Rewilding Is Extremely Bad

By Bentham's Bulldog @ 2025-11-18T17:44 (+8)

Crosspost of my blog article.

Rewilding is the process of converting fairly substantial tracts of industrial land back into nature. What once was farmland or a logging area returns to its natural state. The consensus among most people tends to be that it’s a pretty uncontroversially good idea. This consensus, I think, is badly wrong. Rewilding is extremely immoral—worse than almost any other thing we do—and we should refrain from it barring exceptional circumstances.

What’s so bad about rewilding? The basic case against is that it majorly increases wild animal suffering. If we assume wild animals are spread uniformly across Earth’s land, then each square mile of land contains 1,754-17,540 mammals, 1,754-1,754,000 reptiles, and 1,754-1,754,000 amphibians.

Where things get really extreme is with insects.

On average, a square foot of land contains about 750 insects. This means that if you rewild a square mile of land, over the course of a year, 20.9 billion additional insect life-years will be lived. If we assume that each insect lives two weeks—a fairly reasonable estimate—then a mile of rewilded land produces about 585,480,000,000 (five-hundred-eighty-five-billion-four-hundred-eighty-million) extra insect lives and deaths annually.

Let’s assume conservatively that half that many insects would have lived and died on the land if it wasn’t rewilded and that insects suffer 1% as intensely as people (which I think is an underestimate in expectation). Then we get the result that rewilding a single square mile of land produces about as much pain as that of nearly 2,927,400,000 extra human deaths. And if we count soil animals, then things get worse, in expectation, by orders of magnitude. Each square mile of land rewilded is a very serious moral atrocity. There could very well be more suffering in a thousand miles of rewilded land over the course of a few years than all suffering that’s existed so far in human history.

Now, it would be one thing if this suffering was compensated by a similar increase in well-being. But it’s not. As I’ve argued at length, nature contains vastly more suffering than well-being. Most animals live only a few days or weeks and die painfully. They have nowhere near enough well-being over the course of their life to outweigh their extremely painful deaths.

If you lived just a week, and then starved to death or got eaten alive, your life wouldn’t have been worth living. But this is the fate of almost all animals who have ever lived. Nearly all of them have very short lives that culminate in a painful death. A few fleeting moments of joy aren’t enough to compensate for the intense suffering at their end of life.

And while there might be deontological prohibitions against destroying nature, these certainly don’t justify bringing nature back. There is no reason to bring nature back, forcing countless beings to live a brief life of misery, terror, and agony. Compassion demands better. If there are deontic prohibitions in this area, then they certainly militate against forcing countless beings to be eaten alive and starve to death.

Now, what defenses are there of rewilding? One is that nature is very pretty. Humans benefit from having nature nearby. These benefits are small and uncertain. They’re completely swamped by the impact on wild animals.

Others suggest that nature is a good thing intrinsically. I find this perspective baffling; if nearly every creature in nature is running for its life, very soon to be dead, likely to starve or be eaten alive by the end of the week, then nature isn’t worth preserving. It’s extremely implausible that nature has intrinsic value—if you try to make the view precise, it collapses completely. More importantly, even if nature has some intrinsic value, it doesn’t have enough to justify causing more suffering than has ever existed in human history, every few years, in relatively small plots of land.

Now, maybe you just don’t care about the interests of wild animals. But this is a fairly baffling moral perspective—one that cares deeply about nature, but doesn’t care one lick for the beings in nature. If we should care about an abstraction like nature, then we should care about the real sentient beings that live in nature. An abstraction like nature never feels anything. An individual deer, ripped limb from limb by lions, does. This view strikes me as like caring about a country but not caring about any of the people in the country.

And it is very difficult to see why it is that beings in nature wouldn’t matter. Surely humans mattered a few hundred thousand years ago, even when we were part of nature. So merely being part of the natural ecosystem doesn’t strip one of moral worth. But then it’s hard to see what about wild animals would make them not deserving of moral consideration. One can’t say that it’s being part of nature and being unintelligent (as wild animals are) because that would imply that mentally disabled people didn’t matter before the dawn of civilization (when they were part of hunter-gatherer societies).

