failure to communicate and retain contextual information, unevenly distributed information, difficulty communicating and understanding the salience of information, differences in speed of access to information, and difficulty interpreting the meaning of silence”

- “unrecognized differences inthe situations, contexts, and constraints of dispersed collaborators constitute "hidden profiles" that can increase the likelihood of dispositional rather than situational attribution, with consequences for cohesion and learning”

- “ Mutual knowledge is knowledge that the communicating parties share in common and know they share”

- “Establishing mutual knowledge is important because it increases the likelihood that communication will be understood”

- “ Proceeding without mutual knowledge, people may speak and understand what is said on the basis of their own information and interpretation of the situation, falsely assuming that the other speaks and understands on the basis of that same information and interpretation”

- “ Krauss and Fussell (1990) describe three mechanisms by which mutual knowledge is established: direct knowledge, interactional dynamics, and category membership”

- “It is well established that groups that meet face-to-face tend to dwell on commonly held information in their discussions and overlook uniquely held information...When a group's discussion is mediated by technology, the problem seems to be worse”

- “ The computer-mediated groups exchanged less information overall and took more time doing it. One of the most robust findings concerning the effect of computer mediation on communication is that it proceeds at a slower rate than does face-to-fac”

- “"A delay of 1.6 seconds is sufficient to disrupt the ability of the sender to refer efficiently to the . . . stimuli, despite the fact that the back-channel response is eventually transmitted”

- Computer mediated interactions are less rich, leading people to read too much in to what non-verbals they do get.

- Computer mediated interaction with people you don’t know well creates feelings of “ isolation, anonymity, and deindividuatio”

- It is important that when a problem arises, peolpe attribute it to the correct cause. In particular, don’t blame the person when the situation is the cause

- “ people using computer-mediated communication with remote others they do not know well rely heavily on social categorizations to guide their relationships. The social categorizations provide a basis for affiliation if participants share a significant social identity. However, they also can provide fodder for in-group/out-group dynamics if remote others are seen as belonging to social categories different and less attractive than oneself”

- “The data were contained in an archival dataset that was created in the course of a collaborative project involving graduate business faculty and students located at nine universities on three continents”

- No co-located controls.

- “Despite efforts to make project requirements consistent across all nine universities, differences were discovered as the project unfolded”

- “s. In seven of the 13 teams, conflict escalated to the point that hostile coalitions formed. In five of these teams, members at two sites began to complain about partners at the third site, refusing in some cases to send them pieces of the team's work or put their names on finished work. Two teams evidenced shifting coalitions among subgroups at the three sites”

- “Eventually, Icharacterized five types of problems: (1) failure to communicate and retain contextual information, (2) unevenly distributed information, (3) differences in the salience of information to individuals, (4) relative differences in speed of access to information, and (5) interpretation of the meaning of silence.”

- (1) failure to communicate and retain contextual information

- E.g. Team members refused to schedule group chat and insisted on phone call, but chat was a required part of the project for other team members

- Not informing each other of spring break (which occurred at different times for different schools).

- Not informing team members they were disappearing for other projects or tests

- Assume co-located team members shared more info than they did

- Team members on e-mail missed that other people weren’t included or that their emails were misspelled. “ Sometimes people knew they were exchanging mail with only part of the team, but failed to understand how this affected the perspectives of team members who did not receive the mail, or how it affected the dynamics of the team as a whole”

- People retained resentments that others were “unresponsive”, even when they saw proof the person had attempted to communicate and it was not their fault (e.g. misspelled an e-mail address).

- “In relationships conducted face-to-face, it is a challenging cognitive exercise to interpret a set of facts from the perspective of another person. It is far more difficult to determine how the information before the other party differs from one's own, and then see things from the other's perspective. Geographic dispersion makes these two activities more difficult because of undetected "leaks in the bucket," because partnerseem to have difficulty retaining information about remote locations, and because feedback processes are laborious”

- Private conversations give an inaccurate perception of the pace of work

- Differences in the salience of information

- Confusion to do indirect wording

- “there was a tendency to request feedback from the team indirectly, yet to expect quick responses from everyone”

- Incorrect assumption that everyone had 24/7 access to email. Some could only check email at school

- Physical distance meant that US <-> US communication was faster than US <-> AUS communication (I expect this to be less of an issue now). This meant everyone’s messages were followed by unrelated messages rather than responses. This was “... attributed to remote partners' lack of conscientiousness”

- Got time difference wrong

- People failed to convey which topics in an email were most important. In person you can check comprehension as you go and look for reactions.

- Interpreting Silence

- “t silence had meant all of the following at one time or another: Iagree. I strongly disagree. I am indifferent. I am out of town. I am having technical problems. Idon't know how to address this sensitive issue. I am busy with other things. Idid not notice your question. I did not realize that you wanted a respons”

- This turned out to be a very big deal.

- “ The data suggest four constellations: (1) good performance, task focus, moderate relationship demands, relatively low volume of communication, and low coalition activity; (2) good performance, high task and relationship demands, relatively high volume of communication, and high coalition activity; (3) weaker performance, relatively high volume of communication, many and diverse information problems, and high coalition activity; and (4) weaker performance, relationship focus, task secondary, relatively high volume of communication, and low coalition activity”

- “Information problems seemed to be more damaging to relationships than to task performance”

- Highest-harmony team did not grade that great, perhaps because their unwillingness to disagree meant they didn’t hone each others’ ideas.

