Caring about Bugs Isn’t Weird

By Bob Fischer @ 2025-11-23T12:44 (+173)

I’ve spoken with hundreds of entomologists at conferences the world over. While there’s clearly some self-selection (not everyone wants to talk to a philosopher), my experience is consistent: most think it’s reasonable to care about the welfare of insects. Entomologists don’t regard it as the last stop on the crazy train; they don’t worry they’re getting mugged; they don’t think the idea is just utilitarianism run amok. Instead, they see some concern for welfare as stemming from a common-sense commitment to being humane in our dealings with animals.

Let’s be clear: they embrace “some concern,” not “bugs have rights.” Entomologists generally believe it’s important to do invasive studies on insects, to manage their populations, to kill them to document their diversity. But given the choice between an aversive and a non-aversive way of euthanizing insects, most prefer the latter. Given the choice between killing fewer insects and more, most prefer fewer. They don’t want to end good lives unnecessarily; they don’t want to cause gratuitous suffering.

It wasn’t always this way. But the science of sentience is evolving; attitudes are evolving too. These people work with insects every day; they constantly face choices about how to catch insects, how to raise them, how to study them, how to end them. Questions about insect monitoring, use, and management are top of mind. Questions about how to treat insects, therefore, are hard to avoid.

So, the welfare of insects is not just—or even primarily—a “weird EA thing.” The people who work with these animals think they’re worth some care. Lots of ordinary people do too. And we, who show our concern for suffering through spreadsheets, are one more voice in that chorus.

Let’s be clear again: nothing follows about cause prioritization from the attitudes of entomologists (or anyone else). I'm not saying: “Entomologists sometimes try to be marginally nicer to their insects; so, all the money should go to bugs.” I do not think that all the money should go to bugs. Or even most of the money. Or even most of the animal money. To pick a number somewhat arbitrarily, I might think that, at most, 10% of animal dollars should go to invertebrates in the near-term.

There are several reasons for this. First, my best guess is that organizations working on invertebrates aren’t ready to absorb $25M–$30M (which is ~10% of total animal movement spending (though we could absorb more than we’ve got, and some orgs more than others). Second, I don’t think other animal organizations should pivot away from effective interventions just because there’s something else that could, in principle, be even more cost-effective: in practice, they won’t be able to do that new thing cost-effectively for a long time. We care about doing the most good per dollar, not working on the problem that, abstractly described, sounds most important in expectation. Third, it’s easy for an org to think it’s helping when it’s hurting: we know so little about how to help that some caution is warranted. I don’t just want to do good in expectation: I want to do good. And finally, I want a thriving ecosystem of people who are committed to working on the world's most pressing problems. A thriving ecosystem is bound to be a diverse one, due to differences in ideology, temperament, and opportunity, among many other things. And given as much, funding shouldn't be narrowly focused on what's of most concern to me; there should be plenty of room for others.

But my point here is not really about the resources that should—or shouldn’t—be directed to insect welfare. Instead, it’s about how we approach the issue. In some of the talks I’ve given on insects, I adapted lines from Will MacAskill: “Insects might count. There are a lot of them. And we can make their lives better.” While I stand by those basic points, I regret implying that the case for caring about insect welfare is, ultimately, a wild gambit, where the sheer numbers make the conclusion irresistible.

I do not care about insects because there are a lot of them. Entomologists don’t either. My conversations suggest that they care—when they do—because they’ve sat for countless hours watching ants, or they’ve fed oranges to Madagascar hissing cockroaches (which the roaches love), or they’ve watched a beetle struggling in a kill jar. And they didn’t just watch; they looked.

We should all look more closely—to the point that, if we see suffering, we need to look away. I want to be the kind of person who flinches at another's pain. Even an insect's.

Michael St Jules 🔸 @ 2025-11-24T08:06 (+24)

Great post! :)

Third, it’s easy for an org to think it’s helping when it’s hurting: we know so little about how to help that some caution is warranted. I don’t just want to do good in expectation: I want to do good.