Come to think of it, it’s not at all clear that there’s a precise definition of being part of nature—arguments against caring about wild animals, then, inevitably turn into arguments against caring about animals at all. They’d then imply it would be fine to torture dogs for trivial reasons.

And as I’ve argued many times, it’s bad to suffer because of how suffering feels, not extrinsic characteristics like whether one is a wild animal. The fact that wild animals experience many thousands of times more suffering than all humans combined, in expectation, makes their suffering an urgent priority.

Now, the only serious argument for rewilding (if one grants that wild animals mostly live bad lives, which I think there is a very powerful case for) is that doing so can reduce existential threats. The argument goes: rewilding reduces existential risks by improving environmental quality and reducing global warming. Because the future could be so enormous, this outweighs the harms to wild animals in the present.

I find much about this argument extremely dubious.

- The people who make it generally would not accept this logic in other domains. Virtually no one would support torturing billions of people if doing so would reduce existential threats by .00000000000000001%. We don’t normally think it’s worth causing hideous, unfathomable quantities of suffering to maybe reduce existential risks by a tiny amount.

Rewilding has no serious impact on existential risk. The primary existential risks it could reduce are from biodiversity and climate change. But neither of these are major existential risks. John Halstead, after producing the most detailed report on climate existential risks done ever, guessed the odds of climate change existential risk were way below .1%—there’s just no coherent mechanism by which it would spell doom, the world has survived past periods of significant warming without facing catastrophic collapse, and the impact of climate change on food production will be largely insignificant. And rewilding has relatively limited impact on climate change.

The scenario for climate change causing extinction generally involves refugee crises triggering a nuclear war. This is very implausible; the places where climate change is likely to cause extra wars are mostly in Africa, which has no great powers. The overall impact on wars is likely to be fairly negligible, as the studies Halstead reviews find, and there’s no plausible mechanism by which such conflicts would go nuclear. Even the IPCC found that there’s little evidence for climate change causing interstate wars—rather than civil wars—which are the only kind that could plausibly go nuclear.

Biodiversity loss as an existential risk is even more unlikely—you can read Halstead’s report for more detail but many places have lost nearly all their biodiversity without facing any societal crisis. When you account for most species loss being on island nations, biodiversity isn’t even declining by that much. And even a collapse of biodiversity wouldn’t endanger food sources; pollinators only are responsible for about 5% of crop yields, and the rest of biodiversity contributes little to food production. There is, of course, no coherent way that rewilding a bit would have any effect on the kind of biodiversity crisis that would kill off the pollinators.

When you ask those who think that biodiversity loss will cause extinction how it would do so, you get one of two explanations. The first is pseudoscience, like that the loss of biodiversity will lead to us running out of Oxygen. This is laughable as Oxygen cycling works on scales of millennia and the net effect from biodiversity loss on Oxygen is likely to be very minor—a textbook on the subject recounts “changes in atmospheric oxygen concentration, although measurable, will be trivial until coupled, global-scale geologic/ biological processes conspire to change them. This would likely take millions of years.”

The other way of arguing involves vague innuendo about tipping points and the like. It involves tossing about lots of apocalyptic words (brink, tipping point, and so on), but few specific scenarios. These risks are not generally taken seriously by climate scientists, but instead promulgated by activists. In light of the poor track record of such claims, and the fact that humanity has survived fine despite exterminating most European forests (contra claims of existential tipping points), they should not be taken very seriously unless backed up by strong evidence, which they never are. And in any case, rewilding would have a minuscule impact on the global climate, so if we’re otherwise doomed, rewilding is extremely unlikely to save us.

- Given that existential risks affected by rewilding are so minor, they could very well be outweighed by the opposite risks—the risks caused by rewilding. Rewilded areas could introduce new diseases that pose existential risks, for example, or the economic delay could result in America losing a technological arms race to China. Given how low the risks of extinction are in the other direction, these could be more significant.