- “ there may be a tendency to generalize such social perceptions, particularly negative ones, to the locational subgroup of which a person is a member, which sets in motion in-group/out-group dynamics (Point [7]) that are destructive to group cohesion”

- “ Members of the teams I studied often failed to guess which of the many features of their context and situation differed from the contexts and situations of remote partner”

- “The authors propose that trusting action and demonstrated reliability increase trust in dispersed teams. However, my work suggests that human and technical errors in information distribution may be common in dispersed collaboration, particularly during the early phases of activity. If these are interpreted as failures of personal reliability, they are likely to inhibit the development and maintenance of trust. “

- “ when people work under heavy cognitive load, they become more likely to make personal rather than situational attributio”

https://sci-hub.tw/10.1287/orsc.2013.0869

Situated Coworker Familiarity: How Site Visits Transform

Relationships Among Distributed Workers

Pamela J. Hinds

Stanford University, Stanford, California 94305, phinds@stanford.edu

Catherine Durnell Cramton

- Site visits engender closer co-worker relationships that change behavior upon return to distant sites, continuing the closeness.

- “qualitative study of 164 workers on globally distributed teams”, over 1.5 years

- “Wilson et al. (2006) demonstrate that trust starts lower in mediated groups but develops to levels comparable to face-to-face groups (although pure electronic groups never achieved the same levels of cooperation as those who met face-to-face)”

- “Walther (1992, 1996), for example, leverages social information processing theory to argue that, although the process may be slower, rapport among members of distributed dyads that never meet can eventually exceed that of collocated dyads. Similarly, Wilson et al. (2006) demonstrate that trust starts lower in mediated groups but develops to levels comparable to face-to-face groups (although pure electronic groups never achieved the same levels of cooperation as those who met face-to-face). Field research on virtual teams has also claimed that knowledge repositories are an adequate substitute for face-to-face interaction (Malhotra et al. 2001)”

- “Grinter et al. (1999), for example, report that coworkers who did not meet face-to-face had more difficulty creating rapport and developing a longterm working relationship. Alge et al. (2003) also find that coworkers who met face-to-face and got to know one another before embarking on a mediated collaborative task reported as much openness and trust as those who worked face-to-face the entire time. In an early review, Olson and Olson (2000) conclude that face-toface interaction is important to establishing the conditions necessary for distributed work. In their longitudinal study of three globally distributed teams, Maznevski and Chudoba (2000) further describe how regular faceto-face meetings create the rhythms that enable higherlevel coordination. Touching (e.g., handshakes, pats on the back) and “breaking bread” together also have been found to contribute to a state of communicative readiness among distant workers (e.g., Nardi 2005). With few exceptions, research on distributed work consistently points to the importance of face-to-face contact as a means of building trust and rapport (e.g., Orlikowski 2002), translating locally situated knowledge (Sole and Edmondson 2002), interacting more rapidly on tasks (Crowston et al. 2007), and building social networks (Orlikowski 2002). This research generally suggests that periodic face-to-face interaction plays an important role for distributed workers, although what happens during these encounters remains largely a mystery.”

- “Mortensen and Neeley (2012) that shows that workers who travel to the location of their coworkers have more knowledge, both direct (about their distant coworkers) and reflected (about their own location), and that this knowledge is associated with feelings of closeness and trust”

- “more time together leads to more familiarity, although a plateau seems to be reached fairly quickly in laboratory settings “

- Workers felt more comfortable with distant co-workers after meeting in person.

- Socializing outside work hours was important

- Seeing how co-workers interact with other people is useful

- “n seeing workers acting on their knowledge and working directly with them as they did so that coworkers truly began to understand the capabilities of their coworkers and how they needed to work together to leverage those skills most effectively.”

- “. Informants told us that after site visits, they and their distant coworkers responded in a much more timely manner to emails and requests”

- Not integrating a visitor has a terrible effect on their morale and doesn’t generate any of the benefits of a good visit.

- “We speculate that travel needs to occur on a regular basis with intervals of about six months, plus or minus depending on the ambiguity of the project”

- Both managers and workers need to travel

https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1008&context=mis_facpubs

Bridging Space over Time: Global Virtual Team

Dynamics and Effectiveness

Katherine M. Chudoba

Utah State University

Martha L. Maznevski

University of Virginia

- “We studied three global virtual teams, collecting data over a period of 21 months: 9 months of intensive observation and collection, preceded by 3 months of informal discussions with the teams and their managers, and followed by 9 months of more discussions.”

- “Effective outcomes were associated with a fit among an interaction incident’s form, decision process, and complexity”

- “effective global virtual teams sequence these incidents to generate a deep rhythm of regular face-toface incidents interspersed with less intensive, shorter incidents using various media.”

- “ In some studies face-to-face groups performed better than technology-mediated groups (e.g., Hightower and Sayeed 1996, Smith and Vanecek 1990); in others they performed worse (e.g., Ocker et al. 1995–1996, Straus 1996); in others there was no difference on quality-related outcomes (e.g., Farmer and Hyatt 1994, Valacich et al. 1993). Furthermore, these relationships changed and evolved over time (e.g., Hollingshead et al. 1993). Although task type was often proposed to moderate the relationship between a medium and its effect on performance (e.g., O’Connor et al. 1993), there did not seem to be a consistent pattern of task types for which communications technology was better or worse. Some studies concluded that a combination of media including face-to-face outperformed one without face-to-face (e.g., Ocker et al. 1998).”

- “trust, which was critical to the team’s ability to manage decision processes, could be built swiftly; however, this trust was very fragile.”