FWIW, I think this would count against most animal interventions targeting vertebrates (welfare reforms, reductions in production), and possibly lead to paralysis pretty generally, and not just for animal advocates.

If we give extra weight to net harm over net benefits compared to inaction, as in typical difference-making views, I think most animal interventions targeting vertebrates will look worse than doing nothing, considering only the effects on Earth or in the next 20 years, say. This is because:

- there are possibly far larger effects on wild invertebrates (even just wild insects and shrimp, but also of course also mites, springtails, nematodes and copepods) through land use change and effects on fishing, and huge net harm is possible through harming them, and

- there's usually at least around as much reason to expect large net harm to wild animals as there is to expect large net benefit to them, and difference-making gives more weight to the former, so it will dominate.

There could be similar stories for the far future and acausally, replacing wild animals on Earth with far future moral patients and aliens. There are also possibilities and effects of which we're totally unaware.

That being said, I suspect typical accounts of difference-making lead to paralysis pretty generally for similar reasons. This isn't just a problem for animal interventions. I discussed this and proposed some alternative accounts here.

Bracketing can also sometimes help. It's an attempt to formalize the idea that when we're clueless about whether some group of moral patients is made better off or worse off, we can just ignore them and focus on those we are clueful about.

NickLaing @ 2025-11-24T11:52 (+4)

I like the idea of bracketing, but i feel like we're never completely clueless when it comes to animal welfare - there's always a "chance" of sentience right? I don't see how it could help here.

Is there then some kinds of probability range threshold we should consider close -to-clueless and bracket out?

Also It's easier for me who is pretty happy right now that insects and anything smaller aren't important in welfare calculations, but if you do give extra weight to harm in calculations, and you do think insects have a non-negligible chance of pain, I agree with MichaelStJules's that's bound to lead to a lot of inaction.

As a side note i think we all want to do good, not just good in expectation, but "good in expectation" is the best we can do with limited knowledge right?

Bob Fischer @ 2025-11-24T12:54 (+14)

Thanks, Nick. A few quick thoughts:

- It's reasonable to think there are important differences between at least some insects and some of the smaller organisms under discussion on the Forum, like nematodes. See, e.g., this new paper by Klein and Barron.

- I don't necessarily want to give extra weight to net harm, as Michael suggested. My primary concern is to avoid getting mugged. Some people think caring about insects already counts as getting mugged. I take that concern seriously, but don't think it carries the day.

- I'm generally skeptical of Forum-style EV maximization, which involves a lot of hastily-built models with outputs that are highly sensitive to speculative inputs. When I push back against EV maximization, I'm really pushing back against EV maximization as practiced around here, not as the in-principle correct account of decision-making under uncertainty. And when I say that I'm into doing good vs. doing good in expectation, that's a way of insisting, "I am not going to let highly contentious debates in decision theory and normative ethics, which we will never settle and on which we will all change our minds a thousand times if we're being intellectually honest, derail me from doing the good that's in front of me." You can disagree with me about whether the "good" in front of me is actually good. But as this post argues, I'm not as far from common sense as some might think.

- FWIW, my general orientation to most of the debates about these kinds of theoretical issues is that they should nudge your thinking but not drive it. What should drive your thinking is just: "Suffering is bad. Do something about it." So, yes, the numbers count. Yes, update your strategy based on the odds of making a difference. Yes, care about the counterfactual and, all else equal, put your efforts in the places that others ignore. But for most people in most circumstances, they should look at their opportunity set, choose the best thing they think they can sweat and bleed over for years, and then get to work. Don't worry too much about whether you've chosen the optimal cause, whether you're vulnerable to complex cluelessness, or whether one of your several stated reasons for action might lead to paralysis, because the consensus on all these issues will change 300 times over the course of a few years.

NickLaing @ 2025-11-24T13:40 (+10)

nice one that's excellent i agree with all of that.

To clarify think a lot of forum EV calculation in the global health space (not necessarily maximization) is pretty reasonable and we don't see the wild swings you speak of.