- In my view a much bigger risk from rewilding is that we’ll get in the habit of rewilding, and then spread nature across the universe. This could be the cause of many terraformed planets—and utterly incomprehensible quantities of suffering. By delivering successful rewilding, a pro-nature coalition might be built, which would spread incomprehensible amounts of suffering to the stars. This could be an S-risk—a risk of astronomical suffering, on the order of existential risks in moral horror. And while I expect most future people to be digital, the impact on spreading wild animal suffering to the stars seems more significant than rewilding’s trivial impacts on existential risks. The values we have today will influence what we do in the future; if they are environmentalist pro-rewilding values, the future may be hell for countless quintillion beings.

As Bostrom has argued, we might currently be in a simulation. If we are, then our actions potentially are mirrored across all simulated worlds. If so, then rewilding doesn’t produce astronomical suffering just in our universe, but in all universes. Thus, as Brian Tomasik has argued, the simulation argument weakens the case for caring almost exclusively about the future, which is the only sound basis for prioritizing the minuscule possible existential risk reduction over the enormous present suffering caused by rewilding. A tiny reduction in the risks of the 8 billion people alive today is paltry compared to the impact on the quintillions of suffering wild animals.

It would be one thing if we were comparing major impacts on existential risks to major suffering reductions. But we’re not. We’re comparing tiny and highly uncertain in terms of their overall sign impacts on existential risks to very sizeable increases in suffering. In such a choice, given moral uncertainty, one should refrain from causing huge amounts of extreme suffering.

Now, don’t get me wrong: I’m pretty Longtermist. I think the most important thing to do today is make the future go well. But I’m not so Longtermist that I’m willing to cause extreme suffering to countless beings for a wildly unclear—and certainly tiny—impact on existential risks.

All of this is to say that if you are a consequentialist, you should be very opposed to rewilding. It causes countless innocent beings to suffer horribly. Because nearly all wild animals live short lives of intense suffering, rewilding is a major moral catastrophe—just about the worst thing we could do collectively.

Tristan Katz @ 2025-11-18T19:46 (+56)

I think, by cross-posting this here, you're largely preaching to the choir - and I'm no exception. I agree that rewilding is an ethically questionable practice and that we should focus a lot (or most) of our attention on invertebrates. I especially like the argument against viewing conservation as necessary for the future survival of life - this is so common and poorly justified.

That said, I think this post could do a much better job of steelmanning the opposition. The assumption that welfare in nature is net-negative is far from obvious: good arguments to the contrary have been given here. There's also this article, although I think its assumptions are more questionable. To illustrate, consider:

- The most numerous wild animals, which your argument focuses on, might not be sentient at all. The jury is still out.

- If they are sentient, they might not be so during that first week of life when they're most likely to die.

- Even if they were, since none of us have lived a week and then died as an insect, we should be careful about assuming what that experience is like: doing things and seeing the world for the first time might be positive experiences (think about how a toddler seems to enjoy many very ordinary things); they might suffer less than humans when dying; but even humans often report numbness or even positive near-death experiences (this is all explained better in the previously linked post).

- Even if their deaths are very painful, they're likely to occur over minutes, whereas there are 168 hours in a week. That this isn't worth it is non-obvious. While we often say that we wouldn't trade a painful experience for something good, we normally say that while expecting to keep living. If we knew we would die in a week, we might be willing to endure a few minutes of pain for another week of precious life.

Note, I'm not saying we can't or shouldn't make such judgements. I'm just saying we shouldn't be quick to make them, especially when we're talking about whether thousands of other animals should live or not. We should steelman the view that wild animals have good lives.

Ben Stevenson @ 2025-11-19T12:59 (+6)

Another relevant article is this RP report, which argues "Knowing a group of organisms produce many offspring, have high mortality rates, small body size and are short-lived is not sufficient to determine that their lives are a net negative (or positive)".