- “This basic pattern is defined by regular faceto-face meetings in which the intensity of interaction is extremely high, followed by a period of some weeks in which interaction incidents are less intense. Moreover, the decision process is organized to match this temporal pattern, rather than the other way around”

- MakeTech and SellTech chose the kind of interaction (phone, fax, etc) to match the task, NewTech did not.

https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/3388/10f4e28b8954d8c63c5bcd8b0295e101ff95.pdf

Reflected Knowledge and Trust in Global Collaboration

Mark Mortensen

INSEAD, 77305 Fontainebleau, France, mark.mortensen@insead.edu

Tsedal B. Neeley

Harvard Business School, Harvard University, Boston, Massachusetts 02163,

tneeley@hbs.edu

- “an equally important trust mechanism is “reflected knowledge,” knowledge that workers gain about the personal characteristics, relationships, and behavioral norms of their own site through the lens of their distant collaborators. Based on surveys gathered from 140 employees in a division of a global chemical company, we found that direct knowledge and reflected knowledge enhanced trust in distinct ways”

- “some researchers have argued that trust is more easily generated in collocated settings, because collocated workers are better placed than their distributed counterparts to use behavioral cues to read intentions and foster a collective identity (Frank 1993, Wilson et al. 2006)”

- “t firsthand experience would be positively related to individuals’ reflected knowledge”

- “neither the path linking reflected knowledge to understanding distant collaborators nor the path linking direct knowledge to feeling understood by distant collaborators were significant in our original model”

- “We found significant positive paths linking direct knowledge and understanding collaborators ( = 00531 p < 00001) and linking reflected knowledge to feeling understood by distant others ( = 00281 p < 0005)”

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00692/full

On Cooperative Behavior in Distributed Teams: The Influence of Organizational Design, Media Richness, Social Interaction, and Interaction Adaptation

Dorthe D. Håkonsson1,2,3*, Børge Obel2,4, Jacob K. Eskildsen4 and Richard M. Burton5

- oxytocin increases awareness of others’ emotional states

- “decision makers with a cooperative mindset were more prone to interpret others’ actions as efforts to coordinate. This, in turn was found to increase the quality of their interaction outcomes ”

- “highly motivated liars interacting in a text-based, computer-mediated environment were more successful in deceiving their partners compared to motivated liars interacting face-to-face”

- “media richness reinforces non-cooperative incentives”

- “Peter Thiel writes that “Even working remotely should be avoided, because misalignment can creep in whenever colleagues aren’t together full-time, in the same place, every day”.”

https://www.scirp.org/journal/PaperInformation.aspx?paperID=84181

An Empirical Analysis of Communication on Trust Building in Virtual Teams

Makoto Shinnishi1orcid, Kunihiko Higa2

- Compared 5 teams with text-only communication, “ five teams could use a non-text communication tool through which one can see other member’s situation with a web camera image and a short text message. “

- “use of non-text communication tool did not affect trust building; however, amount of awareness communication affected trust building. Log-in to the communication system at the same time also affected trust building. The findings of this study showed the tendency of awareness communication helping team building trust in the remote environment.”

- Awareness = “knowledge about the work and worker of current and predicted future status and situation.”

https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/e3b9/57e8c1f6a286ce3b8876c12701a073a8f0c5.pdf

Multinational and Multicultural Distributed Teams: A Review and Future Agenda

Stacey L. Connaughton and Marissa Shuffler

- [we should keep studying this]

http://users.ece.utexas.edu/~perry/education/382v-s08/papers/hinds03.pdf

Out of sight, Out of sync: Understanding conflict in distributed teams

Pamela J. Hinds •Diane E. Bailey

- “empirical studies suggest that distributed teams experience high levels of conflict”

- “In this paper, we develop a theory-based explanation of how geographical distribution provokes team-level conflict.”

- “Geographically distributed teams face a number of unique challenges, including being coached from a distance, coping with the cost and stress of frequent travel, and dealing with repeated delays (Armstrong and Cole 2002).”

- “Field studies further indicate that geographically distributed teams may experience conflict as a result of two factors: The distance that separates team members and their reliance on technology to communicate and work with one another.”

- “Armstrong and Cole (2002) reported that conflicts in geographically distributed teams went unidentified and unaddressed longer than conflicts in collocated teams.”

- “t geographical distribution will have a significant impact on each type of group conflict proposed in recent organizational studies: task, affective, and process. Task conflict refers to disagreements focused on work content. Affective conflict (sometimes referred to as relationship or emotional conflict) refers to team disagreements that are characterized by anger or hostility among group members. Process conflict refers to disagreements over the team’s approach to the task, its methods, and its group processes.”

- “task conflict has been found to be beneficial for performance on many traditional teams, but we contend that it will not be so for their distributed counterparts.”

- “Distributed teams enable firms to take advantage of expertise around the globe, to continue work around the clock, and to create closer relationships with far-flung customers. “

- “We contend that all other traits that may be associated with geographical distribution derive from distance or technology mediation, and we consider them in our analysis of these two factors”

- “members of distributed teams may have difficulty establishing a shared context”

- “in a study of the use of new machines in a factory, Tyre and von Hippel (1997) observed that engineers and operators had trouble resolving equipment problems over the phone because the engineers needed to “see for themselves” the technology in context.”

- “When team members have different understandings of the task, task conflict is likely to result (Jehn et al. 1997). Moreover, when team members’ understanding of the issues differs, conflict is difficult to resolve (Brehmer 1976)”

- “Team members who lack a sense of a shared context as a result of distance also are likely to adhere to different norms”

- “site-specific cultures and expectations acted as significant sources of misunderstandings and conflict between distant sites. “

- “Grinter et al. (1999) found that members of distributed software development teams, regardless of the way they structured their work, were “constantly surprised” and confused about the activities of their distant colleagues.”

- “research on friendship suggests that distributed teams will experience less friendship and, thus, less affective conflict.”