But yeah naive maximization based on hugely uncertain calculations which might tell us stopping factory farming is good one day, then bad the next - i don't take that seriously.

Vasco Grilo🔸 @ 2025-11-26T20:14 (+5)

Hi Nick.

But yeah naive maximization based on hugely uncertain calculations which might tell us stopping factory farming is good one day, then bad the next - i don't take that seriously.

I wonder whether people are sufficiently thinking at the margin when they make the above criticism. I assume good algorithmic trading models could easily say one should invest more in a company in one day, and less in the next. This does not mean the models are flawed. It could simply mean there is uncertainty about the optimal amount to invest. It would not make sense to frequently shift a large fraction of the resources spent on stopping factory-farming from day to day. However, this does not follow from someone arguing there should be more factory-farming in one day, and less in the next. What follows from a post like mine on the impact of factory-farming accounting for soil animals are tiny shifts in the overall portfolio. I have some related thoughts here.

In addition, I think the takeaway from being very uncertain about whether factory-farming increases or decreases animal welfare is that stopping it is not something that robustly increases welfare. I recommend research on the welfare of soil animals in different biomes over pursuing whatever land use change interventions naively look the most cost-effective.

NickLaing @ 2025-11-27T13:57 (+4)

If we're not something like robustly certain that stopping factory farming increases animal welfare then we're not robustly certain anything increases animal welfare.

Trading can happen second to second. Real work on real issues requires years of planning and many years of carrying out. I don't think its wise to get too distracted mid-action unless there is pretty overwhelming evidence that what you are doing is probably bad, or that there's a waaaaaaaaaaaaaay better thing to do instead. Making "Tiny shifts" in a charity portfolio isn't super practical. Rather when we are fairly confident that there's something better to be done I think we slowly and carefully make a shift. And being "fairly confident" is tricky.

Vasco Grilo🔸 @ 2025-11-27T21:45 (+2)

If we're not something like robustly certain that factory farming increases animal welfare then we're not robustly certain anything increases animal welfare.

I think you meant "stopping factory-farming". I would say research on the welfare of soil animals has a much lower risk of decreasing welfare in expectation.

Trading can happen second to second. Real work on real issues requires years of planning and many years of carrying out.

Here is how I think about this.

Making "Tiny shifts" in a charity portfolio isn't super practical.

I do not know what you mean by this. However, what I meant is that it makes sense to recommend Y over X if Y is more cost-effective at the margin than X, and the recommendation is not expected to change the marginal cost-effectiveness of X and Y much as a result of changes in their funding caused by the recommendation (which I believe applies to my post).

NickLaing @ 2025-11-28T07:42 (+4)

yes i missed the word stopping!

yes we can always do research for sure that's great. I was considering direct work though not including research.

Vasco Grilo🔸 @ 2025-11-28T10:08 (+2)

In terms of direct work, I think interventions with smaller effects on soil animals as a fraction of those on the target beneficiaries have a lower risk of decreasing animal welfare in expectation. For example, I believe cage-free corporate campaigns have a lower risk of decreasing animal welfare in expectation than decreasing the consumption of chicken meat. For my preferred way of comparing welfare across species (where individual welfare per animal-year is proportional to "number of neurons"^0.5), I estimate decreasing the consumption of chicken meat changes the welfare of soil ants, termites, springtails, mites, and nematodes 83.7 k times as much as it increaes the welfare of chickens, whereas I calculate cage-free corporate campaigns change the welfare of such soil animals 1.15 k times as much as they increase the welfare of chickens. On the other hand, in practice, I expect the effects on soil animals to be sufficiently large in both cases for me to be basically agnostic about whether they increase or decrease welfare in expectation.

Vasco Grilo🔸 @ 2025-11-26T19:53 (+6)

Hi Bob.

I don't necessarily want to give extra weight to net harm, as Michael suggested. My primary concern is to avoid getting mugged. Some people think caring about insects already counts as getting mugged. I take that concern seriously, but don't think it carries the day.