NickLaing @ 2025-11-19T18:09 (+3)

Amazing comment appreciate this a lot. I think though its not quite "preaching to the choir" though given the karma hit the post has taken...

Tristan Katz @ 2025-11-19T19:18 (+1)

Yea, I'm a little surprised (based on the interactions I've had with EAs about the topic). Would be nice if more people commented, to see whether it's real disagreement or just a desire for more rigor.

NickLaing @ 2025-11-18T19:40 (+13)

i disagree with this and think rewilding uf probably good because i think wild animals overall have net positive lives. this is because

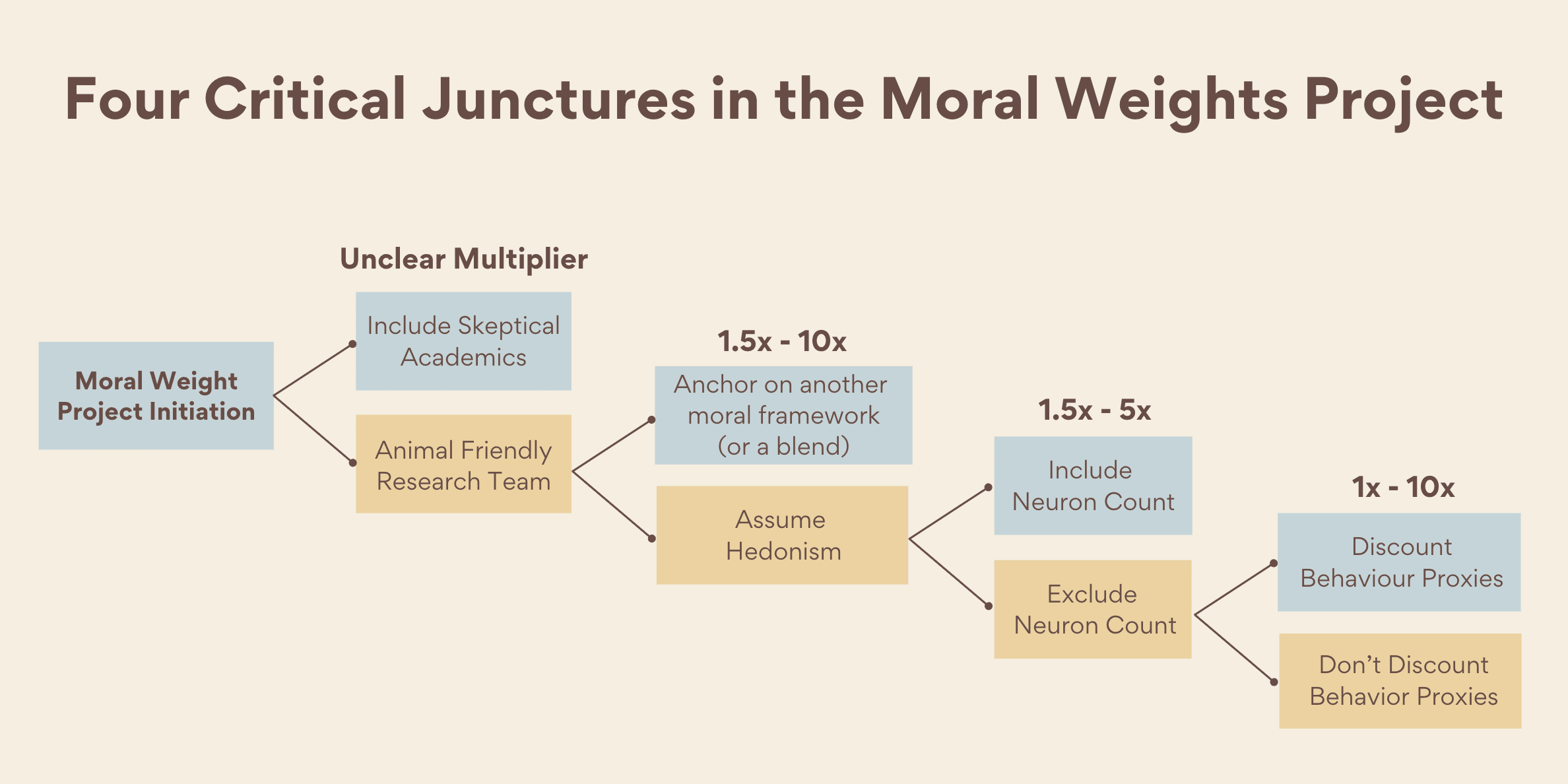

- i don't believe very small animals feel pain, and if they do my best guess would be it would be thousands to millions orders of magnitude less pain than larger animals. After looking into Rethink's methodology, i feel they grossly overestimate percentage chances of small animal sentience, and I'm personally not compelled by associating negative stimuli responses with meaningful feelings of pain. Bob Fischer writes a great counterargument to my claim here

I'm not very confident of this though so see no.2...

- Even if small (and small ish) animals did feel pain I think even very short lives of the small majority prey animals can be net positive, mostly because i don't buy big negative welfare multipliers around the time of death. i believe you could have a net positive one days life as an ant, even if you got chomped to death by a bigger ant at the end of the day.

- i think immature animals which die very young may have much less capacity for pain (and pleasure) than their adult counterparts. So in my books one long decent life for a prey animal which lived a longish life, might outweigh potential suffering of thousands of immature creatures that died young (if I'm wrong on number 2)

- i think larger wild animals (both prey and predator) have

greatdecent lives and am unconvinced that rampant fear and disease makes these lives negative. So if smaller animals were indeed welfare-irrelevant then i think bigger ones could carry the positive welfare calculation.

I think there is a decent case for wild animals having net negative lives, but calling it "very powerful" like you do is an overshoot, more because of high cluelessness than my amateur above arguments.