- “studies that suggest that time can remedy the relational problems that ensue from technology mediation”

- “Feelings of not “being there” with one’s communication partners stand to prevent distributed team members from sharing relational information that help teams to develop trust”

- “technology mediation engenders negative relational effects that we contend will precipitate affective conflict.”

- “Several problems related to information sharing and seeking emerge from the literature, including uneven distribution of information, unevenly weighted information, and information that resists transmission.”

- “Uneven distribution can occur in at least two ways: Team members may be purposely or accidentally excluded from communications, or members may not reveal information that they uniquely hold.”

- “Purdy et al. (2000) reported that student groups working face to face collaborated more than distributed groups working over video, telephone, or chat”

- “Longitudinal studies report that groups adapt communication technologies to good effect”

- “Over time, effective teams generate a shared team identity.”

- “Distributed teams appear to gain more if they meet early in the development of the group (Kraut et al. 1992), enabling members to form relationships that can be supported over technologies (Armstrong and Cole 2002)”

- “. If distributed teams are able to meet face to face at the points with the most potential for conflict, then conflict may be reduced or diminished.”

- “Establishing collaborative norms, however, may be significantly more difficult in distributed teams.”

Manager control and employee isolation in

telecommuting environments

Nancy B. Kurlanda

, Cecily D. Cooperb,*

2002

- “he primary challenges facing supervisors who manage in telecommuting environments involve clan strategies: fostering synergy, replicating informal learning, creating opportunities for interpersonal networking, and professionally developing out-of-sight employees.”

- Managers dislike teleworking because they can’t see what people are doing

- Telecommuters are worried that they’ll be ignored politically

- “They evaluated employees’ work based not so much on what they did, but on ‘‘how well they did it.”

- “a shift to managing telecommuters only by results may enhance telecommuters’ professional isolation concerns”

- These are individual telecommuters, not distributed teams

https://www.emeraldinsight.com/doi/pdf/10.1108/13527590410556854

Differences between

on-site and off-site

teams: manager

perceptions

Walt Stevenson and

Erika Weis McGrath

- Useless

Distributed Work (The MIT Press) 1st Edition, Kindle Edition

by Pamela J Hinds (Author, Editor), Sara Kiesler (Editor)

- Chapter 4 The Place of Face-to-Face Communication in Distributed Work

Bonnie A. Nardi and Steve Whittaker

- Chapter 5: The (Currently) Unique Advantages of Collocated Work

Judith S. Olson, Stephanie Teasley, Lisa Covi, and Gary Olson

- “ communication frequency among individuals drops considerably with distance and that after about thirty meters, it reaches asymptote. This means that if two people reside more than 30 meters apart, they may as well be across the continent”

- This paper is talking about radical co-location: 6-8 peeps in the same room. Any further than that doesn’t count.

- “Teams who experienced radical collocation—pioneer teams—were much more productive than standard teams at both this company and in the industry as a whole.”

- “These teams produced twice as much as other teams did in their multitasked work, in standard office cubicles, in projects with more variable scoping. The collocated teams got the job done in about one-third the amount of time compared to the company baseline—and even faster than the industry standard. Both of these differences are significant using a z-score against company baseline (p < .001).”

- I think they had other advantages over the control group, such as having only one task. And of course there’s Hawthorne effect.

- “Follow-on teams were even more productive than the pioneer teams; function points per staff month doubled again while cycle time stayed about the same. We believe this second increase has to do in part with the fact that some of the team members now had experience (some pilot team members served on follow-on teams), and there was some organizational learning about how to run and manage such groups.”

- I’m extremely curious how often team members used the available solo offices.

- Productivity measured in function points, so it’s possible they were just better at estimating.

- Morale effects (positive and negative) were more contagious. Even the team with shit morale was more productive than standard teams.

- White boards and sticky notes were very popular

- Tivoli vs. IBM: quite close

- Chapter 6: Understanding Effects of Proximity on Collaboration: Implications for Technologies to Support Remote Collaborative Work

Robert E. Kraut, Susan R. Fussell, Susan E. Brennan, and Jane Siegel

- “ For example, in collaboration at a distance, communication is typically less frequent, characterized by longer lags between messages, and more effortful.”

- Is less frequent a downside?

- “Results showed that even in this environment, pairs of researchers were unlikely to complete a technical report together unless their offices were physically near each other, even if they had previously published on similar topics or worked in the same department in the company. “

- But international collaborations happen

- What tools can replace hallways?

- Elizabeth’s observation: this works better for extroverts and multitaskers

- “ the most important problem is that when conversation is initiated in person, the people must be simultaneously present”

- “ Ancona and Caldwell (1992),demonstrated that problems can arise when people concentrate communication within a supervisory group and fail to exchange enough information with others outside the group”

- Chatrooms are a partial substitute for hallways

- “Because spoken utterances are ephemeral, unlike messages on an answering machine or in a written document, the listener cannot pause or reread the message when some portion is difficult. Again, however, the ability to ask for clarification partially compensates for the ephemeral nature of speech. When there are many listeners, however, it is far more costly for a single one whose attention has wandered to stop the speaker for clarification”

- “ease of local communication and information acquisition may bias the information tracked by a work group, causing them to overattend to local information at the expense of more remote, contextual information.”