Does it make sense to be concerned about being mugged by a probability of sentience of, for example, 1 %, which I would guess is lower than that of nematodes? The risk of death due to driving a car in the United Kingdom (UK) is something like 2.48*10^-7 per 100 km, but people there do not feel mugged by some spending on road safety. I think not considering abundant animals with a probability of sentience of 1 % is more accurately described as neglecting a very serious risk, not as being mugged. I understand your concern is that the probability of sentience of 1 % is not robust, but I believe one should still not neglect it. I see the lack of robustness as a reason for further research.

Michael St Jules 🔸 @ 2025-11-26T23:23 (+9)

My sense is that if you're weighing nematodes, you should also consider things like conscious subsystems or experience sizes that could tell you larger-brained animals have thousands or millions of times more valenced experiences or more valence at a time per individual organism. For example, if a nematode realizes some valence-generating function (or indicator) once with its ~302 neurons, how many times could a chicken brain, with ~200 million neurons, separately realize a similar function? What about a cow brain, with 3 billion neurons?

Taking expected values over those hypotheses and different possible scaling law hypotheses tends, on credences I find plausible, to lead to expected moral weights scaling roughly proportionally with the number of neurons (see the illustration in the conscious subsystems post). But nematodes (and other wild invertebrates) could still matter a lot even on proportional weighing, e.g. as you found here.

Vasco Grilo🔸 @ 2025-11-27T11:56 (+3)

Thanks, Michael.

My sense is that if you're weighing nematodes, you should also consider things like conscious subsystems or experience sizes that could tell you larger-brained animals have thousands or millions of times more valenced experiences or more valence at a time per individual organism.

These numbers are already compatible with individual welfare per animal-year proportional to "number of neurons"^0.5, which has been my speculative best guess. This suggests 1 fully happy human-year has 18.9 k (= 1/(5.28*10^-5)) times as much welfare as 1 fully happy soil-nematode-year.

Taking expected values over those hypotheses and different possible scaling law hypotheses tends, on credences I find plausible, to lead to expected moral weights scaling roughly proportionally with the number of neurons (see the illustration in the conscious subsystems post).

I have also been updating towards a view closer to this. I wonder whether it implies prioritising microorganisms (relatedly). There are 3*10^29 soil archaea and bacteria, 613 M (= 3*10^29/(4.89*10^20)) times as many as soil nematodes.

As a side note, what I do not find reasonable is individual welfare per animal-year being proportional to 2^"number of neurons".

But nematodes (and other wild invertebrates) could still matter a lot even on proportional weighing, e.g. as you found here.

Agreed. In addition to the estimates in that section for the effects on soil animals as a fraction of those on the target beneficiaries, I have some for the total welfare of animal populations. For individual welfare per animal-year proportional to the number of neurons, I estimate the absolute value of the total welfare of soil nematodes is 47.6 times that of humans.

Vasco Grilo🔸 @ 2025-11-27T10:18 (+2)

FWIW, my general orientation to most of the debates about these kinds of theoretical issues is that they should nudge your thinking but not drive it. What should drive your thinking is just: "Suffering is bad. Do something about it." So, yes, the numbers count. Yes, update your strategy based on the odds of making a difference. Yes, care about the counterfactual and, all else equal, put your efforts in the places that others ignore. But for most people in most circumstances, they should look at their opportunity set, choose the best thing they think they can sweat and bleed over for years, and then get to work.

As I just commented, I like this point to understand your general orientation better, but I do not seem to agree with the sentiment about the impact of moral views on cause prioritisation. It makes sense to have 4 years with an impact of 0 throughout a career of 44 years to increase the impact of the remaining 40 years (= 44 - 4) by more than 10 % (= 4/40). In this case, the impact would not be 0 "in most circumstances" (40/44 = 90.9 % > 50 %). So I very much agree with a literal interpretation of the above. However, I feel like it conveys that moral views, and cause prioritisation are less important than what they actually are.