But yes if net wild animal welfare was negative then i agree ewilding would be bad.

David Mathers🔸 @ 2025-11-19T11:16 (+17)

"i don't believe very small animals feel pain, and if they do my best guess would be it would be thousands to millions orders of magnitude less pain than larger animals."

I'll repeat what regular readers of the forum are bored of me saying about this. As a philosophy of consciousness PhD, I barely ever heard the idea that small animals are conscious, but their experiences are way less intense. At most, it might be a consequence of integrated information theory, but not one I ever saw discussed and most people in the field don't endorse that one theory anyway. I cannot think of any other theory which implies this, or any philosophy of mind reason to think it is so. It seems very suspiciously like it is just something EAs say to avoid commitments to prioritizing tiny animals that seem a bit mad. Even if we take seriously the feeling that those commitments are a bit mad, there are any number of reasons that could be true apart from "small conscious brains have proportionally less intense experiences than large conscious brains." The whole idea also smacks to me of the idea that pain is literally a substance, like water or sand that the brain somehow "makes" using neurons as an ingredient, in the way that combining two chemicals might make a third via a reaction, and how much of the product you get out depends on how much you put in. On mind-body dualist views this picture might make some kind of surface sense, though it'll get a bit complicated once you start thinking about the possibility of conscious aliens without neurons. But on more popular physicalist views of consciousness, this picture is just wrong: conscious pain is not stuff that the brain makes.

Nor does it particularly seem "commonsense" to me. A dog has a somewhat smaller brain than a human, but I don't think most people think that their dog CAN feel pain, but it feels somewhat less pain than it appears, because it's brain is a bit smaller than a persons. Of course, it could be intensity is the same once you hit a certain brain size no matter how much you then scale up, but it starts to dop off proportionately when you hit a certain level of smallness, but that seems pretty ad hoc.