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1207/S15327744JOCE1002_2

Telework: Existing Research and Future Directions

Bongsik Shin , Omar A. El Sawy , Olivia R. Liu Sheng & Kunihiko Higa

- Future research should be more rigorous

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1048984307001518

The impact of superior–subordinate relationships on the commitment, job satisfaction, and performance of virtual workers

Author links open overlay panelTimothy D.GoldenaJohn F.Veigab1

- High quality relationships are good

The Good, the Bad, and the Unknown About Telecommuting: MetaAnalysis of Psychological Mediators and Individual Consequences

Ravi S. Gajendran and David A. Harrison

- “Managers who are unwilling to or who lack the training to

- change their management and control styles would likely see

- deterioration in the depth and vitality of their connection with

- telecommuting subordinates”

- Telecommuting led to: increased feelings of autonomy, lower work-life conflict, better supervisor relationships (not statistically significant), no change on co-worker relationships (low intensity only), worse co-worker relationships (high intensity), increased job satisfaction, increase in objective or external (but not self) reported performance, lower turnover intent, less stress, no impact on career prospect feelings.

- This is true even for very high intensity remote work (> ½ time)

- Could be supervisor relationship improved because people were happy they got to co-work.

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0170840607083105?journalCode=ossa (PDF without permalink available on AWS)

Perceived Proximity in Virtual Work: Explaining the Paradox of Far-but-Close

Jeanne M. Wilson, Michael Boyer O'Leary, Anca Metiu, Quintus R. Jett

2008

- “ By understanding what leads to perceived proximity, we also believe that managers can achieve many of the benefits of co-location without actually having employees work in one place.”

- “As team members discover that they share a certain social category, they establish a common ground from which they can work “

- “the more two people identify with some social category, entity or experience (e.g. profession, gender, ethnicity, common political views, shared trauma, etc.), the more common ground they will have between them and, thus, the more proximal they are likely to feel.”

- They use the example of two mothers of young children. I suspect this effect is much stronger if the far-apart people share a trait they don’t share with people nearby.

- “Absent a shared identity, people have a strong tendency toward faulty attributions about others’ motives”

- This is consistent with other research showing people are more likely to commit the fundamental attribution error against distant people.

- “As one subgroup sought to differentiate itself from the other, less communication between the two groups ensued, resulting in even fewer opportunities to discover and develop a shared identity. “

- “an organization with strong structural assurance might have very rigorous hiring standards. As a result, employees of the organization would feel comfortable communicating with distant co-workers — safe in the knowledge that they were dealing with competent and reliable professionals”

- This was definitely present at Google

- “e, the technological infrastructure for open-source projects (version control systems, specialized topic-based discussion forums, and so on) provides rich and stable support for complex work and interpersonal interactions between developers who rarely if ever see each other “

- High openness to experience -> less assumption of bad faith of colleague’s part.

- “ With experience, members of distributed groups learn to communicate frequently (Jarvenpaa and Leidner 1998), start tasks promptly because of time delays (Iacono and Weisband 1997), disclose personal information (Moore et al. 1999) and explicitly acknowledge receiving messages (Cramton 2001). In essence, experienced tele-workers learn effective norms and routines to be productive in this specific context. ”

- “feeling close reduces the uncertainty and ambiguity of working at a distance and improves at least two of the three dimensions of group effectiveness: (1) capability to work together in the future; and (2) growth and well-being of team members”

- Having a co-located co-worker visit another site helps your relationship with people at that site, even if you don’t visit yourself.

- Too much closeness leads to negative feelings, such as worries about surveillance.

https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/c2c0/1cbfa5796a273aa5396472eb3582e3496b4c.pdf

When does the medium matter? Knowledge-building experiences

and opportunities in decision-making teams

Bradley J. Alge,a,* Carolyn Wiethoff,b and Howard J. Kleinc

- “t media differences existed for teams lacking a history, with face-to-face teams exhibiting higher openness/trust and information sharing than computer-mediated teams. However, computer-mediated teams with a history were able to eliminate these differences. These findings did not extend to team-member exchange (TMX). Although face-to-face teams exhibited higher TMX compared to computer-mediated teams, the interaction of temporal scope and communication media was not significant. In addition, openness/trust and TMX were positively associated with decision-making effectiveness when task interdependence was high, but were unrelated to decision-making effectiveness when task interdependence was low”

- N = 198 undergrads

note y axis

https://www.emeraldinsight.com/doi/abs/10.1108/eb022856?journalCode=ijcma

SUBGROUP DYNAMICS IN INTERNATIONALLY DISTRIBUTED TEAMS: ETHNOCENTRISM OR CROSS-NATIONAL LEARNING? Catherine Durnell Cramton and Pamela J. Hinds

2005

- “There is,

- however, increasing evidence that internationally distributed teams are prone

- to subgroup dynamics characterized by an us-verses-them attitude across sites

- (Armstrong & Cole, 1995; Cramton, 2001; Hinds & Bailey, 2003

- “

- see Gibson & Cohen, 2003; Hinds & Kiesler, 2002

- Diversity isn’t bad, it’s when multiple traits are correlated that you get fault lines

- “Merely becoming aware of the presence of subgroups is adequate to trigger ingroup-outgroup dynamics”

- “t ethnocentrism is reduced under conditions of contact between groups of equal status that are pursuing common goals with institutional or social support”

- Trying to erase team differences costs you the ability to learn from teams

- “Under certain conditions, people can recognize the positive qualities of their own group as well as other groups, constituting what we call an attitude of mutual positive distinctiveness”

- Shared goal == good

- “We conclude that motivation to engage across differences is reduced when groups have unequal status”

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/875697281704800303

Barriers to Tacit Knowledge Sharing in Geographically Dispersed Project Teams in Oil and Gas Projects

Olugbenga Jide Olaniran

- Oh, this is a pitch for delphi

https://www.entrepreneur.com/article/243579

Why This Startup Won't Let the Team Work From Home

Randy Frisch, CEO of Uberflip

- “Our dependence on instant messaging and shorthand updates have decreased our likelihood to brainstorm, opting for a quick WTF or LOL, rather than an attempt to build off a crazy idea.”