Michael St Jules 🔸 @ 2025-11-24T17:39 (+8)

Ya, bracketing on its own wouldn’t tell you to ignore a potential group of moral patients just because its probability of sentience is very small. The numbers could compensate. It's more that conditional on sentience, we'd have to be clueless about whether they're made better or worse off. And we may often be in this position in practice.

I think you could still want some kind of difference-making view or bounded utility function used with bracketing, so that you can discount extreme overall downsides more than proportionally to their probability, along with extreme upsides. Or do something like Nicolausian discounting, i.e. ignoring small probabilities.

Bob Fischer @ 2025-11-24T10:42 (+4)

Thanks, Michael. I'm quite sympathetic to the idea of bracketing!

Denkenberger🔸 @ 2025-11-29T01:54 (+12)

Some say (slight hyperbole), "Teaching a child to not step on bugs is as valuable to the child as it is to the bug." So I think there is some mainstream caring about bugs.

JessMasterson @ 2025-12-09T09:32 (+3)

Perhaps, but I suspect they care a lot more about building empathy and compassion in children than they do about the actual well-being of bugs - I'd imagine that avoiding stepping on them is more of a means to an (anthropocentric) end.

Toby Tremlett🔹 @ 2026-02-12T11:01 (+6)

I’m curating this post.

It's a fairly simple observation (captured in the title — nice), but worth sharing.

It reminds me a little bit of Four Ideas You Already Agree With in that it chips away at the weirdness or uniqueness of EA ideas. This can feel disappointing — we all like to be unique — but ultimately it’s great, it means we have more allies.

JessMasterson @ 2025-12-09T09:39 (+6)

Great post - I'm on board with what you're saying.

You mention that entomologists would, if given the choice between "an aversive and a non-aversive way of euthanizing insects," prefer the latter. I feel like this is what we would expect, but I just wonder how far that goes. How much would the average entomologist be willing to inconvenience themselves to choose the non-aversive way? If both options required equal resources, effort, time etc, we should expect people to choose to minimise (questionable) suffering, but minimising suffering may not always require equal resources; it may require more. This is the case in plenty of situations of course, not just those involving bugs. Your post just made me wonder how committed the entomologists you've spoken to would be to choosing the non-aversive way.

Bob Fischer @ 2025-12-09T12:50 (+3)

Thanks, Jess. And great question. This is a little difficult to assess because of standard assumptions in the discipline. For instance, the lore is that the most humane way to both anesthetize and euthanize bugs is to throw them in the freezer, even though invertebrate veterinarians question this. As it happens, that's also the most convenient thing to do. So, we don't have a situation where there is agreement that some alternative would be better for the bugs, but people do the suboptimal thing regardless. Likewise, when people choose to do live dissections and other highly aversive procedures, they often say that they have to do it because a reviewer is going to insist on it (because that's the way it's been done before and so live dissection is critical to getting comparable data or whatever). So people don't conceive of themselves as having options where they really can choose a more humane alternative.

In any case, you are right to suggest that the average entomologist is not willing to take on huge inconveniences to do non-aversive work. But I do think an increasing number of them, particularly the under-40 crowd, are willing to take on some inconvenience, as shown by their interest in humane endpoints, reducing bycatch, learning about better husbandry options, etc.

JessMasterson @ 2025-12-10T16:57 (+1)

Thanks for the reply, Bob - it's great to learn more about this. It seems that so much just comes down to the available options. If freezing bugs feels like the only available option, it's totally understandable that people would do that. Without a clear consensus on what the best course of action is, people would probably rather do something than nothing. As for the live dissection thing, I suppose it highlights the complexity of making procedural changes in a scientific field.

Yaqi Grover @ 2025-11-24T16:59 (+6)

I wonder whether there are some lower-hanging-fruit interventions for insects that we could start pursuing now, rather than waiting until we have fully systematic approaches. In our effectiveness-minded space, we tend to focus on large, systematic interventions that can shift the biggest numbers and affect a large share of the animals under consideration. And I agree with the point here that there are still huge uncertainties, especially when it comes to wild insect populations where we’re extremely clueless, so it makes sense to hold off on anything too drastic.