NickLaing @ 2025-11-21T21:36 (+3)

I don't appreciate the comment "It seems very suspiciously like it is just something EAs say to avoid commitments to prioritizing tiny animals that seem a bit mad." Why not instead that assume people like me are actually thinking and reasoning in good faith, and make objective arguments, rather than deriding them in the middle of your otherwise good argument. If we were just intellectually dodging, I doubt we would be here on the forum trying to discuss and figure this thing out...

i could be wrong, but i think my kind of response here probably is common sense-ish (right or wrong). if you polled 100 in people on the street "assuming worms feel pain at all, do you think worms feel a lot less pain than humans?", i think the response would be an overwhelming yes.

The dog question is a bit of a strawman because that's not the question being discussed, but i would guess most people would believe that their dog feels less pain than they do (or it appears) as well, although the response here i agree would be quite different than the worm question.

I have looked a little at theories of the mind and i must confess i find it hard to get my head around them well. I have seen though that they are many and varied and there seems to be little consensus.

to have a go at explaining my thoughts, I don't think that pain is like a substance, but i do think that the way tiny creatures are likely to experience the world is ways so wildly different from us, that even if there is something like sentience there, experiences for them might be so different to ours (including pain) that their experience, memory and integration of that "pain" (if we can even call out that same word) is likely to be so much smaller/blunted/muffled/different? compared with us (if it can even be compared), even if their responses to painful stimuli are similar ish. Pain responses are often binary-ish options (aversion or naught), but when it comes to felt experience the options are almost endless. I consider my experience growing up as a child, from complete blank to age 3, to to a foggy awareness, to something more concrete now. And what of a fetus before that?

so yes, the statement you readily deride "small conscious brains have proportionally less intense experiences than large conscious brains." makes a decent amount of sense to me as a real possibility.

i could be wrong but this line of reasoning does seem related to integrated information theory (as far as i can tell).

Also i don't at all understand how this comment can be true "pain is not stuff that the brain makes." Without the brain there is no pain - does the the brain not then "make" it with neurons and chemicals? If the neuron/brain does not make the pain then what does make it? something has to make it. Unless there is some sleight of hand here around the word "make"...

Mo Putera @ 2025-11-19T06:23 (+5)

After looking into Rethink's methodology, i feel they grossly overestimate percentage chances of small animal sentience, and I'm not compelled by associating negative stimuli responses with meaningful feelings of pain.

Just wanted to link to your post on this for readers who haven't seen it, as I really appreciated it: Is RP's Moral Weights Project too animal friendly? Four critical junctures

And your flow diagram:

Tristan Katz @ 2025-11-18T20:36 (+4)

Regarding (2), do you think sentience gradually increases, or there's a cutoff? My own memory is of having very intense joy and pain/sadness as a small child, maybe more than now. So while I put less credence in the sentience of young animals, my assumption is that if sentient they could have intense feelings.

I want to push back (3) (larger animals having 'great' lives). I'm not sure if you meant that: but take any pet cat or dog, and then make them hungry, often. Make them cold, make them occasionally very afraid, and give them parasites and untreated injuries. Make them live only 1/4 of their full lifespan. Now even if that's worth living, surely it isn't a 'great' life!

NickLaing @ 2025-11-19T04:56 (+8)

I'm deeply unsure about all of this.

regarding 2 i have no memory before the age of maybe 3 or 4. I'm not sure the analogy with humans is the best, but if we were to use that, then most tiny animals would die before the age of a few month human, not a small child, who i agree can have intense memorable experiences.

good point in the "great" lives claim, I've edited to "decent". again I'm not sure weak pets are the best analogy, they aren't adapted for the wild. to go back to humans, we used to live with not of the cold, parasites and untreated injuries. I think we would have had decent lives while still suffering those problems. A lot worse lives sure, but decent all the same.

Stien @ 2025-11-19T12:16 (+10)

Hi, would you help me interpret your writing style so I can better understand? No (fast) answer expected at all.

To me, this post reads as written with a lot of confidence and urgency, giving a sense of certainty.

Is this a stylistic choice to create engagement (which could either mean increased readership or a discussion aimed at learning)? Or is this because you are completely convinced? Or time pressure or something else?

Thanks for explaining!