- Marissa Mayer: ““People are more productive when they’re alone, but they’re more collaborative and innovative when they’re together. Some of the best ideas come from pulling two different ideas together.””

https://open.buffer.com/remote-team-meetups/

Remote Team Meetups: Here’s What Works For Us

Stephanie Lee

https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=17021655

- Need to be remote-first

AskAManager.org

- Vague missing interactions

https://www.askamanager.org/2015/07/how-to-make-telecommuting-work-for-your-team.html

- Missing collaborative learning

- Nuances get missed

- People don’t believe you’re working because they can’t see you

- “Can’t have remote work and flexible schedule”

- Need ways to replicate social experience

COMMUNICATION, TEAM PERFORMANCE, AND THE INDIVIDUAL: BRIDGING TECHNICAL DEPENDENCIES.

Patrick Wagstrom

James D. Herbsleb

Kathleen M Carley

- Can’t replicate “watercooler experience”

- Need childcare when WFH

- Good to schedule regular meetings

Quora

https://www.quora.com/Digital-Nomads-Can-a-team-manager-work-remotely

- Proper onboarding is essential

- Have regular syncs

- So definitely you can work remotely, the main challenges to overcome are:

- A feeling of separation

- Communication

- Productivity and consistency of work

https://www.quora.com/In-your-experience-what-are-the-most-difficult-things-about-working-remotely

- Easy to lose focus

- Feel disconnected from others/lonely

- People don’t believe you’re working

- Easy to get sucked into working too much

https://www.quora.com/What-are-the-pros-and-cons-of-remote-working-Working-a-job-from-your-home

- Pros:

- no commute

- No control over work environment

- Flexible hours

- Cons:

- Lonely

How do virtual teams process information? A literature review and implications for management

Petru L. Curs¸eu, Rene´ Schalk and Inge Wesse

- “Virtual teams are better in exchanging information and in overcoming information biases. However, they encounter problems in using and integrating information. A greater pool of knowledge leads to higher memory interference in virtual teams. Nevertheless, in virtual teams, processes such as planning and coordination, are less effective and the emergence of trust and cohesion is more difficult to achieve. These opposing effects limit the potential of better knowledge integration in virtual teams.”

- “the development of trust, cohesion and a strong team identity is one of the most difficult challenges for managers of virtual teams. “

- “Especially in the initial phases of the team project, meeting face-to-face will let the team members get acquainted with each other. Direct contact is essential for the development of trust and cohesion”

http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.93.9086&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Virtual Teams: What Do We Know and Where Do

We Go From Here?

Luis L. Martins∗

Georgia Institute of Technology, College of Management, 800 West Peachtree Street NW,

Atlanta, GA 30332-0520, USA

Lucy L. Gilson

Department of Management, School of Business, University of Connecticut, 2100 Hillside Road,

Unit 1041, Storrs, CT 06269-1041, USA

M. Travis Maynard

Department of Management, School of Business, University of Connecticut, 2100 Hillside Road,

Unit 1041, Storrs, CT 06269-1041, USA

2004

- “ researchers have noted the tendency of VTs to possess a shorter lifecycle as compared to face-to-face teams”

- “thee number of ideas generated in VTs has been found to increase with group size, which contrasts with results found in face-to-face groups”

- “, the addition of video resources results in significant improvements to the quality of a team’s decisions (Baker, 2002)”

- “compared to men, women in VTs perceived their teams as more inclusive and supportive, and were more satisfied. Also, in a study of e-mail communication among knowledge workers from North America, Asia, and Europe, Gefen and Straub (1997) found that women viewed e-mail as having greater usefulness, but found no gender differences in levels of usage. Bhappu, Griffith and Northcraft (1997) examined the effects of communication dynamics and media in diverse groups, and found that individuals in face-to-face groups paid more attention to in-group/out-group differences in terms of gender than those in VTs.”

- “found that collocated teams reported a significantly lower number of difficulties with various aspects of project management (such as keeping on schedule and staying on budget) than did virtual or global teams”

- “Several studies have demonstrated that participation levels become more equalized in VTs than in face-to-face teams (Bikson & Eveland, 1990; Kiesler, Siegel & McGuire, 1984; Straus, 1996; Zigurs, Poole & DeSanctis, 1988). The most commonly cited reason for this is the reduction in status differences resulting from diminished social cues”

- “or by team members compared to interactions within face-to-face contexts. In particular, Siegel et al. (1986) found that uninhibited behavior such as swearing, insults, and name-calling was significantly more likely in CMC groups than in face-to-face groups.” This is worse in men.

- “In general, lower levels of satisfaction are reported in VTs than in face-to-face teams (Jessup & Tansik, 1991; Straus, 1996; Thompson & Coovert, 2002; Warkentin et al., 1997)”

- “Finally, satisfaction in VTs appears to be affected by a team’s gender composition. In particular, all-female VTs tend to report higher levels of satisfaction than all-male VTs”

- “For negotiation and intellective tasks, face-to-face teams have been found to perform significantly better that CMC teams, whereas there were no differences found on decision-making tasks (Hollingshead et al., 1993). “

- “A type of task in which CMC groups seem to outperform face-to-face groups is brainstorming and idea-generation because there is no interruption from other group members, in effect allowing all members to “talk” at the same time. “

https://sci-hub.tw/10.1287/orsc.10.6.791

Communication and Trust in Global Virtual Teams

Sirkka L. Jarvenpaa, Dorothy E. Leidner

- “global virtual teams may experience a form of “swift” trust, but such trust appears to be very fragile and temporal”

- Then i stopped reading

https://pubsonline.informs.org/doi/10.1287/orsc.1090.0434

Go (Con)figure: Subgroups, Imbalance, and Isolates in Geographically Dispersed Teams

Michael Boyer O'Leary, Mark Mortensen

2009

- “we find that the social categorization in teams with geographically based subgroups (defined as two or more members per site) triggers significantly weaker identification with the team, less effective transactive memory, more conflict, and more coordination problems.”