But even with that uncertainty, there may still be neglected, practical opportunities that are small in percentage terms yet still affect enormous numbers of animals.

For example, in the US, there are live insects sold as reptile feed. I’ve heard estimates from a major supplier that roughly 100 million live crickets are sold each week – about 5 billion per year. And “pre-feed” mortality might be extremely high, possibly upward of 90 percent.

This represents only a tiny fraction of total farmed or wild insects, of course. But given that it still involves billions of animals, could targeted interventions here be worth pursuing anyway?

Vasco Grilo🔸 @ 2025-11-27T09:25 (+2)

Thanks for the suggestion, Yaqi! @vicky_cox, has Ambitious Impact (AIM) considered it? If not, you may want to add it to a list of potential ideas to look into.

vicky_cox @ 2025-11-27T21:30 (+3)

We have not considered it. I have added it to our scratchpad.

Vasco Grilo🔸 @ 2025-11-27T21:46 (+2)

Thanks, Vicky!

CB🔸 @ 2025-11-24T08:17 (+4)

Great post ! This makes sense.

Vasco Grilo🔸 @ 2025-11-23T16:55 (+3)

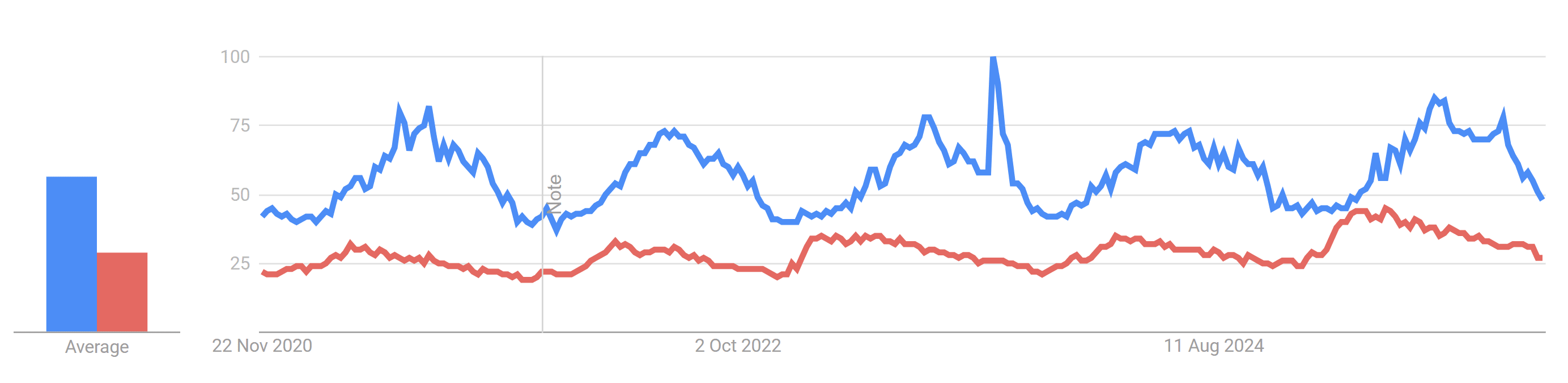

Agreed, Bob! As some evidence for interest in bugs not being weird, the number of posts on Instagram tagged as #bugs and #chickens is roughly the same.

Tristan Katz @ 2025-11-27T11:01 (+3)

I hope I'm not taking this too seriously, but the examples Bob gave are of looking with concern for the bugs' welfare. Entomologists presumably do that more than your average Instagram user because they actually study and handle the bugs. Others might just look at photos of bugs the same way they look at photos of plants or landscapes.

Vasco Grilo🔸 @ 2025-11-27T21:25 (+2)

Thanks, Tristan. I have now replaced "evidence for bugs not being weird" with "evidence for interest in bugs not being weird", which is what I meant (in agreement with my subsequent comment about Google Trends).

Vasco Grilo🔸 @ 2025-11-27T12:01 (+1)

Google Trends also reports more interest in bugs than chickens over the last 5 years.