- “imbalance in the size of subgroups (i.e., the uneven distribution of members across sites) invokes a competitive, coalitional mentality that exacerbates these effects; subgroups with a numerical minority of team members report significantly poorer scores on identification, transactive memory, conflict, and coordination problems. In contrast, teams with geographically isolated members (i.e., members who have no teammates at their site) have better scores on these same four outcomes than both balanced and imbalanced configurations.”

Virtual teams that Work

Gibson and Somebody

- For virtual teams to perform well, three enabling conditions need to be established:

- “Shared understanding is the degree of cognitive overlap and commonality in beliefs, expectations, and perceptions about a given target. “

- “Integration is the process of establishing ways in which the parts of an organization can work together to create value, develop products, or deliver services. “

- “ integration refers to organizational structures and systems, while shared understanding refers to people’s thoughts.”

- Mutual trust (or collective trust) is a shared psychological state characterized by an acceptance of vulnerability based on expectations of intentions or

- behaviors of others within the team

- Chapter 2: Knowledge Sharing and Shared Understanding in Virtual Teams

Pamela J. Hinds, Suzanne P. Weisband - “ In teams without a common understanding, team members are more likely to hedge their bets against the errors anticipated from others on the team, thus duplicating efforts and increasing the likelihood of rework.”

- “A common occurrence on teams is that members think they have come to agreement, but the agreement they believe they have reached is viewed differently by different team members”

- “shared understanding among team members has these benefits: • Enables people to predict the behaviors of team members • Facilitates efficient use of resources and effort • Reduces implementation problems and errors • Increases satisfaction and motivation of team members • Reduces frustration and conflict among team members”

- Need an understanding of both the task and the process

- “telephone may be better than text-based systems for detecting and resolving misunderstandings.”

- “Weisband (forthcoming) found that teams that shared information about where they were and what they were doing performed better than teams that did not share this information”

- Site visits better than off-site retreats

- Chapter 3: Managing the Global New Product Development Network A Sense-Making Perspective

Susan Albers Mohrman, Janice A. Klein, David Finegold

- “Sense making in the new product development system is by necessity virtual. It occurs simultaneously within and across different levels and elements of the organizational system. “

- This chapter feels buzzwordy as hell and I’m going to skip it

- Chapter 4: Building Trust: Effective Multicultural Communication Processes in Virtual Teams

Cristina B. Gibson, Jennifer A. Manuel

- “Collective trust is a crucial element of virtual team functioning. “

- “collective trust can be defined as a shared psychological state in a team that is characterized by an acceptance of vulnerability based on expectations of intentions or behaviors of others within the team “

- “This larger study began in July 1999 and had two phases: in-depth qualitative case analysis with two different virtual teams from each of eight organizations and a comprehensive quantitative survey that will be administered in each firm and analyzed as to statistical predictors of virtual team effectiveness.”

- On virtual teams “ trust is harder to identify and develop, yet may be even more critical, because the virtual context often renders other forms of social control and psychological safety less effective or feasible. “

- “Some controls actually appear to signal the absence of trust and therefore can hamper its emergence. Institutional controls can also undermine trust when legal mechanisms give rise to rigidity in response to conflict and substitute high levels of formalization for more flexible conflict management (Sitkin and Bies, 1994).”

- “interdependence is also critical in establishing trust in virtual teams.”

- Compliments build trust

- Active listening

- Chapter 8: Exploring Emerging Leadership in Virtual Teams Kristi Lewis Tyran, Craig K. Tyran, Morgan Shepherd

- “A leader is said to emerge in a team when the team as a whole reaches a consensus that they perceive the emergent leader to be their leader”

- “ We found agreement among team members that leaders emerged in nine of the thirteen virtual teams participating in our study. “

- “For traditional teams, trust in a leader’s ability to facilitate team task and relationship interaction effectively has been found to be a critical factor in achieving the consensus necessary for a leader to emerge”

- Types of trust:

- Can do the tasks to achieve the goal

- Altruism

- Friendship

- Leaders were more trusted, especially in task competence

- May be harder to emerge as a leader in virtual teams, in part due to difficulty building trust

- Leaders sent more messages than average but not necessarily the most messages

- “virtual team performance was not clearly related to emergent leadership within the team”

- This seems useless

- Chapter 10: Overcoming Barriers to Information Sharing in Virtual Teams, Catherine Durnell Cramton, Kara L. Orvis

- Skipping the description of problems, assuming it’s similar to Cramton’s other work

- Recommendations:

- “Establish procedures for information sharing within the virtual team. It may be helpful for leaders to distinguish among task, social, and contextual information and to design procedures appropriate to each type of information. For example, task-related information may be best shared at a weekly dial-in conference call in which representatives at each location are guaranteed airtime. It probably is a good idea to designate a facilitator for such conference calls so that time is managed, focus is maintained, and new information is made salient to all.”

- Weekly calls include a few moments where everyone says how they are. I think this is incorrect and it makes me doubt their other suggestions. It will chew up a lot of time, people won’t listen, and isn’t enough time to actually share anything relevant.

- Site Visits

- Longer time frames

- Awww, they’re worrying about the cost of phone calls. So cute.

- “Build the virtual team’s social identity”

- Chapter 14: Influence and Political Processes in Virtual Teams by Efrat Elron, Eran Vigoda

- “ Our study relied on ten semistructured interviews with members of virtual teams” Two companies based in US and Canada, with lots of subsidiaries.

- “We have witnessed a rapid growth in studies that developed well-grounded models and theories of influence and politics in organizations (Bacharach and Lawler, 1980; Gandz and Murray, 1980; Ferris and Kacmar, 1992; Kipnis, Schmidt, and Wilkinson, 1980; Mintzberg, 1983; Pfeffer, 1992; Yukl and Falbe, 1990)”

- “ People in teams that rely heavily on e-mail are therefore more careful with writing than speaking because of the permanency effect of the written word. Thus, political behavior takes on a more careful and covert form when documented.”

- Requests to take off-topic discussions offline curtail political behavior

- “ Noted one participant, “Virtual teams are task oriented. You do not have enough chances to read and understand this politics, if it’s there at all. In fact, I don’t feel that I actually have enough opportunities to be exposed to such activities in my virtual team. We don’t have that much time left for politics; we need to work.””

- “Many multicultural team participants try to be “on their best behavior” when in contact with members from other cultures because they feel that they are not only private individuals but also representatives of their country and culture. As a result, they tend to use tactics that are more acceptable socially”

- “ In general, these findings indicate that VOP may be significantly lower than operational politics in conventional teams. Members of virtual teams report lower intensities in the use of influence and political behaviors compared with similar activities of conventional face-to-face groups. In addition, the most dominant influence attempts used are rationality, consultation, and assertiveness, which are considered among the most socially acceptable tactics and also the most effective ones (Yukl and Tracey, 1992). The use of less acceptable tactics such as sanctions, exerting pressures and threats, and blocking information was denied by all our interviewees. “

- Okay, I can’t take the seriously after that, skipping the rest

- Chapter 15 Conflict and Virtual Teams Terri L. Griffith, Elizabeth A. Mannix, Margaret A. Neale

- “Media effects is a phrase used to describe all the outcomes that result from the use of a particular communication medium. “

- “practice also suggests that even teams located in the same building may communicate largely by e-mail. In fact, in the organization described in this chapter, all teams spent an equal amount of time working face-to-face on the team task (approximately 13 percent). E-mail use did vary by whether all the members were colocated, but not to a great extent (34 percent of all task communication in colocated teams versus 45.76 percent in distributed teams).”

- “What is technically a conflict about the task, for example, may be taken personally and thus be experienced as relationship conflict.”

- They looked at twenty eight teams on a spectrum of virtualness

- “ We found that virtual teams had greater levels of process conflict than traditional teams, but only when also controlling for the effects of trust. We did not find differences in the levels of task or relationship conflict “

- Difference was only .3 out of 5

- “Neither trust nor team identification is significantly related to the distribution of the team members.”

- “regardless of virtualness, relationship and process conflict have significantly negative effects on performance as rated by the team’s manager. Task conflict, however, does not seem to produce these effects.”

- “trust was higher the more the team communicated using e-mail and the more they worked together face-to-face. “

http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.119.3370&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Situation Invisibility and Attribution in Distributed Collaborations

Catherine Durnell Cramton, Kara L. Orvis, Jeanne M. Wilson

2007

- Fundamental attribution error again

https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2004-00215-011

Chapter 11: Leadership in Virtual Teams:

Zaccaro, S. J., Ardison, S. D., & Orvis, K. L. (2004)

- “Zaccaro, Rittman, and Marks (2001) argued that leaders contribute to team effectiveness by influencing five team processes: motivational, affective, cognitive, coordination, and boundary spanning.”

- Trust is the expectation that others will behave as you expect = ability to predict others’ behavior

- “Team effectiveness is grounded in members being motivated to work hard on behalf of the team. “ that seems incomplete at best

- “, team members are more likely to contribute more of their individual efforts to collective action when they trust one another”

- “trust, particularly knowledgebased and identification-based trust, evolves from a long period of face-to-face interactions”

- “t teams with high levels of initial trust devoted almost half of their early communications during the first 2 weeks of the teams’ existence to discussions of their families, hobbies, and weekend social activities...such communications were not sufficient to maintain trust.”

- “trust in temporary teams develops when team members have clearly defined roles with specified and accurate behavioral expectations. “

- “When virtual teams form with members having strong professional identities, then swift trust can emerge from stable role expectations and subsequent actions are likely to confirm these expectations,strengthening team trust.”

- “effective team coordination depends upon the emergence of a shared mental model”

- Skipping the stuff on crampton 2001 since I’ve read the source

- “team leaders need to help their teams set performance objectives that are aligned with the strategic requirements operating in the team environment”

Aaron Gertler @ 2020-05-22T03:18 (+2)

This post was awarded an EA Forum Prize; see the prize announcement for more details.

My notes on what I liked about the post, from the announcement:

Elizabeth’s artfully-written literature review covers a topic of practical import to many EA organizations: does remote work… work? And if so, how do we maximize its potential?

I won’t go into detail on her findings (read the review!), but I’ll point out some features of the post that I especially liked:

- A “highlights and embellishments” section which shows the author’s key takeaways from the dozens of isolated facts presented in the full review

- A “sources of difficulty” section which points out weaknesses in the available data

- The occasional use of personal anecdotes to illustrate points (I appreciate the way that anecdotes aid memory, as long as they’re used to support solid research)

- The author’s inclusion of a PDF link (Cramton 2016) that they obtained directly from another researcher, giving readers access to information they might not have been able to find themselves